Having

received the report of the Committee of Style

and Arrangement on September 12, the Federal Convention of 1787 again

debated the various provisions of the revised text of the nearly

complete Constitution making numerous changes (See Page 12, Table 8). With

the convention only hours away from concluding its business on

Saturday, September 15 the convention "took up" the matter of the

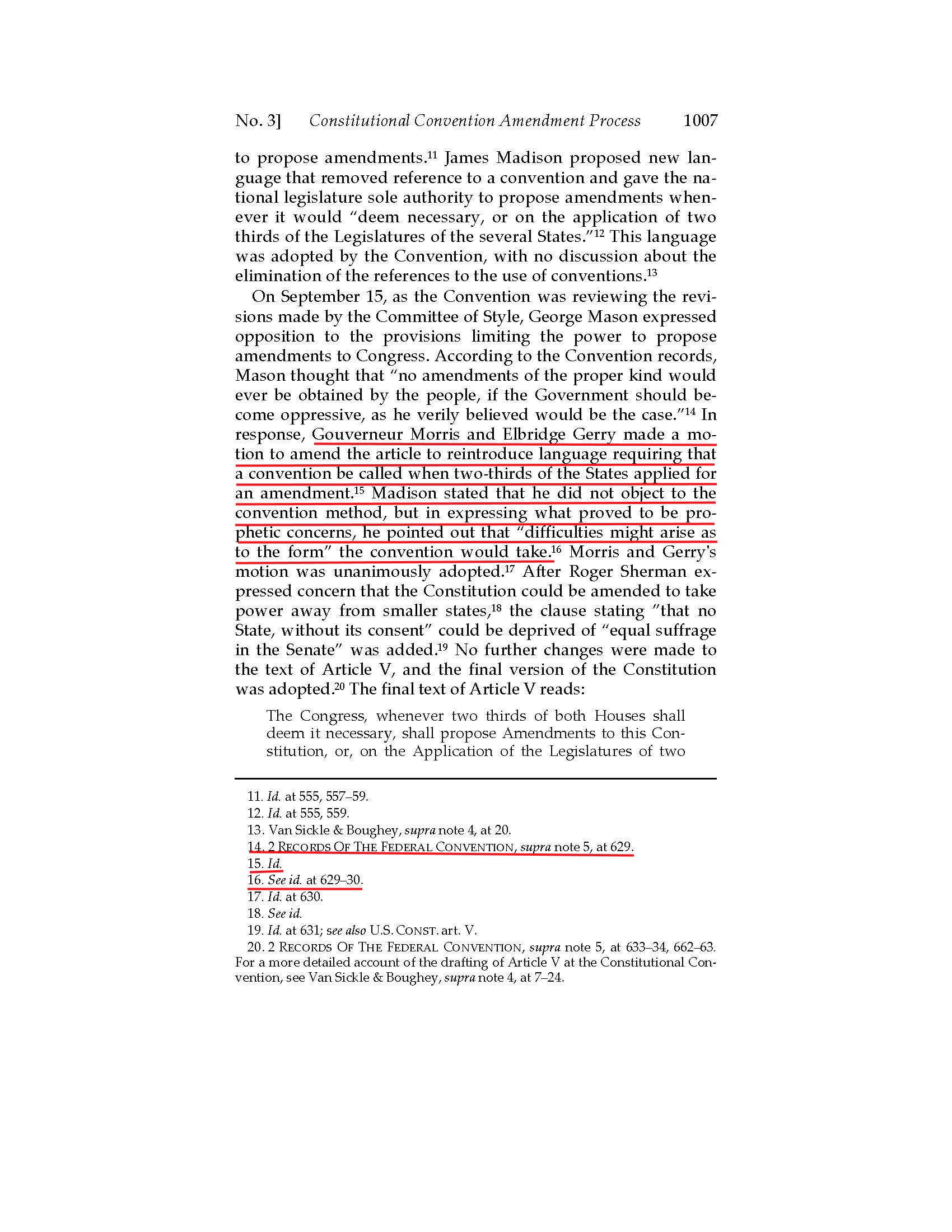

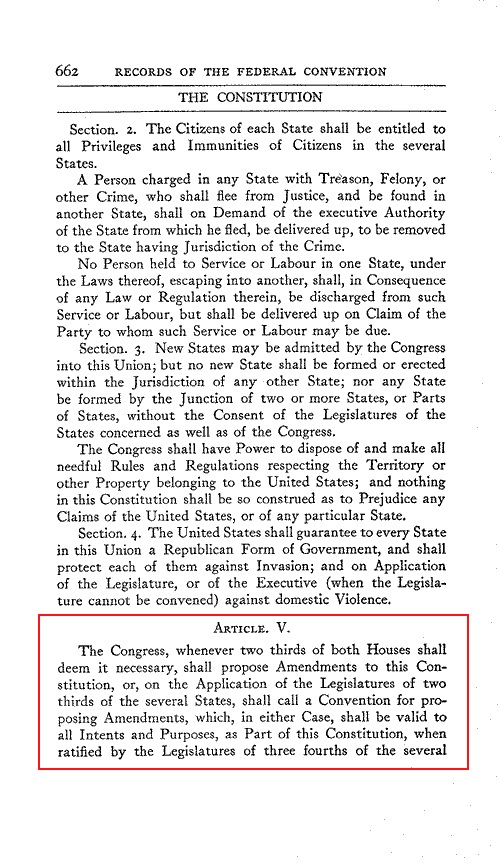

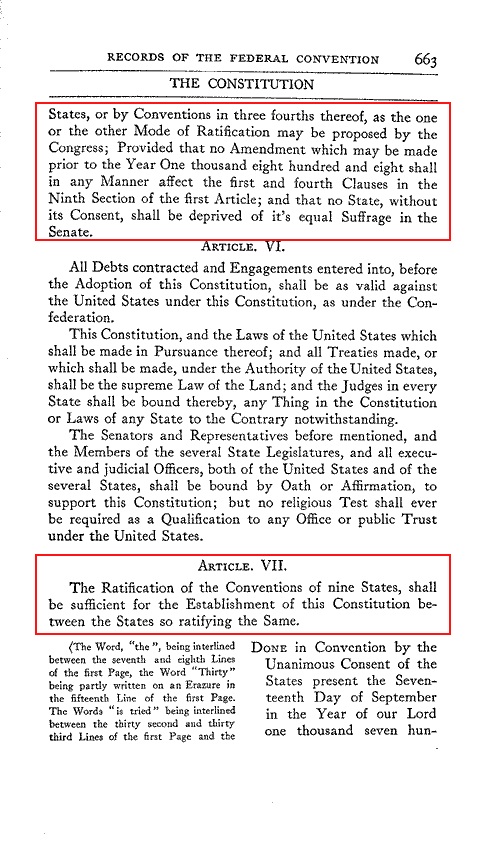

amendatory process. The committee had modified the text of Article XIX (see image far left, click to enlarge). Article XIX was

