The Events of August 30

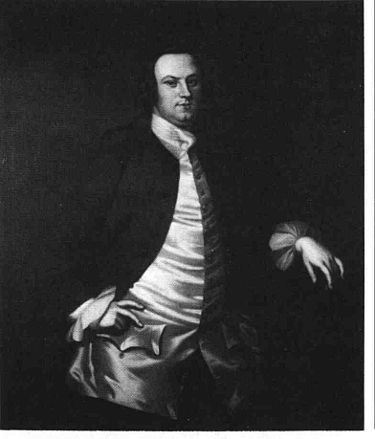

Following submission of the Committee of Detail final August 6 report was"taken up" and debated. The

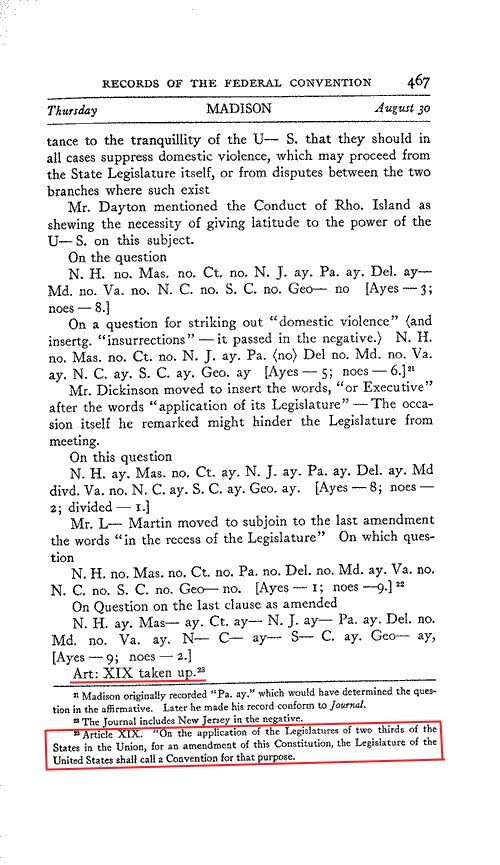

amendment proposal, numbered Article XIX, was "taken up" on

August 30 (images left). Article XIX read "On the

application of the Legislatures of two thirds of the States in the

Union, for an amendment of this Constitution, the Legislature of the

United States shall call a Convention for that purpose." Gouverneur

Morris [member Confederation Congress 1778-79,

United States Senator (NY) 1800-1803]. (image right) "suggested that the Legislature should be left

at liberty to call a Convention, whenever they please."

Following submission of the Committee of Detail final August 6 report was"taken up" and debated. The

amendment proposal, numbered Article XIX, was "taken up" on

August 30 (images left). Article XIX read "On the

application of the Legislatures of two thirds of the States in the

Union, for an amendment of this Constitution, the Legislature of the

United States shall call a Convention for that purpose." Gouverneur

Morris [member Confederation Congress 1778-79,

United States Senator (NY) 1800-1803]. (image right) "suggested that the Legislature should be left

at liberty to call a Convention, whenever they please." This comment is somewhat odd as the language of the proposal clearly allowed for only state legislatures to directly amend the Constitution. As the amendment was already proposed, the only purpose of the convention would be ratification. Letting the "Legislature of the United States" (Congress) call a convention "whenever they please" makes no sense unless Morris was suggesting the creation of a new amendment power: letting the Legislature of the United States (Congress) call a convention to propose amendments without needing state applications to do so. As matters stood on August 30, the text of Article XIX meant unless applications "for an amendment of the Constitution" were submitted by the state legislatures the National Legislature could not call the convention. Morris appears to suggest giving the National Legislature authority to amendment the Constitution. However Madison records no comments or response by any other delegate to Morris' comment. Following Morris' comment the text of Article XIX was agreed to without change.

