Subjects Inside: Article

V Applications

FAQ,

Application Counts By

Congress, Articles,

AVC Legislative Report, CRS Reports,

Convention of State, Compact for America, COS, CFA--Which States are Which?, The Historic Record of COS, COS, CFA Laws, COS Articles, CRS Reports on COS/CFA, COS, CFA Financial Records, CFA Financials, COS Financials, COS/CFA Financial Conclusions, John

Birch Society, Con-Con, Runaway

Convention, Who Called the Convention, Congressional

Vote on a "Runaway" Convention, "Obey

the Constitution, Only Two More States", Illegal Rescissions, The Phony Burger Letter, The

Madison Letter, Fotheringham Exchange, JBS Articles, Sibley

Lawsuit, General Interest, Article V.org,

Robert Natelson, History

of Article V, Counting the Applications, The Numeric Count History, Congressional Decision of May 5, 1789,

Development of Article V, The Committee of the Whole, The Committee of Detail, August 30, September 10, Committee of Style, September 15, Official Government Documents,

History of FOAVC, Founders,

Audio/Visual,

Links,

Contact

Us, Legal

Page, 14th Amendment, The Electoral Process, Packets,

Definitions,

Numeric, (

Applications grouped by numeric count as required by the Constitution),

Same Subject (Applications grouped by amendment subject, not required by the Constitution for a convention call).

Page 6 B--Who Called the Convention, Congressional Vote on A "Runaway" Convention

Who Called the Federal Convention of 1787?

The Federal Convention

of 1787 met in Philadelphia

from May 25, 1787 to September 17, 1787 during which time it wrote the

proposed Constitution. As discussed

elsewhere on this site the proposal Constitution (including Article

V) underwent numerous revisions and drafts. On

Monday, September 17, 1787, the Federal Convention of 1787 concluded

its work and sent the engrossed proposed Constitution to Congress which

was meeting

in New York.

The proposed constitution was published in the Journals of

the Continental

Congress on Thursday, September 20, 1787. Formal debate on whether to

agree the

recommendation of the Federal Convention of 1787 began on September 27,

1787. Copies of all records found in the Journal of Congress

can be examined on our website.

In the discussion below copies of records either from the Journal of

Congress or pages from "The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787"

by Max Farrand are presented. For reading purposes the images may be

enlarged by clicking on the appropriate page image.

Robert Natelson, (See: Page 10), has stated the

state of Virginia "called" the Federal Convention

of

1787 rather than Congress. Natelson further

asserts

Congress accepted expansion of convention authority by passage of an

April 23,

1787

resolution granting franking privileges to the convention. He asserts

this action proves

Congress accepted expansion in authority for the Federal

Convention of 1787 beyond "merely proposing amendments to the Articles

of Confederation." (Natelson provides an erroneous link to a page of

the Journal

of Congress in his article discussing the resolution. The correct page

is shown at left, click to enlarge).

Nothing in the April 23, 1787 resolution supports Natelson's assertion

as

fact. There is no discussion by Congress that day indicating what

convention

power is expanded with franking privileges nor an explanation of how

granting franking privilege

expands convention power. Based on the published public record FOAVC

instead

believes the

franking resolution was no more than a budgetary procedure by Congress.

Public record shows neither

Congress or any state advanced any operational funds to the

convention prior to its convening in May, 1787.

Robert Natelson, (See: Page 10), has stated the

state of Virginia "called" the Federal Convention

of

1787 rather than Congress. Natelson further

asserts

Congress accepted expansion of convention authority by passage of an

April 23,

1787

resolution granting franking privileges to the convention. He asserts

this action proves

Congress accepted expansion in authority for the Federal

Convention of 1787 beyond "merely proposing amendments to the Articles

of Confederation." (Natelson provides an erroneous link to a page of

the Journal

of Congress in his article discussing the resolution. The correct page

is shown at left, click to enlarge).