renamed Article V; the term "national legislature" was replaced with

the now familiar term, "Congress." The process of amendment proposal remained unchanged: proposal of amendments by Congress

or proposal of amendments on the application of the state

legislatures (if

Congress so agreed) followed

by ratification either by state legislatures or state "popular

ratification" conventions with Congress choosing the mode of

ratification. The "popular

ratification" convention intended to ratify the entire Constitution was firmly set in Article VII.

Having

received the report of the Committee of Style

and Arrangement on September 12, the Federal Convention of 1787 again

debated the various provisions of the revised text of the nearly

complete Constitution making numerous changes (See Page 12, Table 8). With

the convention only hours away from concluding its business on

Saturday, September 15 the convention "took up" the matter of the

amendatory process. The committee had modified the text of Article XIX (see image far left, click to enlarge). Article XIX was

renamed Article V; the term "national legislature" was replaced with

the now familiar term, "Congress." The process of amendment proposal remained unchanged: proposal of amendments by Congress

or proposal of amendments on the application of the state

legislatures (if

Congress so agreed) followed

by ratification either by state legislatures or state "popular

ratification" conventions with Congress choosing the mode of

ratification. The "popular

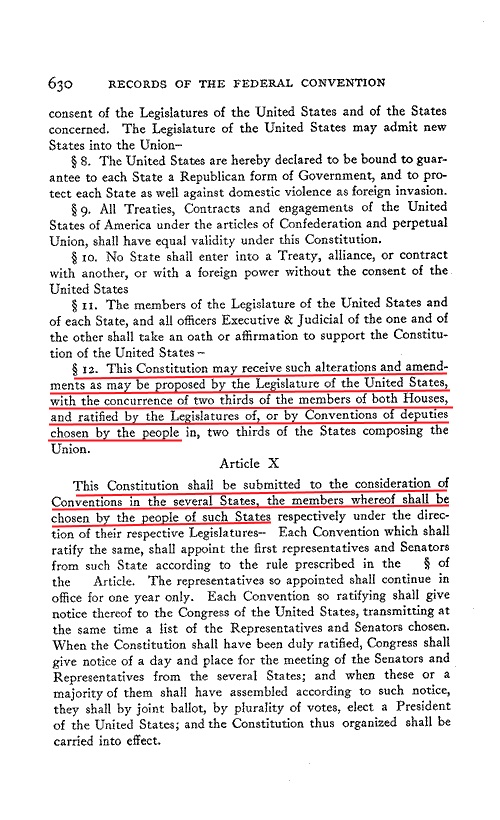

ratification" convention intended to ratify the entire Constitution was firmly set in Article VII. Farrand

describes several handwritten technical changes made by Madison (image right) to the text of Article V on the

committee report. These changes were: (1) crossing out "of two

thirds" and

inserting it again after "legislatures" so the phrase read, "...on the

application of the legislatures of two thirds of the several

States..."; removing the term " three-fourths at least of" and

inserting the term "of three-fourths" after the word "legislatures" so

the phrase read, "......ratified by the legislatures of three-fourths

of the several states,..."; crossing out the word "and" and inserting

"1&4 clauses in the 9" and inserted "the first" so the phrase read,

"...shall in any manner affect the 1 & 4 clauses in the 9 section

of the first article."

Farrand

describes several handwritten technical changes made by Madison (image right) to the text of Article V on the