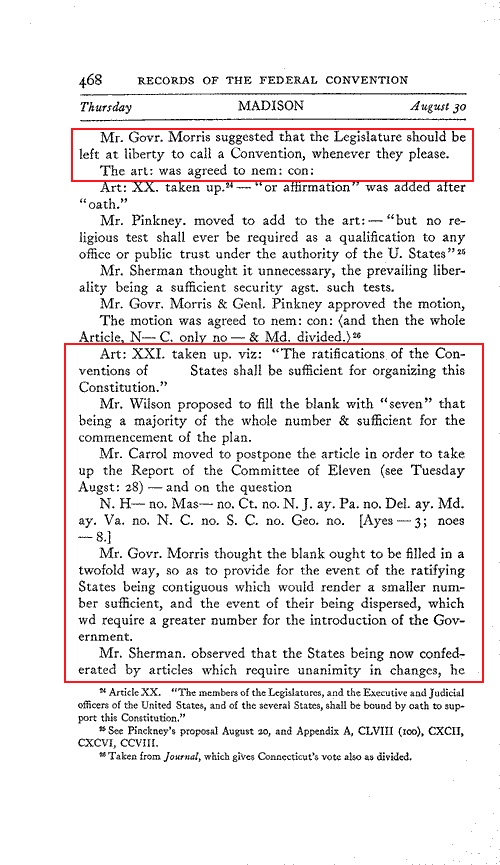

Also

"taken up" that day was the other convention in the Committee of Detail

report--the ratification convention for the Constitution as a whole,

Article XXI which stated, "The ratifications of the Convention of

[blank] States shall be sufficient for organizing this Constitution."

The delegates discussed several options on

the number to be inserted in the blank by the delegates. James Wilson

proposed "seven" "that being a majority of the whole number &

sufficient for the commencement of the plan."

Also

"taken up" that day was the other convention in the Committee of Detail

report--the ratification convention for the Constitution as a whole,

Article XXI which stated, "The ratifications of the Convention of

[blank] States shall be sufficient for organizing this Constitution."

