The public record of applications however shows that, in fact, 15 states have submitted "Convention of States" applications to Congress over the years. For apparent undisclosed political reasons, the convention of states organization has chosen only to recognize 12 of these applications.

COS uses the "traditional" amendment process of gathering "same subject" applications (despite the fact the Constitution has no such requirement); CFA uses an untested legal theory attempting to circumvent the Article V amendment process. Thus, politically, once a state "joins" COS or CFA it cannot "join" the other group. However the questions of legality and constitutionally also apply when determining which states support which organization. As a compact (a form of contract established for states in the Constitution) is involved it is possible once a state "joins" CFA, they are excluded from "joining" COS by the terms of the compact. Four states, Alaska, Arizona, Georgia and North Dakota have "joined" both CFA and COS. As the compact precludes joining COS as the political agenda for the two organizations are entirely different, the question arises as to whether these four states are part of the COS or CFA tabulation of states.

Neither COS nor CFA have made any public effort to clarify this issue. However, until the matter is resolved the reported number of states supporting either COS and CFA is dubious. As a compact under the terms of the Constitution is a form of binding contract on the state thus superseding any resolution or legislative act to the contrary, it is likely those states joining the CFA compact, assuming the compact is constitutional which is dubious, must be counted as CFA, rather than COS, states. Thus the states of Alaska, Arizona, Georgia and North Dakota must be placed in the CFA column making the count of states eight states in the COS column and five states in the CFA column.

However the matter does not end there. There appears to be no consistent policy regarding what is, and what is not, a "convention of states" application. Convention of States Project has claimed some state applications as "convention of states" applications but has failed to acknowledge other state applications as "convention of states" applications. The question is: what is the policy which determines what is, and what is not, a "convention of states" application? The specific issues surrounding several state applications are discussed below.

The Alaska Application

In many cases COS has claimed applications which, while the state may use the term, "convention of states" somewhere in the application, is, in fact a "standard" Article V Convention application. In the case of the Alaska "COS" application, for example, the term "convention of states" is used in the opening paragraph, but the application requested subject matter (nullification of federal laws, regulations and court orders) not in the COS political agenda. It would appear then if the phrase "convention of states" is used in the application, the application is a "convention of states" application. However, other examples of state applications and claims by Convention of States refute this thus making a determination of what is, and what is not, a "convention of states" application dubious at best.

The Florida Application

In the case of the Florida application, while the application matches the political goals stated by COS, no where does the term "convention of states" appear in the application. This raises a question of validity of the claim by COS that 12 states have applied for a "convention of states." Have the states actually applied in support of the COS political agenda and thus this makes it a "convention of states" application or is COS simply claiming any application using the term "convention of states" as its own (regardless of application content and intent) in order to further its own political agenda? The answer appears to be both and neither.

The Arizona Application

On March 14, 2017 the state of Arizona passed House Concurrent Resolution 2010 "applying to the Congress of the United States to call a convention for proposing amendments to the Constitution of the United States." Because the resolution used the term "convention of states" in passing in the text of the resolution, COS immediately claimed it as one of their own. Yet the title of the application clearly describes a "convention for proposing amendments" rather than a "convention of states." It is the strict policy of FOAVC not to publish any application until it is officially received and recorded by Congress. Therefore the text of the application will not appear on our list of applications until it is recorded in the Congressional Record. Moreover the record available at the Arizona State Legislature website while noted to be "engrossed" fails to show any official signatures proving the text as shown is actually an official state document. This stated however, as FOAVC has raised the point regarding the text of the application and our policy is to provide evidence for our statements we are publishing the text of the application from the Arizona Legislature.

Other "Convention of States" Applications not acknowledged by Convention of States

As we have stated before "COS has failed to acknowledge an already submitted application by a state using the term "convention of states" in the text of the application and which politically reflects the COS agenda in the text of application in its "count" of COS applications. Applications submitted by the states of South Carolina, Wyoming and Michigan have not been recognized by Convention of States as "convention of states" applications yet all contain the term "convention of states" or reflect the political agenda of the group, Convention of States. As discussed above COS has claimed state applications as "Convention of States" applications in which either of these two conditions were satisfied or in which one of the two conditions were satisfied. Yet in these three cases COS has not claimed them as "Convention of States" applications despite the fact at least one of the two conditions apparently required to be consider a "Convention of States" application has been satisfied. Therefore there appears to be no consistency in how a state application is judged to be a "convention of states" application. The South Carolina application may be read here and here. The Wyoming application may be read here. The Michigan application may be read here.