committee report. These changes were: (1) crossing out "of two

thirds" and

inserting it again after "legislatures" so the phrase read, "...on the

application of the legislatures of two thirds of the several

States..."; removing the term " three-fourths at least of" and

inserting the term "of three-fourths" after the word "legislatures" so

the phrase read, "......ratified by the legislatures of three-fourths

of the several states,..."; crossing out the word "and" and inserting

"1&4 clauses in the 9" and inserted "the first" so the phrase read,

"...shall in any manner affect the 1 & 4 clauses in the 9 section

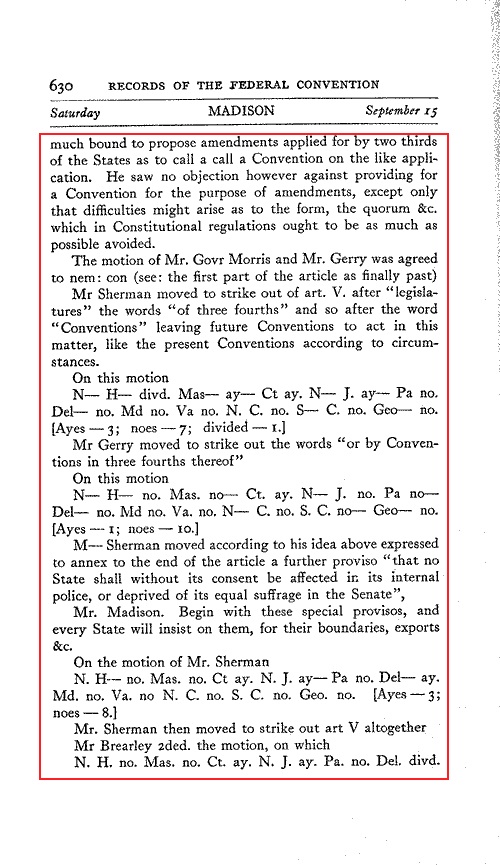

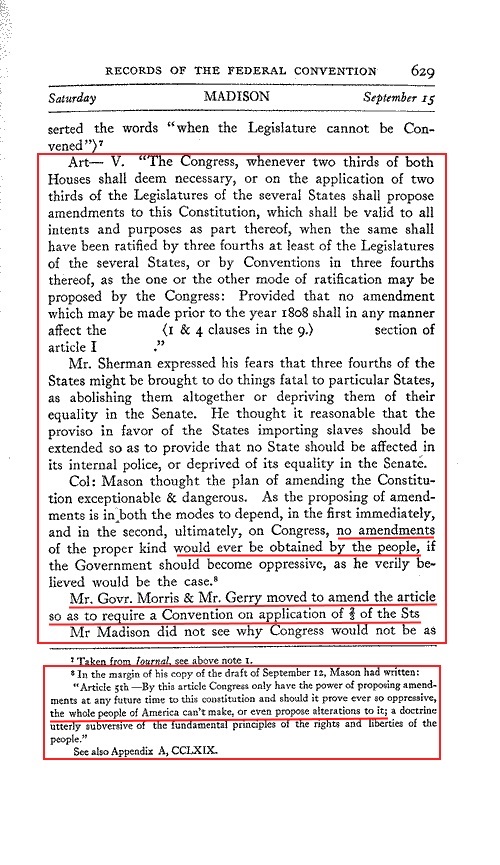

of the first article."However the text of Article V when taken up by the convention on September 15 differed from the handwritten modifications of Madison. As reported in his own notes Article V read, "Art--V. "The Congress, whenever two thirds of both Houses shall deem necessary, on the application of two thirds of the Legislatures of the several States, shall propose amendments to this Constitution, which shall be valid to all intents and purposes as part thereof, when the same shall have been ratified by three fourths at least of the Legislatures of the several States, or by Conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one or the other mode of ratification may be proposed by Congress: Provided that no amendment which may be made prior to the year 1808 shall in any manner affect the <1&4 clauses in the 9.> section of Article I." The term "two thirds" had not been moved. The phrase "three fourths at least" was still intact. The numeric "9" combined with the shorthand version of "1&4" and "article I" remained.

While there is no record of Madison's "corrections" being accepted by the convention presumably there was agreement to them as all appear in the final version (slightly modified to accommodate the requirements of English grammar and style). In the final version of Article V, the words "of two thirds" is moved to follow the word "Legislatures, the phrase "by three fourths at least" is altered to "...when ratified by the Legislatures of three fourths of..." and the numerals "1&4" are spelled out along with the proper written reference to the numeral "9" as is the term "article I." The final language reads, "...affect the first and fourth Clauses in the Ninth Section of the first Article;..." Finally the numeric designation of the year 1808 is written out as "Year One thousand eight hundred and eight." Presumably Madison raised these questions of grammar and style with the convention at some point (as they apparently had not been addressed by the committee) and obtained consent to modify the text which was granted without debate (as Madison phrased it, "nem: com"). As these were technical stylistic corrections Madison apparently saw no reason to record this fact in his notes.

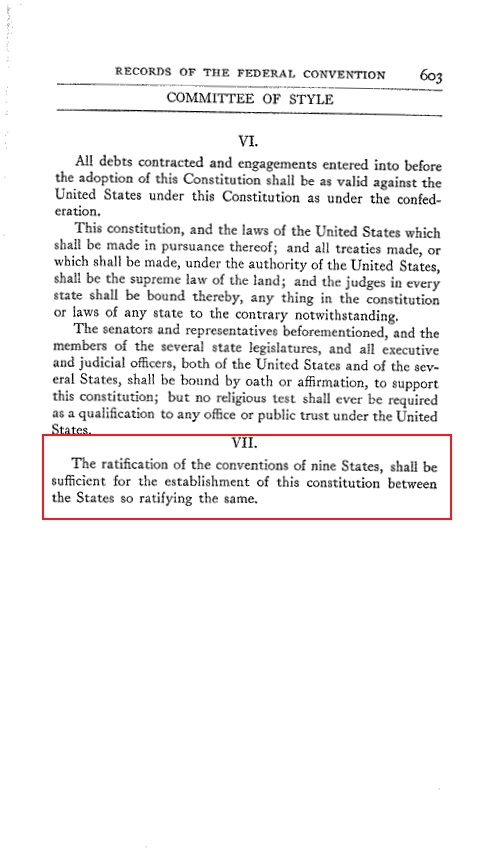

Article VII describing the ratification process for the entire Constitution had reached its final stage of language. Other than capitalizing several words in the sentence

(Ratification, Convention, Establishment and Same) the provision

remained untouched by the convention. The committee

text of September 15 read, "The ratification of the conventions of nine States, shall

be sufficient for the establishment of this constitution between the

States so ratifying the same" (image left). As noted in previous discussion, the intent of the 1787 convention, that of ratification by "popular ratification" conventions independent

of the state legislatures be executed in all states was so obviously

understood by all state legislatures this intent was executed without the need of further elaboration in the Constitution.

Article VII describing the ratification process for the entire Constitution had reached its final stage of language. Other than capitalizing several words in the sentence

(Ratification, Convention, Establishment and Same) the provision

remained untouched by the convention. The committee

text of September 15 read, "The ratification of the conventions of nine States, shall

be sufficient for the establishment of this constitution between the

States so ratifying the same" (image left). As noted in previous discussion, the intent of the 1787 convention, that of ratification by "popular ratification" conventions independent

of the state legislatures be executed in all states was so obviously

understood by all state legislatures this intent was executed without the need of further elaboration in the Constitution. Similarly, the word "conventions" in Article V contained no elaboration beyond describing the specific purpose of that "popular ratification" convention in the amendment process. This lack of elaboration shows while the delegates believed they needed to define the purpose of the convention with precise words, that is, describe what part the convention played in the amendment process, they did not believe it necessary to describe the meaning or intent of the word "convention." This was common knowledge understood by all in 1787. Therefore it was not necessary for the 1787 delegates to describe in the Constitution a convention was elected by the people and was independent of the state legislatures .

The record of the 1787 convention does not support the conclusion the meaning of the word "convention" in the proposal portion of the amendment process was to be any different than that as understood by the delegates in the same sentence for the ratification process. There is no evidence supporting a contention the 1787 convention intended a "popular ratification" convention to be limited only to ratification of an amendment proposal originated by the state legislatures. The word "convention" as used in its commonly understood meaning clearly allowed for a "convention" to give assent to an amendment which it proposed under the right of alter or abolish. The Supreme Court noted this fact in its discussion of common understanding of the words used in the Constitution in United States v Sprague (See: Page 17 K).