Nothing in the April 23, 1787 resolution supports Natelson's assertion

as

fact. There is no discussion by Congress that day indicating what

convention

power is expanded with franking privileges nor an explanation of how

granting franking privilege

expands convention power. Based on the published public record FOAVC

instead

believes the

franking resolution was no more than a budgetary procedure by Congress.

Public record shows neither

Congress or any state advanced any operational funds to the

convention prior to its convening in May, 1787.

There is no record of

any funds received during the convention for its operational expenses.

Instead the convention

kept a tally of its expenses and forwarded these for reimbursement at

the

conclusion of the convention. This meant delegates and convention alike

were dependent on their own resources and the good graces of local

business given the dubious credit of the national government (one of

the reasons for holding the convention). Granting franking privileges

was merely a means to keep costs down.

As discussed elsewhere on this site

there

is a difference between the words "alter" and "amend." Moreover

Congress had already expanded the powers of the Federal Convention of

1787 beyond the limited word "amend" using the broader word

"revise" to describe the task assigned the convention. Having done so,

it had

no reason to revisit the issue when discussing franking privilege. Natelson

makes the same mistake in

wordage as JBS/Eagle Forum; there was no power to "amend" the Articles

of Confederation.

Further historic record proves Natelson wrong on who "called" the

convention. If, as Natelson

presumes, Congress did not call

the

Federal Convention of 1787, then the Annapolis

Convention of 1786 did so by setting a time and place for the

convention. According to historic records,

that convention of 12 men representing five states met in a tavern in

Annapolis, Maryland at the suggestion of James

Madison. The announced purpose of the convention was to discuss issues

of interstate trade. The convention determined it lacked sufficient

membership to make any recommendations but did request Congress call a

general convention for the following year (See image right, click to enlarge).

Further historic record proves Natelson wrong on who "called" the

convention. If, as Natelson

presumes, Congress did not call

the

Federal Convention of 1787, then the Annapolis

Convention of 1786 did so by setting a time and place for the

convention. According to historic records,

that convention of 12 men representing five states met in a tavern in

Annapolis, Maryland at the suggestion of James

Madison. The announced purpose of the convention was to discuss issues

of interstate trade. The convention determined it lacked sufficient

membership to make any recommendations but did request Congress call a

general convention for the following year (See image right, click to enlarge).

As the convention in

its 1786 report to Congress (See Page 12 Table 2) clearly understood it lacked authority

to call a national

convention Natelson in 2016 correctly states the Annapolis Convention

did not have

authority to

call a national convention. Instead Natelson insists the

state of Virginia had authority to call a national convention.

Apparently, according to Natelson, than for no other reason

than in response to the "call" by the Annapolis its legislature was the

first to echo the "call" by passage of a resolution. Natelson

provides no legal citation from the Articles of Confederation or

Virginia state law of that time granting the state of Virginia

authority to call a

national

convention.

However, as recognized by the Annapolis Convention, the

Articles of Confederation did give Congress

authority to call a convention. Article XIII states, "Every State shall

abide by the determination of the United States in Congress

assembled, on all questions which by this confederation are

submitted to them." The question of calling a convention for the

express purpose of "revising" the Articles of Confederation was put

before Congress by the report of the Annapolis Convention

commissioners. Under the terms of the Articles of Confederation the

decision of Congress to call the Federal Convention of 1787 was

authorized

under the national law of that time and was expressly removed from all

states. Therefore plainly the state of Virginia did not have authority

to decide the "question" of a

convention call. Congress clearly did. Congress used this authority to

issue the actual convention call on February 21, 1787 and thus was the

body that "called" the Federal Convention of 1787.

Any

lingering doubt as to who had

authority to call the convention is resolved by answer to the two most

pragmatic questions about the convention--who funded the Federal

Convention of 1787 and to whom did the convention report? Obviously,

if, as Natelson contends, the state of

Virgina, (or some other state), actually called the convention then

reasonably those responsible for the convention call would bear

the cost of holding it. This was not the case. Together with the

proposed

Constitution and other paperwork the Federal Convention of 1787

submitted a

bill to Congress for $1163.90 for convention expenses consisting of

wages,

supplies and printing. In today's dollars, the cost of the

Federal Convention of 1787 was approximately $30,000 of which its

secretary William Jackson was paid approximately $22,000 for

four months work.