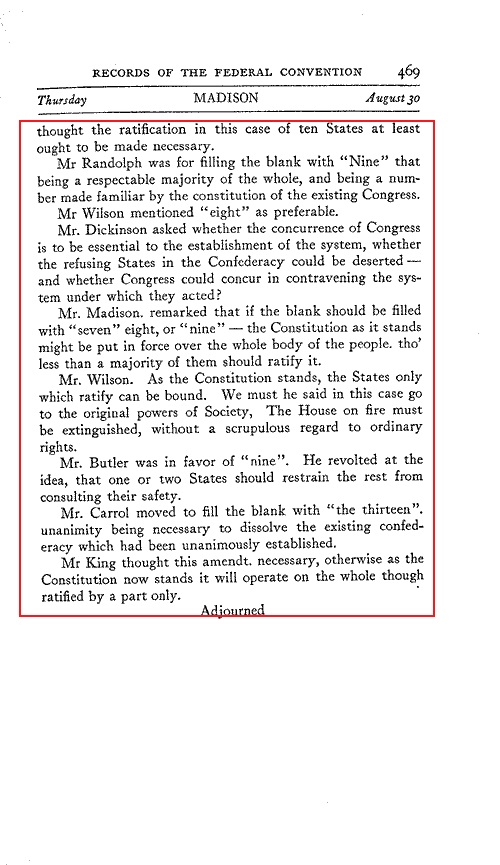

The delegates discussed several options on

the number to be inserted in the blank by the delegates. James Wilson

proposed "seven" "that being a majority of the whole number &

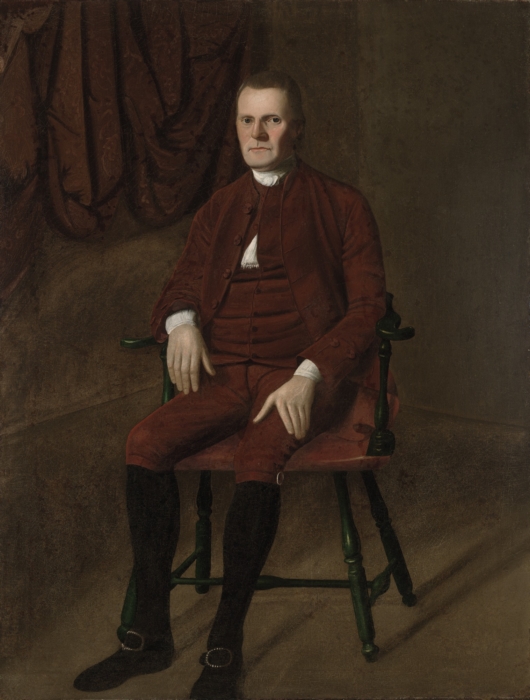

sufficient for the commencement of the plan." Gouverneur Morris suggested a "twofold way," a small number if the ratifying states were "contiguous" and a larger number if they were not. Roger Sherman suggested "ten" states. Edmund Randolph proposed "nine" states, "being a respectable majority of the whole." James Wilson then proposed "eight as preferable." James Madison noted "if the blank should be filled with "seven" eight, or "nine"--the Constitution as it stands might be put in force over the whole body of the people. tho' less than a majority of them should ratify it. Wilson then noted, "As the Constitution stands, the States only which ratify can be bound." Pierce Butler [member Confederation Congress 1787; United States Senator (SC) 1789-96, 1802-04)] (image far left) favored "nine" and "revolted at the idea that one or two States should restrain the rest from consulting their safety." Daniel Carroll [member of Congress (MD) 1789-91] (image near left) "moved to fill the blank with "the thirteen" "unanimity being necessary to dissolve the existing confederacy which had been unanimously established. The convention adjourned for the day without resolving the issue.

Significantly, the convention did not discuss whether ratification of the proposed Constitution should occur by means of the "popular ratification" convention. This method of ratification for the Constitution was apparently accepted without debate. Instead the focus was entirely on how many the state ratifying conventions was required before ratification took place and in some places whether the Confederation Congress should have a part in the ratification. There was no suggestion the state legislatures should control the convention thus using it as a surrogate for their conclusion as to ratification. The convention adjourned after its discussion with no vote on the number of required ratifications by convention needed to ratify the Constitution.