The Events of September 15

After

the convention "took up" Article V delegates addressed perceived issues

with the article as it stood. Roger Sherman "expressed his fears that

three fourths of the States might be brought to do things fatal to

particular States, as abolishing them altogether or depriving them of

the equality in the Senate. He thought it reasonable that the proviso

in favor of the States importing slaves should be extended so as to

provide that no State should be affected in its internal police, or

deprived of its equality in the Senate."

After

the convention "took up" Article V delegates addressed perceived issues

with the article as it stood. Roger Sherman "expressed his fears that

three fourths of the States might be brought to do things fatal to

particular States, as abolishing them altogether or depriving them of

the equality in the Senate. He thought it reasonable that the proviso

in favor of the States importing slaves should be extended so as to

provide that no State should be affected in its internal police, or

deprived of its equality in the Senate." George

Mason then spoke and said he "thought the plan of amending the

Constitution exceptionable & dangerous. As the proposing of

amendments is in both the modes to depend, in the first immediately,

and in the second, ultimately, on Congress, no amendments of the proper

kind would ever be obtained by the people, if the Government should

become oppressive, and he verily believed this would be the case."

Farrand cites a note written by Mason "in the margin of his

copy of the draft of September 12" which read, "Article 5th--By this

article Congress only have the power of proposing amendments at any

future time to the constitution and should it prove ever so oppressive,

the whole people of America can't make, or even propose alterations to

it; a doctrine utterly subversive of the fundamental principles of the

rights and liberties of the people." [Emphasis added].

George

Mason then spoke and said he "thought the plan of amending the

Constitution exceptionable & dangerous. As the proposing of

amendments is in both the modes to depend, in the first immediately,

and in the second, ultimately, on Congress, no amendments of the proper

kind would ever be obtained by the people, if the Government should

become oppressive, and he verily believed this would be the case."

Farrand cites a note written by Mason "in the margin of his

copy of the draft of September 12" which read, "Article 5th--By this

article Congress only have the power of proposing amendments at any

future time to the constitution and should it prove ever so oppressive,

the whole people of America can't make, or even propose alterations to

it; a doctrine utterly subversive of the fundamental principles of the

rights and liberties of the people." [Emphasis added].Mason's comments obviously were referring to the original committee of the whole resolution affirmed June 19 which as noted in the convention Journal stated, "It was moved and seconded to strike the following words out of the 19th resolution reported from the Committee of the whole House namely "to an Assembly or assemblies of representatives, recom-" mended by the several Legislatures, to be expressly chosen "by the people to consider and decide thereon" which passed in the negative [Ayes--3, noes--7.] On the question to agree to the 19th resolution as reported from the Committee of the whole House, namely Resolved that the amendments which shall be offered to the confederation by the Convention ought at a proper time or times after the approbation of Congress to be submitted to an assembly or assemblies of representatives, recommended by the several Legislatures, to be expressly chosen by the People to consider and decide thereon it passed in the affirmative [Ayes--9; noes--1]"

Under the terms of the proposed article as currently written at that time the "approbation of Congress" (a peremptory call) was addressed, as were the "recommended by the several Legislatures" (two thirds application by the several state legislatures) but the remainder of the resolution was not addressed--"an assembly or assemblies of representatives...to be expressly chosen by the People to consider and decide thereon..." As Mason noted, the language did not allow for a representative assembly expressly chosen by the people (not the state legislatures) to consider and decide thereon on amendment proposals. He therefore raised objection that the convention had ignored its own already passed resolution. Mason's objections lead to further revision of Article V.

The Convention "Trick"

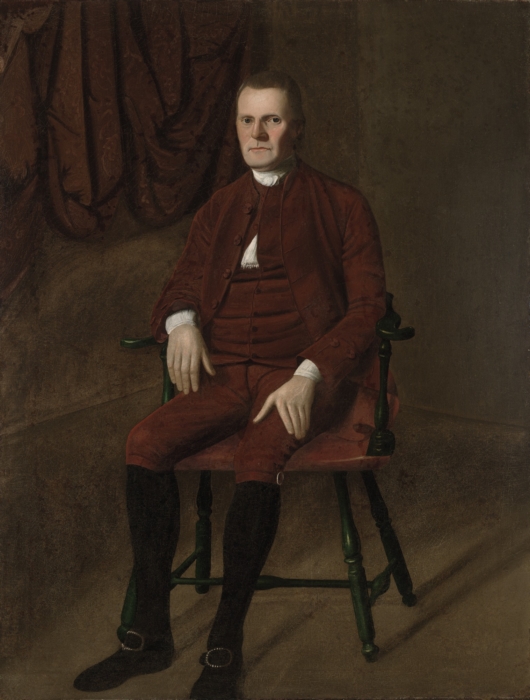

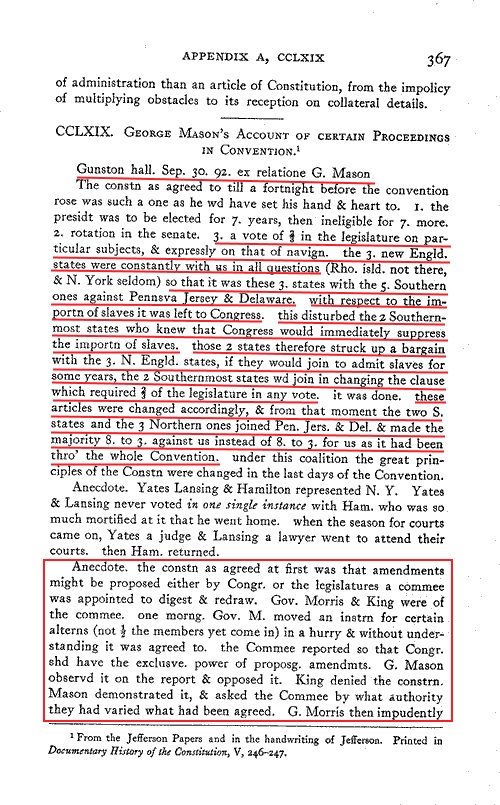

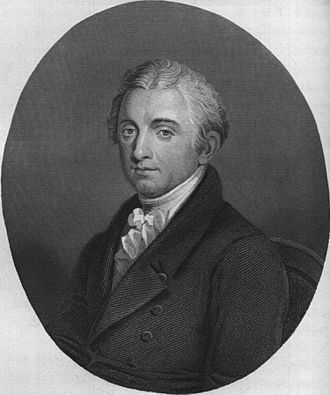

Farrand's notes regarding Mason's objections contain further citations

presented in Volume 3 of his work, pages 367-8 (images shown far left,

center, click to enlarge) and on page 379 (image near left, click to enlarge). Neither

version of the events discussed in Farrand, of the convention

"trick" were written by actual participants to the convention. Thomas Jefferson's [member