Any

lingering doubt as to who had

authority to call the convention is resolved by answer to the two most

pragmatic questions about the convention--who funded the Federal

Convention of 1787 and to whom did the convention report? Obviously,

if, as Natelson contends, the state of

Virgina, (or some other state), actually called the convention then

reasonably those responsible for the convention call would bear

the cost of holding it. This was not the case. Together with the

proposed

Constitution and other paperwork the Federal Convention of 1787

submitted a

bill to Congress for $1163.90 for convention expenses consisting of

wages,

supplies and printing. In today's dollars, the cost of the

Federal Convention of 1787 was approximately $30,000 of which its

secretary William Jackson was paid approximately $22,000 for

four months work.

Further the

convention correspondence sent directly to Congress contained a

specific letter of request by convention

president, George

Washington, that

Congress consider

the proposal of the convention. Had the convention

believed it had authority of amendment as JBS/Eagle Forum contend

instead of a recommendation that Congress consider its proposal, the Federal Convention of 1787 would have informed Congress of its decision. Had a state,

such as Virginia, been responsible for the call, obviously all

correspondence from the convention would have been directed to that state and that state would have either been

"informed" or requested to "consider" the recommendation of the

convention.

The "consideration" of something includes the

possibility of rejection or

modification. The use of the word by the convention means its delegates

realized Congress

could reject their proposal, modify it or transmit it as written to the

states. Thus, whatever Congress, not

the Federal Convention of 1787 decided, would be the proposal

considered by the states as the "question" of what to propose to

resolve the "exigencies of Government and preservation of the Union." Thus, according to public record and acknowledged by the

Federal Convention of 1787, Congress, not the

convention, decided whether to propose the new Constitution,

determined the final version of that proposal (unaltered from that

proposed by the convention) and established under what

terms that proposal would be considered by the states. This is a far

cry

from the utterly wrong version of history set forth

by JBS/Eagle

Forum as its basis to oppose an Article V Convention.

Further the

convention correspondence sent directly to Congress contained a

specific letter of request by convention

president, George

Washington, that

Congress consider

the proposal of the convention. Had the convention

believed it had authority of amendment as JBS/Eagle Forum contend

instead of a recommendation that Congress consider its proposal, the Federal Convention of 1787 would have informed Congress of its decision. Had a state,

such as Virginia, been responsible for the call, obviously all

correspondence from the convention would have been directed to that state and that state would have either been

"informed" or requested to "consider" the recommendation of the

convention.

The "consideration" of something includes the

possibility of rejection or

modification. The use of the word by the convention means its delegates

realized Congress

could reject their proposal, modify it or transmit it as written to the

states. Thus, whatever Congress, not

the Federal Convention of 1787 decided, would be the proposal

considered by the states as the "question" of what to propose to

resolve the "exigencies of Government and preservation of the Union." Thus, according to public record and acknowledged by the

Federal Convention of 1787, Congress, not the

convention, decided whether to propose the new Constitution,

determined the final version of that proposal (unaltered from that

proposed by the convention) and established under what

terms that proposal would be considered by the states. This is a far

cry

from the utterly wrong version of history set forth

by JBS/Eagle

Forum as its basis to oppose an Article V Convention.