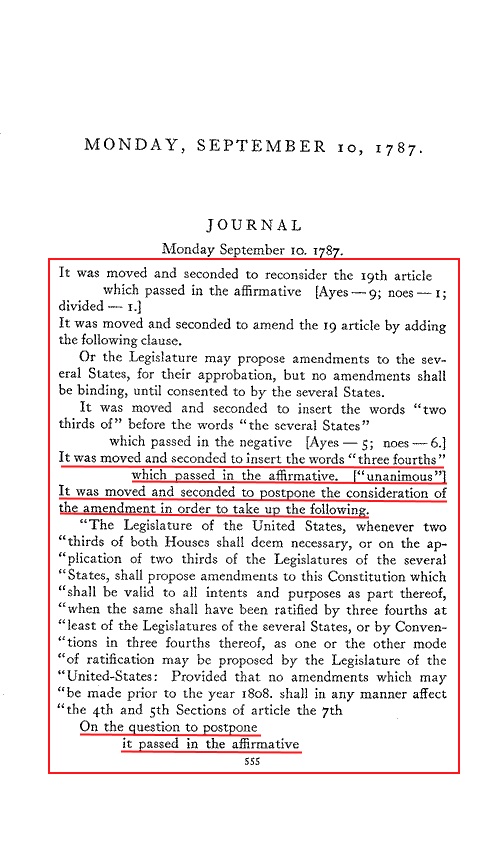

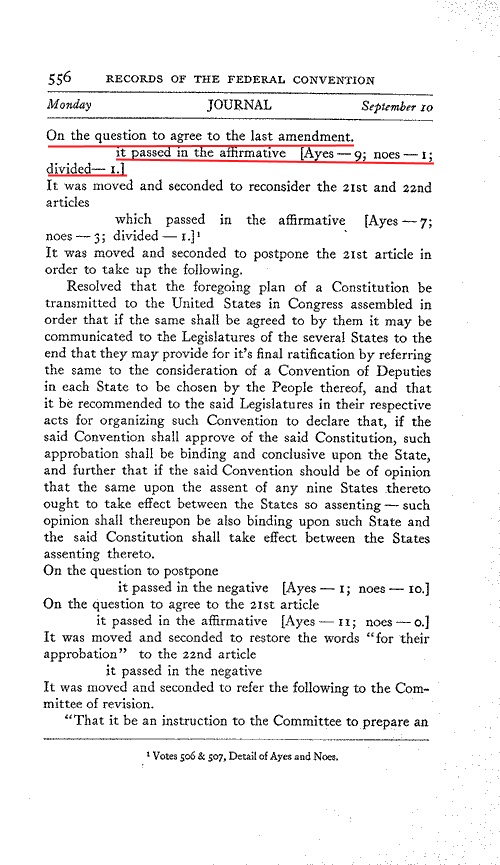

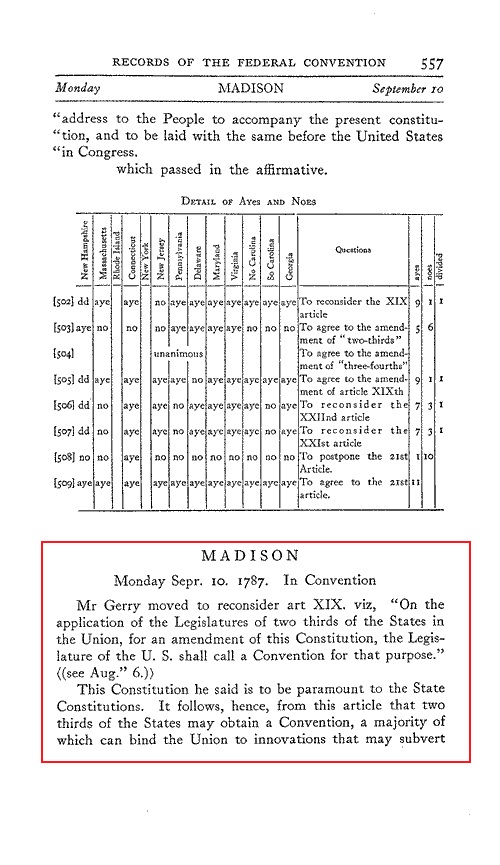

As described in the dry text of the convention Journal and more fully detailed in the notes of James Madison a momentous change occurred in Article V on September 10. Until then the convention had focused on altering the text of Article XIX of the Committee of Detail report. On September 10 the convention, after inserting a provision for ratification of proposed amendments as part of the amendment process and including a second mode of amendments proposal by the National Legislature into the August 6 text, then voted to "postpone" further work on that text (meaning scrap it as the convention never returned to August 6 text) in order to "take up" entirely new language for the text of Article XIX (soon to be labeled Article V by the just appointed Committee of Style and Arrangement (See Page Eleven J).

In his notes Madison states Elbridge Gerry (image right) moved to

reconsider Article

XIX, which, before modification read, "On the application

of the

legislatures of two thirds of the States in the Union, for an amendment

of this Constitution, the legislature of the U.S. shall call a

Convention for that purpose." Madison summarized Gerry's comments in

which the Massachusetts delegate expressed concern that as the Constitution was "to be

paramount to

the State Constitutions...it follows...from this article that two

thirds of the States may obtain a Convention, a majority of which can

bind the Union to innovations that may subvert the State-Constitutions

altogether. Gerry questioned whether this was a "situation proper to be

run into."

In his notes Madison states Elbridge Gerry (image right) moved to

reconsider Article

XIX, which, before modification read, "On the application

of the

legislatures of two thirds of the States in the Union, for an amendment

of this Constitution, the legislature of the U.S. shall call a

Convention for that purpose." Madison summarized Gerry's comments in

which the Massachusetts delegate expressed concern that as the Constitution was "to be

paramount to

the State Constitutions...it follows...from this article that two

thirds of the States may obtain a Convention, a majority of which can

bind the Union to innovations that may subvert the State-Constitutions

altogether. Gerry questioned whether this was a "situation proper to be

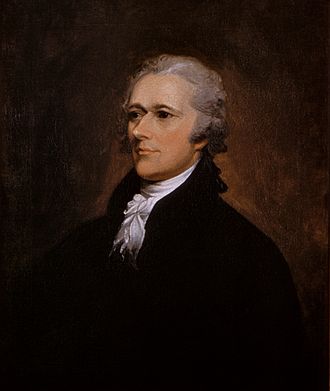

run into."  Alexander

Hamilton [member Confederation Congress, 1782-82, 1788-89; United States Secretary of Treasury, 1789-1795; Senior Officer of the Army, 1799-1800] (image right) seconded Gerry's motion but did so for different reasons that

Gerry. Hamilton agreed with Gerry's concerns but stated, "the mode now

proposed was not adequate." Hamilton stated the "State Legislatures

will not apply for alterations [of the Constitution] but with a view to

increase their own powers." Hamilton said he believed the "National

Legislature will be the first to perceive and will be most sensible to

the necessity of amendments, and ought also to be empowered, whenever

two thirds of each branch should concur to call a Convention." Hamilton

concluded, "There could be no danger in giving this power, as the people would finally decide in the case." [Emphasis added].