The Texas and Missouri Applications

Meanwhile, COS claimed a Texas application which doesn't contain the phrase "convention of states" in its text, as a "convention of states" application but does reflect the political agenda of the group Convention of States. An application by the state of Missouri was claimed by COS as a "convention of states" application contained the phrase "convention of states" and the political agenda of the Convention of States Project.

Conclusion Regarding Convention of States Applications

The only conclusion possible, based on the record of state applications and response by the Convention of States Project is COS cherry picks which state applications are "convention of states" applications and which state applications are not "convention of states" applications. The basis of the choice appears to be political, rather than constitutional. The Convention of States Project apparently has no consistent policy describing what is, and what is not a "convention of states" application. Thus, any "count" of state applications purporting to be "convention of states" applications is entirely arbitrary and unreliable.

The COS Applications and the question of an "open" or "closed" convention

The political organization Convention of States advocates a particular political agenda which COS steadfastly states will be the only political agenda considered at a "convention of states" convention. This kind of a politically restricted convention is generally referred to as a "closed" convention (also known as a "limited" convention). (See: Page 11 A; Page 11 D). However, if the political group "Convention of States" incorporates any state application containing any political agenda which just happens to use the term "convention of states" regardless of the political subject within the application in order to achieve its "count" of applications then that is a version of what is known as an "open" convention. An example of this is the Alaska application above which refers to a "convention of states" application but whose subject matter is completely different than the subject matter of COS.

The "convention of states" then becomes an "open" convention. This means all applications containing any political subject ever submitted by the states are considered by the convention in its agenda. The only difference then between a "convention for proposing amendments" (the term used in Article V) and a "convention of states" is simply another term for an Article V Convention or "convention for proposing amendments." The term "convention of states" then becomes meaningless except as a political slogan of a specific political group. The term is not used in the Constitution. Therefore not being used in the Constitution, the powers and terms associated with this title by this group (COS) has no actual affect on the powers of an Article V Convention. These powers (as described by the Founders, Supreme Court rulings and federal law is that the convention for proposing amendments may propose whatever amendments the elected delegates believe is appropriate. The term "convention for proposing amendments" carries clearly implies several political subjects of varying natures requiring several amendments can be considered and proposed by the convention.

However this not the case in a Convention of States convention. COS has made it clear that only its political agenda is to be considered at a "convention of states." It has sought and obtained passage of state laws designed to only advance the COS political agenda at a convention. These laws describe a certain kind of convention which does not allow participation of the American public through the elective process. The convention is limited strictly to control by the state legislatures and not the people. The only interpretation of COS actions in designating state applications which do not "match" the COS political agenda is the political group Convention of States is attempting to take political advantage of these applications by incorporating them in its "count" of applications with absolutely no intention of giving those applications any consideration whatsoever at any "convention of states" convention.

Delegate Section and Convention Agenda

Whether

a convention is "open" or closed" relates directly to the question of

delegate selection and convention agenda. In their well funded campaign

whose statements are apparently accepted

without question by supporter and opponent alike just like JBS/Eagle

Forum statements (See: Page 6), at no time does COS/CFA ever mention the American people are excluded

entirely from the convention process meaning the people have no part in

delegate

selection or in review of convention agenda. State laws enacted in several states remove

their right of "alter or abolish" described in the Declaration of

Independence (See: Page 5 B).