The Debate In Congress; The Vote on a "Runaway" Convention

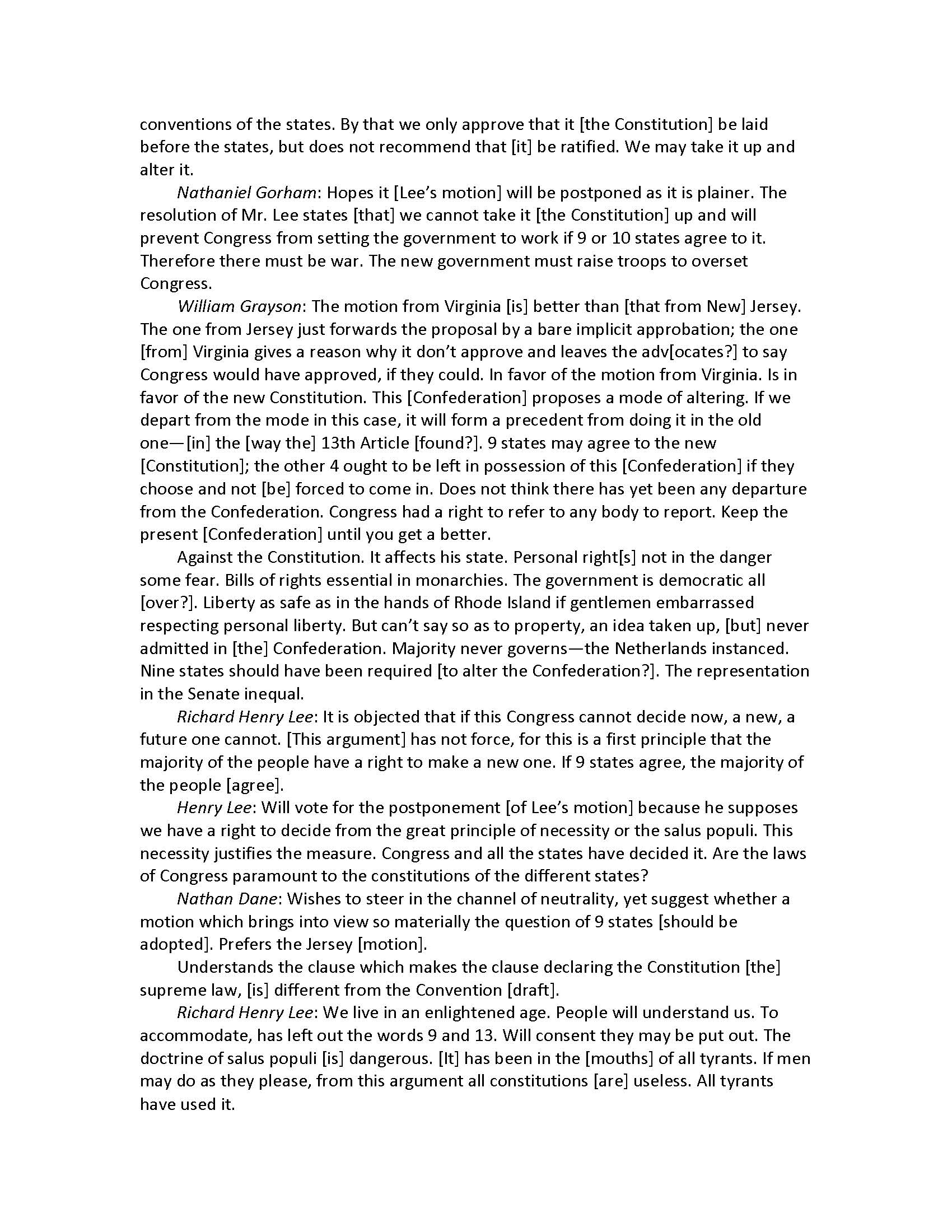

Debate in Congress over the proposed Constitution began on Thursday,

September 27, 1787 ten days after the convention had adjourned. The

proposed Constitution and all other associated documentation from the

Federal Convention of 1787 was published in full in

the Journal of Congress on

September 20, 1787. The week gave members of Congress ample time to

study the proposal and to take positions regarding it. The

Journal of Congress did not, as is the custom today, recount all words

spoken in Congress verbatim.