Continental Congress 1775-76; Governor of Virginia 1779-81; member

Confederation Congress 1783-84; Minister to France 1785-89; Secretary

of State 1790-93; Vice President 1797-1801; President of the United

States 1801-1809] (image right) rendition of Mason's

version of the event was recorded (according to Jefferson's notes) on

September

30, 1792 at Mason's estate, Gunston Hall, in Virginia. (However

historians

state Jefferson visited Gunston Hall on October 1, 1792). Mason died October 7, 1792.

Farrand's notes regarding Mason's objections contain further citations

presented in Volume 3 of his work, pages 367-8 (images shown far left,

center, click to enlarge) and on page 379 (image near left, click to enlarge). Neither

version of the events discussed in Farrand, of the convention

"trick" were written by actual participants to the convention. Thomas Jefferson's [member

Continental Congress 1775-76; Governor of Virginia 1779-81; member

Confederation Congress 1783-84; Minister to France 1785-89; Secretary

of State 1790-93; Vice President 1797-1801; President of the United

States 1801-1809] (image right) rendition of Mason's

version of the event was recorded (according to Jefferson's notes) on

September

30, 1792 at Mason's estate, Gunston Hall, in Virginia. (However

historians

state Jefferson visited Gunston Hall on October 1, 1792). Mason died October 7, 1792. Jefferson's version states Gouverneur Morris

(image left) "moved an instruction for certain alterations" regarding the amendment

process. Jefferson writes, "the constitution as agreed at first

was that amendments might be proposed either by Congress or the

legislatures. A committee was appointed to digest and redraw. ... The

committee reported so that Congress should have the exclusive power of

proposing amendments. ... Mason observed it on the report and opposed

it. Mason asked by what authority they had varied what had been agreed.

Morris then impudently got up and said by authority of the convention

and produced the blind instruction before mentioned." Jefferson then

notes, "They [the convention] then restored it as it stood originally."

Jefferson's version states Gouverneur Morris

(image left) "moved an instruction for certain alterations" regarding the amendment

process. Jefferson writes, "the constitution as agreed at first

was that amendments might be proposed either by Congress or the

legislatures. A committee was appointed to digest and redraw. ... The

committee reported so that Congress should have the exclusive power of

proposing amendments. ... Mason observed it on the report and opposed

it. Mason asked by what authority they had varied what had been agreed.

Morris then impudently got up and said by authority of the convention

and produced the blind instruction before mentioned." Jefferson then

notes, "They [the convention] then restored it as it stood originally."

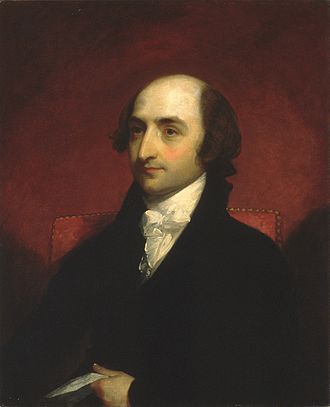

However

Farrand contradicts Mason's story a few pages later by

referring to comments made by Albert Gallatin [United States Senator

(PA) 1793-94; member of Congress (PA) 1795-1801; Secretary of Treasury

1801-14; Minister to France 1816-23; Minister to United Kingdom

1826-27] (image right) who told

a different version of the story on the floor of the House of

Representatives in 1798. Gallatin's version concerns words in the

Constitution "originally inserted... as a limitation

to the power of laying taxes." Gallatin states, "After the limitation

had been agreed to ... a member of the Convention, ... being one of a

committee of revisal and arrangement, attempted to throw these words

into a distinct paragraph, so as to create not a limitation, but a

distinct power. The trick, however, was discovered by a member

from Connecticut, now deceased, [Mason was from Virginia and according

to all reports never ventured out of Virginia in his entire lift except

to travel to the 1787 convention] and the words restored as they now

stand." Farrand states this phrase "words restored as they now stand"

related to the same incident described by Jefferson noting in a

footnote, "Quite probably the same as

related in CCLXIX [pages 367-8]." Thus in one version of the story the "trick"

related to the amendment process. In another version the same

"trick" related to the power of Congress to lay taxes. This is not the

only

example of persons of that time attempting to change the history of the

convention (See: Page 11 K).

However

Farrand contradicts Mason's story a few pages later by

referring to comments made by Albert Gallatin [United States Senator

(PA) 1793-94; member of Congress (PA) 1795-1801; Secretary of Treasury

1801-14; Minister to France 1816-23; Minister to United Kingdom

1826-27] (image right) who told

a different version of the story on the floor of the House of

Representatives in 1798. Gallatin's version concerns words in the

Constitution "originally inserted... as a limitation

to the power of laying taxes." Gallatin states, "After the limitation

had been agreed to ... a member of the Convention, ... being one of a

committee of revisal and arrangement, attempted to throw these words

into a distinct paragraph, so as to create not a limitation, but a

distinct power. The trick, however, was discovered by a member

from Connecticut, now deceased, [Mason was from Virginia and according

to all reports never ventured out of Virginia in his entire lift except

to travel to the 1787 convention] and the words restored as they now

stand." Farrand states this phrase "words restored as they now stand"

related to the same incident described by Jefferson noting in a

footnote, "Quite probably the same as

related in CCLXIX [pages 367-8]." Thus in one version of the story the "trick"