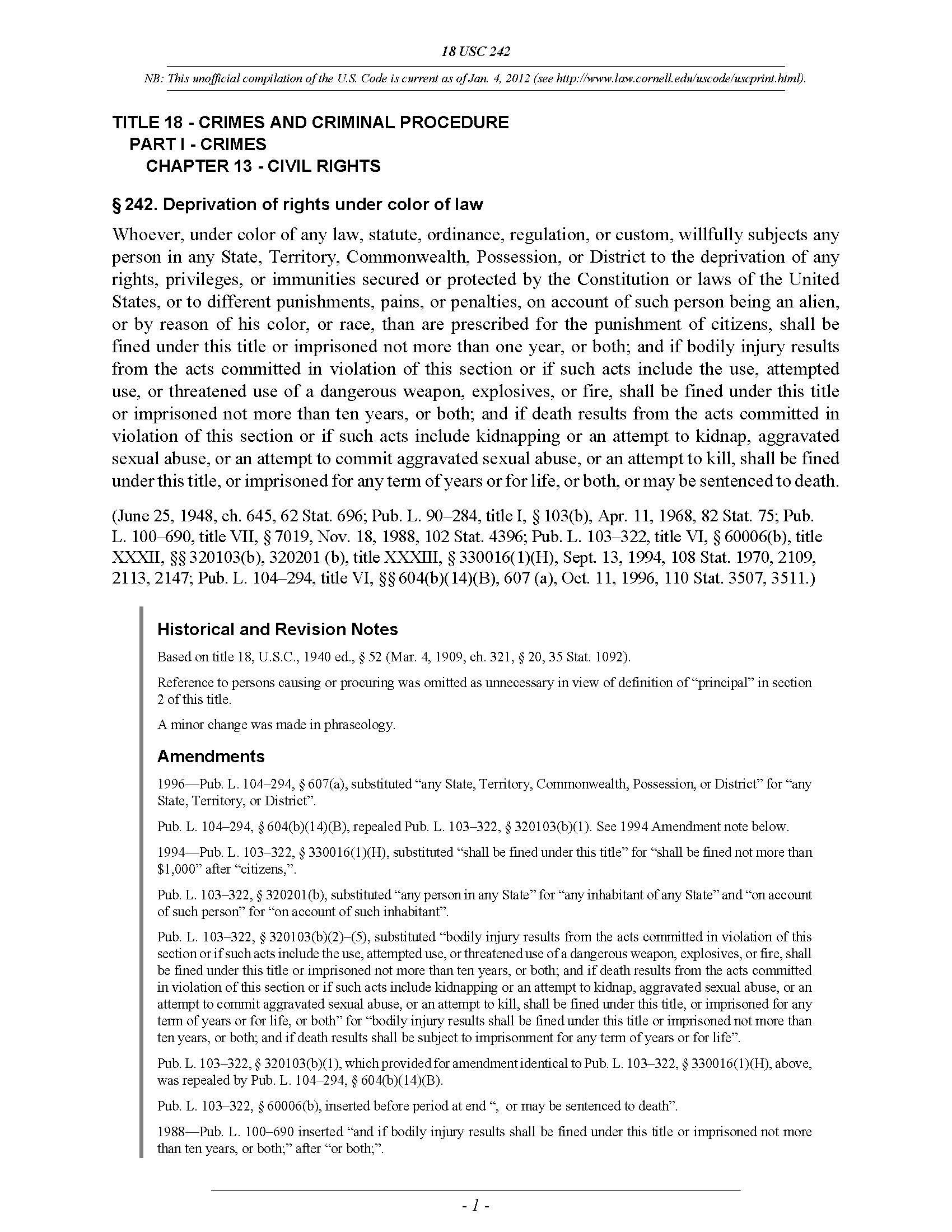

Such laws conflict with already existing federal criminal laws which

prohibit removal of the right to vote (18 U.S.C. 242) as well a

criminal law (18 U.S.C. 601) specifying convention delegates shall be elected (See images left, click to enlarge).

Whether

a convention is "open" or closed" relates directly to the question of

delegate selection and convention agenda. In their well funded campaign

whose statements are apparently accepted

without question by supporter and opponent alike just like JBS/Eagle

Forum statements (See: Page 6), at no time does COS/CFA ever mention the American people are excluded

entirely from the convention process meaning the people have no part in

delegate

selection or in review of convention agenda. State laws enacted in several states remove

their right of "alter or abolish" described in the Declaration of

Independence (See: Page 5 B).

Such laws conflict with already existing federal criminal laws which

prohibit removal of the right to vote (18 U.S.C. 242) as well a

criminal law (18 U.S.C. 601) specifying convention delegates shall be elected (See images left, click to enlarge). A COS/CFA convention denies the people their right to vote directly on the matters concerning a convention (such as who will decide on the fate of the American people). There is no guarantee that following a COS/CFA convention the right of the people to vote will remain intact as the people know it today. It is entirely reasonable to postulate a COS/CFA will remove this right based on already existing COS/CFA state laws.