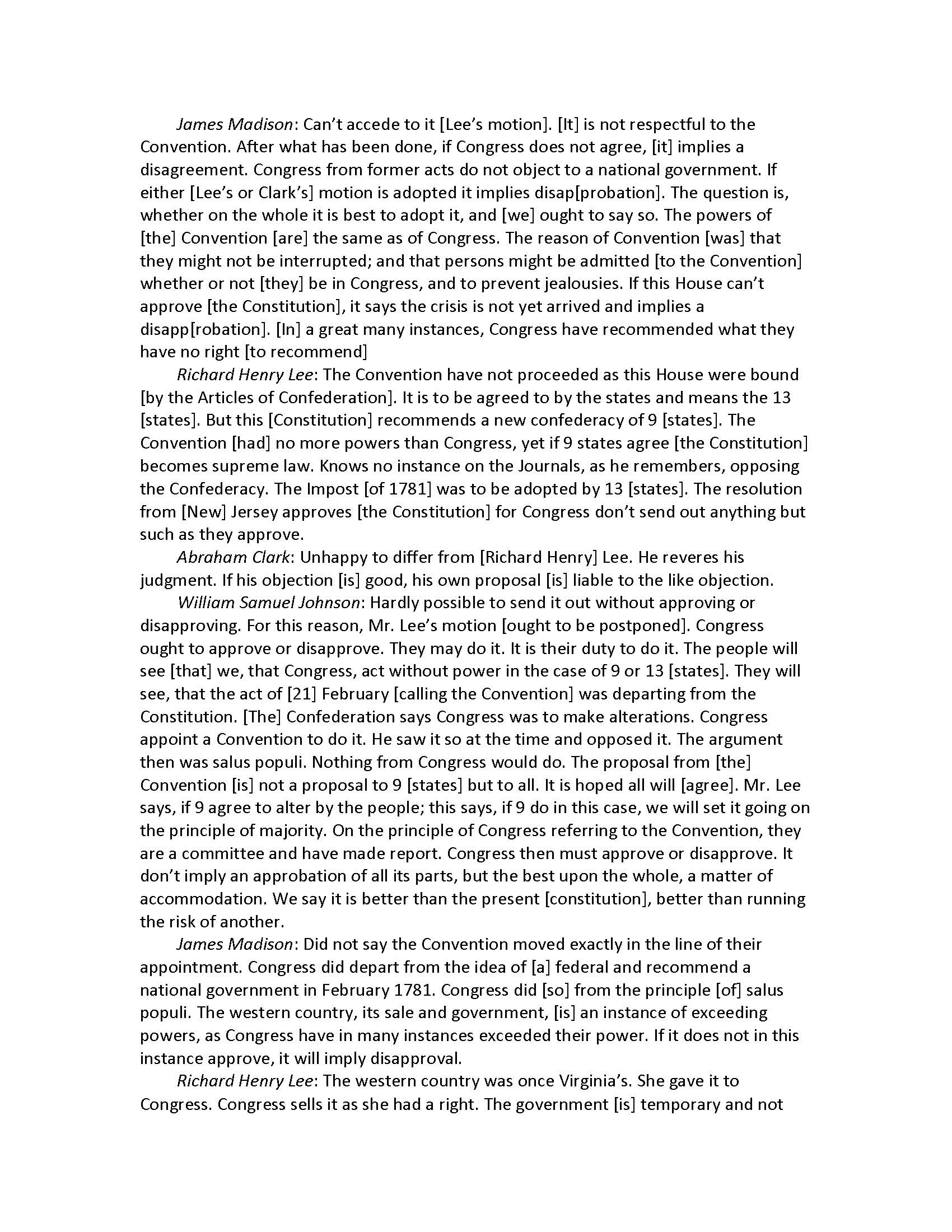

Fortunately Melancton Smith, a member of

the New York delegation, took detailed notes of the comments made

during

the debate (reprinted below; click to enlarge). The

debate centered on two points with opposition to the proposal lead by

Richard Henry Lee of Virginia. First, whether Congress

would exceed its

authority in proposing the new Constitution (and thus agree the

convention that proposed it was a "runaway" as alleged by JBS/Eagle

Forum). Second, whether Congress had

authority to alter the proposed Constitution before submitting it to

the states.