Alexander

Hamilton [member Confederation Congress, 1782-82, 1788-89; United States Secretary of Treasury, 1789-1795; Senior Officer of the Army, 1799-1800] (image right) seconded Gerry's motion but did so for different reasons that

Gerry. Hamilton agreed with Gerry's concerns but stated, "the mode now

proposed was not adequate." Hamilton stated the "State Legislatures

will not apply for alterations [of the Constitution] but with a view to

increase their own powers." Hamilton said he believed the "National

Legislature will be the first to perceive and will be most sensible to

the necessity of amendments, and ought also to be empowered, whenever

two thirds of each branch should concur to call a Convention." Hamilton

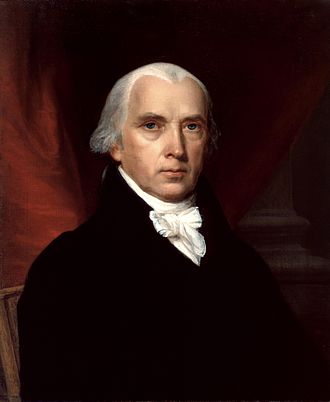

concluded, "There could be no danger in giving this power, as the people would finally decide in the case." [Emphasis added]. James Madison (image left)

then remarked on the vagueness of the term, "call a Convention for the

purpose" as sufficient reason for reconsidering the article. How was a

Convention to be formed? by what rule decide? what the force of its

acts?" Many anti-convention groups use this quote by

Madison in Farrand as proof Madison opposed an Article V Convention. As already discussed in two places on this site is the fact Madison always

favored all parts of Article V. Madison was obviously discussing

the amendatory process described in Article XIX created by the

Committee of Detail in its final report when he made his remark. He could not be referring the

final language of Article V as that text was yet to be written by the

convention. Moreover, while Madison expressed concerns about the

operational aspects of a

convention ("how...formed, ...rule decide,

...force of...acts") he did not express any concern about the overall

purpose of the convention (which was to allow for "popular

ratification" by the people of some portion of the amendment process)

nor state he opposed that

purpose. Madison therefore

clearly understand the use of a convention meant "popular

ratification" by the people either in the proposal or ratification process.

James Madison (image left)

then remarked on the vagueness of the term, "call a Convention for the

purpose" as sufficient reason for reconsidering the article. How was a

Convention to be formed? by what rule decide? what the force of its

acts?" Many anti-convention groups use this quote by

Madison in Farrand as proof Madison opposed an Article V Convention. As already discussed in two places on this site is the fact Madison always

favored all parts of Article V. Madison was obviously discussing

the amendatory process described in Article XIX created by the

Committee of Detail in its final report when he made his remark. He could not be referring the

final language of Article V as that text was yet to be written by the

convention. Moreover, while Madison expressed concerns about the

operational aspects of a

convention ("how...formed, ...rule decide,

...force of...acts") he did not express any concern about the overall

purpose of the convention (which was to allow for "popular

ratification" by the people of some portion of the amendment process)

nor state he opposed that

purpose. Madison therefore

clearly understand the use of a convention meant "popular

ratification" by the people either in the proposal or ratification process.The least favorable interpretation of Hamilton's comment of "the people would finally decide in the case [of amendment]" does not bode well for "same subject" "closed" convention advocates particularly given Hamilton's belief conventions should be elected by the people. If, as contended by Rogers the "purpose" of the convention was amendment proposal controlled by the state legislatures then it is clear Hamilton's remark does not refer to that kind of a "convention." There is no record of Hamilton (or anyone else at the convention) speaking in favor of state legislative control of a convention by determining its agenda or appointing it delegates (usually referred to as "commissioners" a term found nowhere in the Constitution). If the people "would finally decide in the case" this can only mean delegates to the convention elected by the people were entirely free to reject any the proposal by the legislatures and substitute their own under the sovereign right of alter or abolish or that as previously discussed the "purpose" of the convention was for ratification which also permitted the people to reject the amendment proposal of the state legislatures.

Gerry's

motion to reconsider passed nine states to one with one state

divided. Roger Sherman (image right) then moved to amend Article XIX by adding, "or the Legislature may propose

amendments to the several States for their approbation, but no

amendments shall be binding until consented to by the several States."

Thus, for the first time in the convention, Sherman formally introduced the process of ratification for

an amendment proposal. His motion created a second phase of the amendment process both of which had to be satisfied before an amendment proposal was adopted as part of the Constitution. Until Sherman's motion the amendment process was a single

phase process (direct proposal by the state legislatures) with the

convention called for some unspecified purpose (presumably ratification

but not expressly specified).