related to the amendment process. In another version the same

"trick" related to the power of Congress to lay taxes. This is not the

only

example of persons of that time attempting to change the history of the

convention (See: Page 11 K). There is no reference to these events in any report recorded at the time of the convention as related by Jefferson and Gallatin. The reference to Gouverneur Morris ("one of the members who represented the State of Pennsylvania") as the perpetrator of this "trick" wherein Mason alleges Morris "moved an instruction for certain alterations" to Article V is not supported by Madison's notes who obviously was present as part of the "half" Mason refers to in order to record Morris' comment. Neither Madison or the convention Journal record Morris making an actual motion (thus requiring a second and a recorded vote) in order to carry out the "trick" regarding his August 30 comment. Neither Jefferson or Gallatin had the benefit of reference to the actual records of the convention in order to verify the accuracy of their version of the story. That record would not be available until it was published by Farrand in 1911. Thus validity of the story depended on the recollection of a man who died less than a week later or an unnamed source who may or may not have actually witnessed the event.

The overall record of the convention does not support the proposition the convention "restored" the words as they stood before. As previously discussed (See: Committee of Detail Page Eleven G Detail III, VIII, IX, Final Report) had the delegates desired the state legislatures be able to amend the Constitution directly, they were quite capable of writing language expressing this unequivocally. Instead the convention removed the authority of direct state legislative amendment and replaced it with indirect application to Congress. Mason's own record of vote recorded at the convention contradict his version of the "trick." Mason correctly observes Congress was given the "exclusive" right of amendment proposal but this was because the substitution language offered by Madison on September 10 was adopted by the convention in place of language which allowed for direct amendment proposal by the state legislatures. Morris had nothing to do with Madison's proposal other than voting in favor of it. (The record shows the state of Pennsylvania voted in favor of Madison's proposal with no record of division such as was the case in that same vote in the state of New Hampshire. Thus all delegates from Pennsylvania favored the motion including Morris. This same record also shows Mason approved the substitution of language as there is no divided vote recorded for the state of Virginia).

While it is possible there was a "trick" played at the convention regarding language the exact details of that "trick" remain unclear. Possibly like other delegates (Madison, Mason) Morris wrote an informal note on his copy of the Committee of Detail report of August 6 and when called on by Mason produced that as the evidence referred to. Unlike Madison's changes to Article V which apparently were agreed to by the convention as they all appear in the final version, it's possible the convention made it clear informally they did not agree with Morris and thus "restored" the language only to later abandon that language entirely in favor of Madison's substitution language. Given the different versions of the story all related by persons not present at the convention and the fact records made at the time of the 1787 convention by those present do not bear out what was related in these versions constitutes strong evidence the convention never "restored" the right of legislatures to directly amend the Constitution once they voted to abandon that language in favor of Madison's substitution language. Further there is no indication this "restoration" if it occurred at all, altered in any way the common understanding of the meaning and intent of the word "convention" as discussed by the convention delegates and used by them in the Constitution. Attempting to use this allegory to prove direct control of a convention by state legislatures was the intent of the 1787 convention is unfounded.

The Article V Convention Clause

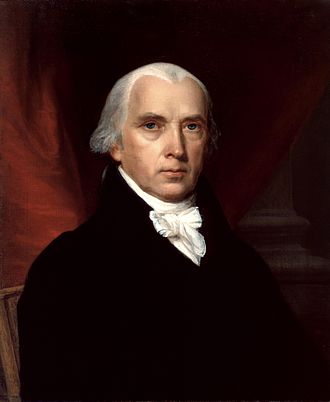

Following Mason's comments, Gouverneur Morris (image far left) and

Elbridge Gerry (center left) moved (and seconded) "to amend the article so as to

require a Convention on application of 2/3 of the Sts." Realizing

introduction of a convention in the proposal process introduced a second

mode of amendment proposal (by representatives expressly chosen by the

people) as opposed to proposal by Congress or the state

legislatures (the second mode removing the authority of state

legislatures to propose amendments) Madison, (nearest left) obviously

wishing to preserve the original

intent of his substitute language giving Congress control of all

aspects of amendment proposal, said he,"did not see why Congress would

not be as much bound to propose

amendments applied for by two thirds of the States as to call a call

a Convention on the like application." Madison then raised his

previous objections about the operational aspects of a convention saying,

"He saw no objection however against providing for a Convention for the

purpose of amendments, except only that difficulties might arise as to

the form, the quorum &c. which in Constitutional regulations ought

to be as much as possible avoided." (See images right, click to enlarge).

Following Mason's comments, Gouverneur Morris (image far left) and

Elbridge Gerry (center left) moved (and seconded) "to amend the article so as to

require a Convention on application of 2/3 of the Sts." Realizing

introduction of a convention in the proposal process introduced a second

mode of amendment proposal (by representatives expressly chosen by the

people) as opposed to proposal by Congress or the state

legislatures (the second mode removing the authority of state

legislatures to propose amendments) Madison, (nearest left) obviously

wishing to preserve the original

intent of his substitute language giving Congress control of all

aspects of amendment proposal, said he,"did not see why Congress would

not be as much bound to propose

amendments applied for by two thirds of the States as to call a call

a Convention on the like application." Madison then raised his

previous objections about the operational aspects of a convention saying,

"He saw no objection however against providing for a Convention for the

purpose of amendments, except only that difficulties might arise as to

the form, the quorum &c. which in Constitutional regulations ought

to be as much as possible avoided." (See images right, click to enlarge).Madison notes, "The motion of Mr. Govr Morris and Mr. Gerry was agreed to nem: con (see: the first part of the article as finally past)." Following this unanimous change in the amendment process for a "popular ratification" convention to propose amendments, Roger Sherman moved to "strike out of art. V. after "legislatures" the words "of three fourths" and so after the word "Conventions" leaving future Conventions to act in this matter, like the present Conventions according to circumstances." The convention voted seven against, three in favor, one divided. Mr. Gerry then moved to strike out the words "or by Conventions in three fourths thereof" which was defeated 10 states to one.