The Melancton Notes

Lee,

Clarke, Carrington, Dane and Final Resolution By Congress

In all, four

resolutions were debated in Congress on September 27, 1787. Ultimately

none were accepted by Congress.

The first resolution by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, (seconded by

Melancton Smith of New York) read: "Resolved

That Congress after due attention to the Constitution under which this

body exists and acts find that the said Constitution in the thirteenth

Article thereof limits the power of Congress to the amendment of the

present confederacy of thirteen states, but does not extend it to the

creation of a new confederacy of nine states; and the late Convention

having been constituted under the authority of twelve states in this

Union it is deemed respectful to transmit and it is accordingly ordered

that the plan of a new federal constitution laid before Congress by the

said convention be sent to the executive of every state in this union

to be laid before their respective legislatures."

By a vote of 26-5 Congress rejected

Lee's "runaway" convention

resolution. Logically, if Congress did not have power to "extend...to

the creation of new confederacy" any convention it called did not have

authority to propose it. Therefore any such convention would have

exceeded its "scope" and therefore was a "runaway" convention. As

Congress voted down Lee's resolution it also resolved the question of

whether the Federal Convention of 1787 was a "runaway" and officially determined the

convention was not

a "runaway" convention. Congress had authority to decide this question

under the authority granted it by the Articles of Confederation.

Having officially disposed of the "runaway" convention theory of Lee's

(and therefore JBS/Eagle Forum),

Congress considered three other proposals each favoring submission

of the proposed Constitution to the states but under different

circumstances. Each in turn was "postponed" in favor of the next

proposal. In the end no proposal was affirmed by Congress on September

27, 1787.

The second resolution of September 27, 1787 by Abraham Clarke of New

Jersey (seconded by

Nathaniel Mitchell of Delaware) reads: "That a copy of the Constitution

agreed to and laid before Congress by the late Convention of the

several states with their resolutions and the letter accompanying the

same be transmitted to the executives of each state to be laid before

their respective legislatures in order to be by them submitted to

conventions of delegates to be chosen agreeably to the said resolutions

of the Convention."

The third resolution by Edward Carrington of of Virginia (seconded by

William Bingham of Pennsylvania) read, "Congress proceeded to the

consideration of the Constitution for the United States by the late

Convention held in the City of Philadelphia and thereupon resolved That

Congress do agree thereto and that it be recommended to the

legislatures of the several states to cause conventions to be held as

speedily as may be to the end that the same may be adopted ratified and

confirmed."

A fourth resolution was made by Nathan Dane of Massachusetts with no

record of a second in Journal of Congress and is shown in the

fourth and fifth panels above. As there was no recorded second it is

unclear whether

this resolution was actually considered by Congress as it appears not

to

have been properly introduced on the floor. In any event it was not

transmitted to the states.

On September 28, 1787 Congress unanimously passed a fifth resolution: "Resolved Unanimously

that the said Report with the resolutions and letter accompanying

the same be transmitted to the several legislatures in Order to be

submitted to a convention of Delegates chosen in each state by the

people thereof in conformity to the resolves of the Convention made and

provided in that case."

There is no record of what events occurred

among

members of Congress after the four resolutions of September 27, 1787

were introduced and voted on and defeated. There is no

record who wrote the final resolution, who seconded it or why it was

"unanimously" approved apparently

without debate by Congress though it appears to be based on the Clarke

resolution. However the final vote was arrived at, the

language is conclusive. Congress

officially (and unanimously) agreed in all aspects with the

recommendations of the

Federal Convention of 1787 and forwarded those recommendations to the

states for their consideration. Unlike the previous four motions, all

of which failed, the final language clearly

shows agreement on the part of Congress with the proposed Constitution

and its method of ratification thus satisfying the term "agreed"

expressed in the Articles of Confederation.