As the 14th Amendment (See Page 18) requires equal protection under the law (See: Page 17 E) it is reasonable (and constitutional) to postulate all political bodies involved in the amendment process (Congress, state legislatures) who are inclined to extend power for themselves at the expense of the fundamental principles of this nation may take advantage of this removal of vote from the people.

If Congress and the state legislatures were to extend these already existing state laws to include themselves as well as convention delegates by extending the prohibition of voting include their governmental bodies this would mean the American people would have no say as to how long a member in Congress or a state legislature remained in power or what he was allowed to do while in power. The American people would have no ability to employ the primary means used to control politicians---removal from office. The problem is that removal of the right to vote for members of Congress and state legislators can be accomplished, not by amendment, but by legislation. Article I of the Constitution and the 17th Amendment specifies the qualification for electors choosing senators and representatives for Congress. (Senate: "The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State, elected by the people thereof, for six years; and each Senator shall have one vote. The electors in each State shall have the qualifications requisite for electors of the most numerous branch of the State legislatures." House: "The House of Representatives shall be composed of Members chosen every second Year by the People of the several States, and the Electors in each State shall have the Qualifications requisite for Electors of the most numerous Branch of the State Legislature.").

A change in qualification for elector at the state level in the lower house of a state legislature automatically affects qualification for election of of members of Congress. Under the COS state laws being enacted no one is qualified as an elector. Therefore no citizen may vote on the question of convention delegates. The same principle could be extended based on the same legal principle being advanced in the state laws to include members of Congress and state legislators as both bodies are part of the same amendment process and one portion of that process (convention delegates) are not elected none of the other bodies shall be elected because state law disqualifies all citizens as electors.

COS/CFA have both publicly favored the one state/one vote principle used by the Federal Convention of 1787. This means state delegates are gathered into state delegations which then vote as a collective group with each state delegation having one vote. (See: COS Proposed Rules, Rule 4; CFA Compact, Article VII, Section 4). The method allows each state (and thus the population within each state) equal voice as to any proposal which would equally effect all states, and thus all populations, equally.

In this instance, so far as the principle of one state/one vote is concerned FOAVC agrees with COS/CFA. FOAVC believes any convention held today, particularly in the light of the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment, must employ the one state/one vote method of voting in a convention. Any other method, such as voting by representative state populations (thus granting large states such as California more "voice" in a proposed amendment than a small state such as Nevada) denies the populations within each state, and thus the citizen comprising that population, equal voice (and thus equal protection) in a proposal which equally affects all states and populations.

States are equal because the citizens comprising these states are equal. Thus all states have equal rights. This includes the second right, the right of redress guaranteed the citizen (and thus the state) in the First Amendment. A convention is the constitutional means whereby citizens, acting through elected convention delegates voting as state delegations, seek redress of issues at the constitutional level. This First Amendment right of redress prohibits any particular political group (such as COS/CFA) from compromising that right by determining only a select portion of issues may be discussed or proposed at a convention. The right of redress guarantees all issues shall be presented and discussed at the convention. It further guarantees that no state may be denied its right to present whatever issue it desires at convention. Thus no application submitted by a state may be denied or ignored by the convention by a predetermined political agenda.

The states have submitted numerous issues in applications for an Article V Convention outside of those itemized COS/CFA "convention of states" applications. If the states are equal as COS/CFA recognizes with is "one state/one vote" endorsement, then it is impossible for COS/CFA to deny the states equal access to the convention such that only certain issues are permitted to be discussed at a convention (which happen to present the COS/CFA political agenda). FOAVC believes under the terms of the First and 14th amendments denial of equal right of redress and denial of equal protection is unconstitutional (See: Page_18). While FOAVC supports the one state/one vote method used in the 1787 Convention making all states (and thus state populations) equal, it also supports the equal redress demonstrated at that same convention. All states were able to discuss and propose whatever issues they chose. FOAVC opposes the COS/CFA concept of "one state/one vote/allowed only to present what COS/CFA instructs and politically wants" as FOAVC believes the concept is unconstitutional.