The 1787 convention by formal vote emphatically put any allegation an Article V Convention was intended to be a "constitutional convention" to rest. Sherman specifically moved the conventions described in Article V be able "to act...like the present Conventions according to circumstances." The only "present" convention (as the Constitution was not yet approved) Sherman could be referring to was the 1787 convention itself. By defeating his motion the convention slammed the door on any possibility an Article V Convention would be a "constitutional convention" but instead would be strictly limited to the purpose specified in the Constitution; to propose amendments to the present Constitution and, if the mode of ratification was so chosen by Congress, decide on the ratification of an amendment proposal or proposals.

Sherman

then moved, "according to his idea above expressed to annex to the end

of the article a further proviso "that no State shall without its

consent be affected in its internal police, or deprived of its equal

suffrage in the Senate" to which Madison responded, "Begin

with these special provisos, and every State will insist on them, for

their boundaries, exports &c." Sherman's motion was defeated eight

states to three. "Sherman then moved to strike out art V altogether"

which was defeated eight states against, two states in favor, one state

divided. "Mr. Govr Morris moved to annex a further proviso--"that no

State, without its consent shall be deprived of its equal suffrage in

the Senate." Madison states, "This motion being dictated by the

circulating murmurs of the small States was agreed to without debate,

no one opposing it, or on the question, saying no."

Sherman

then moved, "according to his idea above expressed to annex to the end

of the article a further proviso "that no State shall without its

consent be affected in its internal police, or deprived of its equal

suffrage in the Senate" to which Madison responded, "Begin

with these special provisos, and every State will insist on them, for

their boundaries, exports &c." Sherman's motion was defeated eight

states to three. "Sherman then moved to strike out art V altogether"

which was defeated eight states against, two states in favor, one state

divided. "Mr. Govr Morris moved to annex a further proviso--"that no

State, without its consent shall be deprived of its equal suffrage in

the Senate." Madison states, "This motion being dictated by the

circulating murmurs of the small States was agreed to without debate,

no one opposing it, or on the question, saying no."  George

Mason, "expressing his discontent at the power given to Congress by a

bare majority to pass navigation acts, which he said would not only

enhance the freight, a consequence he did not so much regard -- but

would enable a few rich merchants in Philada [Philadelphia] N. York [New York] & Boston, to

monopolize the Staples of the Southern States & reduce their value

perhaps 50 Per Ct--moved a further provision "that no law in nature of

a navigation act be passed before the year 1808, without the consent of

2/3 of each branch of the Legislature." The motion was defeated seven

states against, three in favor, one state divided. This vote completed work on Article V by the convention. The

alterations to Article V were the last recorded changes made to the

Constitution.

George

Mason, "expressing his discontent at the power given to Congress by a

bare majority to pass navigation acts, which he said would not only

enhance the freight, a consequence he did not so much regard -- but

would enable a few rich merchants in Philada [Philadelphia] N. York [New York] & Boston, to

monopolize the Staples of the Southern States & reduce their value

perhaps 50 Per Ct--moved a further provision "that no law in nature of

a navigation act be passed before the year 1808, without the consent of

2/3 of each branch of the Legislature." The motion was defeated seven

states against, three in favor, one state divided. This vote completed work on Article V by the convention. The

alterations to Article V were the last recorded changes made to the

Constitution. The convention then heard declarations by Randolph, Mason and Gerry saying they could not support the Constitution as written and were therefore withholding their signatures from it. All three men believed a second general convention was required in order to resolve the issues they saw with the Constitution. Randolph introduced a motion for a "second general Convention." The question of a second convention was unanimously defeated. The question "to agree to the Constitution as amended" was unanimously approved. The convention then ordered the completed Constitution to be engrossed "and "500 copies struck." The House adjourned at 6 p.m, Saturday, September 15, 1787.

On Monday, September 17, 1787 the Federal Convention of 1787 convened at 10 a.m. (its usual starting time) to read the engrossed copy of the Constitution and sign the now completed Constitution (Randolph, Mason and Gerry abstaining). The convention then removed the injunction of secrecy placed on the delegates at the beginning of the convention, instructed convention secretary William Jackson to "carry it [the Constitution] to Congress [meeting in New York], provided the members "with copies" of the Constitution and "adjourned sine die." "The gentlemen of the convention then dined together at the City Tavern." Thus, the path to a new Constitution which began on September 11, 1786 at Mann's Tavern in Annapolis, Maryland with the Annapolis Convention of 1786 ended on September 17, 1787 at the City Tavern in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania with the members of the Federal Convention of 1787 having dinner.

The

final version of Article V (see images left) as enrolled and transmitted to Congress on September 17, 1787 read as follows:

"The Congress, whenever two thirds of both Houses shall deem it

necessary, shall propose Amendments to this Constitution, or, on the

Application of the Legislatures of two thirds of the several States,

shall call a Convention for proposing Amendments, which, in either

Case, shall be valid to all Intents and Purposes, as Part of this

Constitution, when ratified by the Legislatures of three fourths of the

several States, or by Conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one

or the other Mode of Ratification may be proposed by the Congress;

Provided that no Amendment which may be made prior to the Year One

thousand eight hundred and eight shall in any Manner affect the first

and fourth Clauses in the Ninth Section of the first Article; and that

no State, without its Consent, shall be deprived of it's equal Suffrage

in the Senate." (See: Page 12, Table 10).

The

final version of Article V (see images left) as enrolled and transmitted to Congress on September 17, 1787 read as follows:

"The Congress, whenever two thirds of both Houses shall deem it

necessary, shall propose Amendments to this Constitution, or, on the

Application of the Legislatures of two thirds of the several States,

shall call a Convention for proposing Amendments, which, in either

Case, shall be valid to all Intents and Purposes, as Part of this

Constitution, when ratified by the Legislatures of three fourths of the

several States, or by Conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one

or the other Mode of Ratification may be proposed by the Congress;

Provided that no Amendment which may be made prior to the Year One

thousand eight hundred and eight shall in any Manner affect the first

and fourth Clauses in the Ninth Section of the first Article; and that

no State, without its Consent, shall be deprived of it's equal Suffrage

in the Senate." (See: Page 12, Table 10).