This vote is conclusive as to the question of

whether

the Federal Convention of 1787 was a "runaway" convention as

characterized by JBS/Eagle Forum. If

Congress believed the convention exceeded the authority granted it

in the

February 21, 1787 call, Congress ultimately would have accepted Lee's

resolution. There was a recorded vote which clearly shows Congress

rejected the notion the Federal Convention of 1787 was a "runaway"

convention. Thus, by official vote of Congress, as empowered by the

Articles of Confederation to determine such questions Congress

officially considered the question whether the Federal Convention of

1787 was a "runaway" convention and officially determined it was not.

If Congress believed Congress lacked authority in regards to proposing

the

Constitution then clearly Dane's resolution would have been accepted.

However, in both cases Congress rejected these in favor of unanimously

accepting the recommendations of the convention (and its proposed

ratification mode) and ordered that the proposed Constitution be first

sent to the state legislatures and then to conventions representative

of the people. This is exactly what occurred. Thus the states

accepted

the authority of Congress to propose the Constitution, establish the

terms and conditions for its consideration and, by obvious implication,

accepted the Federal Convention of 1787 was within its "scope" to

propose the new Constitution. All of this was in accordance with the

authority granted Congress in the Articles of Confederation.

Besides the legal effect of the

binding clause in the Articles of Confederation, the pragmatic fact was

those members of Congress deciding this question were the same members

of Congress who issued the convention call on February 21, 1787. Thus

these members fully understood what their

resolution meant, its intent and what authority it conferred on the

Federal Convention of 1787. Additionally, the convention, having

adjourned only ten days before, all participants were alive and in full

possession of

their faculties. Many of the convention delegates served in Congress

and had returned in time to participate in the September

27, 1787 debate. Thus first hand knowledge was available to all members

of Congress.

The specific question of "scope" was answered by Congress

with a 26-5 vote in favor of the convention. The ultimate response to

the JBS/Eagle Forum allegation of a "runaway" convention was an

official,

unanimous vote by Congress which included the five dissenters who

believed the convention proposal to be beyond its "scope." Thus the

official vote by Congress addressing the question of a "runaway"

convention done by the persons in the best position to make such a

determination proves the

JBS/Eagle Forum allegation of a "runaway" convention entirely false. As

such a vote occurred in the first person by those directly involved in

the events, their determination must be viewed as absolutely conclusive

on the subject.

These facts of public record are

ignored by JBS/Eagle Forum who contend it is "clear

... what happened in 1787 when the Constitution

was written." The best that can be said for this "clear" view by

JBS/Eagle Forum is its "clear" view of events in 1787 is wrong. To

arrive at their "clear" view JBS/Eagle Forum ignore relevant facts of

public record including the public law of 1787.

Allegations by JBS/Eagle the Federal

Convention of 1787 exceeded its authority by proposing the Constitution

and was therefore

a "runaway" convention are false. Allegation the Federal Convention

of 1787 had authority to "amend" the Articles of Confederation are

false. There is nothing in the public record, nor has JBS/Eagle Forum

ever presented evidence proving that based

on public record of the time, the

Constitution was anything but legally

ratified

under the terms of national law of the time.

As the Federal Convention

of 1787 was not a "runaway" convention but held strictly in compliance

with the law of the time, there is no basis to assert an Article V

Convention held today would be a "runaway" as there was no "runaway"

convention in the first place.

Page Last Updated: 9-APRIL 2017

Robert Natelson, (See: Page 10), has stated the

state of Virginia "called" the Federal Convention

of

1787 rather than Congress. Natelson further

asserts

Congress accepted expansion of convention authority by passage of an

April 23,

1787

resolution granting franking privileges to the convention. He asserts

this action proves

Congress accepted expansion in authority for the Federal

Convention of 1787 beyond "merely proposing amendments to the Articles

of Confederation." (Natelson provides an erroneous link to a page of

the Journal

of Congress in his article discussing the resolution. The correct page

is shown at left, click to enlarge).