The Effect of the September 15 Changes to Article V

Beyond adding a clause prohibiting removal of a state from the United States Senate without its consent the primary effect of the change in language in Article V on September 15 was to alter the purpose of the applications submitted by the state legislatures to Congress. Prior to the Gerry/Morris amendment, that purpose as described in the September 10 version of Article XIX was to allow state legislatures to request Congress consider proposing an amendment(s) submitted by them in their applications. Based by Mason's comments (and the fact there no record of any delegate contradicting Mason's statement), Congress could refuse to propose the amendment requested by the states as there was no imperative in the language (i.e., "shall propose"). The original authority of amendment allowing state legislatures to directly propose amendment to the Constitution had long been discarded by the convention.

However the Gerry/Morris motion altered the purpose of the state legislature application from that of indirect amendment proposal to a new purpose. The final language of Article V changed the purpose of the application from requesting an amendment(s) to the Constitution proposed by Congress to requiring a convention call by Congress for the purpose of allowing direct election by the people of convention delegates who would then "consider and decide thereon" on the proposal of amendments thus circumventing Congress entirely. This process therefore satisfied Mason's objects regarding his fear that, "By this article Congress only have the power of proposing amendments at any future time to the constitution and should it prove ever so oppressive, the whole people of America can't make, or even propose alterations to it; a doctrine utterly subversive of the fundamental principles of the rights and liberties of the people." Described as "peremptory" by Hamilton the language of the motion dictated such "call" be "required" thus removing any discretion on the part of Congress to refuse the application for a convention (assuming two thirds of the state legislatures submitted applications). Thus Mason's concern that "no amendments of the proper kind would ever be obtained by the people" was addressed. [Emphasis added]. Mason made no mention of any concern regarding the fact amendments could not longer be obtained by the state legislatures. He apparently agreed with the sentiment expressed by Hamilton that "The State Legislatures will not apply for alterations but with a view to increase their own powers."

Thus Congress was mandated to call a "popular ratification" convention for the purpose of proposing amendments. There is no record of Mason raising objection to the Gerry/Morris motion saying that he intended state legislatures be able to propose amendments. The record shows Mason voted in favor of it as did all the convention. Given the understanding of the meaning of the word "convention" Mason obviously understood alteration of the language of Article V meant a convention rather than state legislatures would propose amendments. The alteration was unambiguous: before the Gerry/Morris motion, state legislatures could propose amendments in some capacity. After the Gerry/Morris motion, as note by Anti-Federalist 49, the "states, as states" could not propose amendment(s). Instead the other two elements of Article V, the people and Congress, were given authority of amendment proposal.

There is no doubt as to the meaning of the carefully chosen phraseology "a convention for proposing amendments." The fundamentals of English grammar leave nothing to speculation as to the heretofore unspecified purpose of the convention in regards to amendment proposal is unequivocally specified. There is no question under the rules of English grammar (and the record of the convention) a "popular ratification" convention was to propose amendments and not the state legislatures. The object of a phrase cannot be divorced from the affect of that phrase. The meaning and intent of the word "convention" therefore as used in three places in the Constitution, once later in the same sentence in Article V, requiring elected "popular ratification" conventions and again in Article VII calling for ratification of the entire Constitution by "popular ratification" conventions, all independent of Congress and state legislature, leave no doubt as to the intent and meaning of the word "convention" in the third instance.

As has been stated but bears repeating, for those inclined to ignore the public record in favor of their own unsupported hypothesis, had the convention intended state legislatures possess the authority of amendment proposal they would have written that authority into the Constitution in unmistakable terms requiring no "interpretation" such as labeling the convention for proposing amendments a "convention of states" in order to advance a particular political agenda favoring unconstitutional amendment proposal by the state legislatures. Indeed the record of the convention is emphatic: such authority was written in the language of the proposed Constitution in one form or another for nearly the entire time of the convention. Had the Convention intended the state legislatures be able to propose amendments or have authority to control a proposal convention they would have simply left the appropriate language in the Constitution. Instead the public record is absolutely irrefutable: the convention removed such authority entirely by affirmative vote, first on June 19 with Resolution 19 and later with the Gerry/Morris amendment to Article V.

The nebulous language of "for that purpose" of early versions of Article V was unequivocally defined on September 15: "a convention for proposing amendments." The state legislatures still determined whether a convention would be called by the submission of applications of two thirds of the several state legislatures. Legislatures still retained one of the two modes of ratification, the other by popular ratification convention both requiring assent by three fourths of the states before a proposed amendment became part of the Constitution. The state legislature mode of ratification became the most used, ratifying 26 of the 27 amendments in the Constitution. But as observed in Anti-Federalist 49 with the advent of the Gerry/Morris motion, "the states, as states" no longer could propose amendments.

Some may argue Madison's concerns about the convention expressed just after the proposed Gerry/Morris motion prove Madison opposed an Article V Convention. Their assertion is misplaced. These opponents fail to note Madison, after expressing his concerns, states the Gerry/Morris motion was adopted "nem: con" which means "no dissents, unanimously." Madison therefore voted in favor of the motion. As discussed elsewhere (see: Tuberville letter and May 5, 1789) Madison vigorously supported the intent and meaning of Article V. Moreover if state legislatures were intended to control a convention as many today assert, Madison's comments following introduction of the Gerry/Morris motion regarding operational procedure make no sense. If the Gerry/Morris motion was intended to allow state legislatures to control of the convention there would be no operational issues since the state legislatures would obviously make all such relevant decisions.

Madison's concerns regarding the operational aspects of a convention can be attributed to the fact he realized Congress was to be a continual body, that is, in session yearly with its membership spanning several sessions of Congress. Thus operational concerns for the amendment process for Congress were easy to address as the operational structure of Congress would already be established. On the other hand, a convention, not being a continual body and called whenever the state legislatures applied and being required to be created by election of delegates who would only hold office for the term of the convention, meant the convention had no operational structure in place. Madison could not know his concerns regarding operation of a convention would be addressed by the 14th Amendment which was added to the Constitution on July 28, 1868. The addition of the equal protection clause to the Constitution meant the short answer to Madison's concerns is a convention is organized "just like Congress" (See Page 18).

In sum, the "Convention for proposing Amendments" in Article V is no more than the operational extension of the right specified in the Declaration of Independence, "that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or abolish it and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness." The convention for proposing amendments or Article V Convention gives the people the operational means whereby they can exercise their right of alter or abolish by election of delegates "expressly chosen by the People to consider and decide thereon..."