Robert Natelson, (See: Page 10), has stated the

state of Virginia "called" the Federal Convention

of

1787 rather than Congress. Natelson further

asserts

Congress accepted expansion of convention authority by passage of an

April 23,

1787

resolution granting franking privileges to the convention. He asserts

this action proves

Congress accepted expansion in authority for the Federal

Convention of 1787 beyond "merely proposing amendments to the Articles

of Confederation." (Natelson provides an erroneous link to a page of

the Journal

of Congress in his article discussing the resolution. The correct page

is shown at left, click to enlarge). Further historic record proves Natelson wrong on who "called" the

convention. If, as Natelson

presumes, Congress did not call

the

Federal Convention of 1787, then the Annapolis

Convention of 1786 did so by setting a time and place for the

convention. According to historic records,

that convention of 12 men representing five states met in a tavern in

Annapolis, Maryland at the suggestion of James

Madison. The announced purpose of the convention was to discuss issues

of interstate trade. The convention determined it lacked sufficient

membership to make any recommendations but did request Congress call a

general convention for the following year (See image right, click to enlarge).

Further historic record proves Natelson wrong on who "called" the

convention. If, as Natelson

presumes, Congress did not call

the

Federal Convention of 1787, then the Annapolis

Convention of 1786 did so by setting a time and place for the

convention. According to historic records,

that convention of 12 men representing five states met in a tavern in

Annapolis, Maryland at the suggestion of James

Madison. The announced purpose of the convention was to discuss issues

of interstate trade. The convention determined it lacked sufficient

membership to make any recommendations but did request Congress call a

general convention for the following year (See image right, click to enlarge).  Any

lingering doubt as to who had

authority to call the convention is resolved by answer to the two most

pragmatic questions about the convention--who funded the Federal

Convention of 1787 and to whom did the convention report? Obviously,

if, as Natelson contends, the state of

Virgina, (or some other state), actually called the convention then

reasonably those responsible for the convention call would bear

the cost of holding it. This was not the case. Together with the

proposed

Constitution and other paperwork the Federal Convention of 1787

submitted a

bill to Congress for $1163.90 for convention expenses consisting of

wages,

supplies and printing. In today's dollars, the cost of the

Federal Convention of 1787 was approximately $30,000 of which its

secretary William Jackson was paid approximately $22,000 for

four months work.

Any

lingering doubt as to who had

authority to call the convention is resolved by answer to the two most

pragmatic questions about the convention--who funded the Federal

Convention of 1787 and to whom did the convention report? Obviously,

if, as Natelson contends, the state of

Virgina, (or some other state), actually called the convention then

reasonably those responsible for the convention call would bear

the cost of holding it. This was not the case. Together with the

proposed

Constitution and other paperwork the Federal Convention of 1787

submitted a

bill to Congress for $1163.90 for convention expenses consisting of

wages,

supplies and printing. In today's dollars, the cost of the

Federal Convention of 1787 was approximately $30,000 of which its

secretary William Jackson was paid approximately $22,000 for

four months work.

Further the

convention correspondence sent directly to Congress contained a

specific letter of request by convention

president, George

Washington, that

Congress consider

the proposal of the convention. Had the convention

believed it had authority of amendment as JBS/Eagle Forum contend

instead of a recommendation that Congress consider its proposal, the Federal Convention of 1787 would have informed Congress of its decision. Had a state,

such as Virginia, been responsible for the call, obviously all

correspondence from the convention would have been directed to that state and that state would have either been

"informed" or requested to "consider" the recommendation of the

convention.

Further the

convention correspondence sent directly to Congress contained a

specific letter of request by convention

president, George

Washington, that

Congress consider

the proposal of the convention. Had the convention

believed it had authority of amendment as JBS/Eagle Forum contend

instead of a recommendation that Congress consider its proposal, the Federal Convention of 1787 would have informed Congress of its decision. Had a state,

such as Virginia, been responsible for the call, obviously all

correspondence from the convention would have been directed to that state and that state would have either been

"informed" or requested to "consider" the recommendation of the

convention.