Gerry's

motion to reconsider passed nine states to one with one state

divided. Roger Sherman (image right) then moved to amend Article XIX by adding, "or the Legislature may propose

amendments to the several States for their approbation, but no

amendments shall be binding until consented to by the several States."

Thus, for the first time in the convention, Sherman formally introduced the process of ratification for

an amendment proposal. His motion created a second phase of the amendment process both of which had to be satisfied before an amendment proposal was adopted as part of the Constitution. Until Sherman's motion the amendment process was a single

phase process (direct proposal by the state legislatures) with the

convention called for some unspecified purpose (presumably ratification

but not expressly specified). Until Sherman's motion, the "popular ratification" convention for purpose of ratification had been vaguely inferred in the Committee of Detail version of the amendment process (as commented by Madison) by use of the term "for that purpose." The version failed to specify exactly what that "purpose" was. Sherman's motion filled in this gap but went even further. For the first time the power of the national "Legislature" (Congress) to propose amendments (not amendment) to the several states for "their approbation" was formally introduced. Thus the first phase of the amendment process (proposal) was now subdivided between the National Legislature (with the power to propose amendments) and the state legislatures who could propose an amendment directly.

While not specified in his motion, presumably Sherman's reference to "the several States" meant approbation by "popular ratification" conventions and was made in response to Madison's comment regarding the "vague" purpose of the convention in Article XIX. Hamilton's remark that there would be "no danger in giving [the national legislature] this power, as the people would finally decide in the case" [emphasis added] supports the case Sherman was referring to the use of a "popular ratification" convention to obtain "approbation" from "the several States." In their subsequent discussion of Article XXI (ratification of the Constitution by state "popular ratification" conventions) the delegates frequently used the term "states" to refer to ratification by convention rather than by state legislature.

Sherman himself used the term during that discussion. Madison's notes state, "Mr. Sherman was in favor of Mr. King's idea of submitting the plan generally to Congress. He thought nine States ought to be made sufficient: but that it would be best to make it a separate act and in some such form as that intimated by Col: Hamilton, than to make it a particular article of the Constitution."

Reasonably therefore, Sherman was referring to the use of a "popular ratification" convention when he used the term "states" particularly as, "popular ratification" by convention, if described in a version of the amendment process up to that point, was the only means for ratification thus far introduced in the convention. However, if Sherman was referring to ratification by state legislatures (and Madison's text fails to clarify whether Sherman made this point clear in discussion not recorded at the time) then his motion meant state legislatures could simultaneously propose and ratify "an amendment" to the Constitution.

James

Wilson (image right) then moved to insert "two thirds of" before the words "the several

States." The motion was defeated by a vote of 6-5. Wilson then moved

to insert "three fourths of" before "the several States" which was agreed

to unanimously. At this moment, the text of Article XIX read as

follows, "On the application of the

legislatures of two thirds of the States in the Union, for an amendment

of this Constitution, the Legislature of the United States shall call a

Convention for that purpose

or the Legislature may propose amendments to the

several States for their approbation, but no amendments shall be

binding until consented to by three fourths of the several States."

James

Wilson (image right) then moved to insert "two thirds of" before the words "the several

States." The motion was defeated by a vote of 6-5. Wilson then moved

to insert "three fourths of" before "the several States" which was agreed

to unanimously. At this moment, the text of Article XIX read as

follows, "On the application of the

legislatures of two thirds of the States in the Union, for an amendment

of this Constitution, the Legislature of the United States shall call a

Convention for that purpose

or the Legislature may propose amendments to the

several States for their approbation, but no amendments shall be

binding until consented to by three fourths of the several States."

Significantly, depending on how the term "the several States" was interpreted there was a clear imbalance of amendment power. As it stood after Wilson's proposal was approved, the national legislature had the power to propose "amendments." The state legislatures, while they could directly amend the Constitution, were limited to the proposal of a single "amendment." However, depending on how the term "the several States" was intended, state "popular ratification" conventions or state legislatures, the balance of amendment power could shift massively and irretrievably in favor of state legislatures if ratification by state legislature was the intent. State legislatures then possessed the power to both propose and ratify an "amendment" simultaneously as well preventing any proposed "amendments" from the National Legislature by simply not ratifying it.

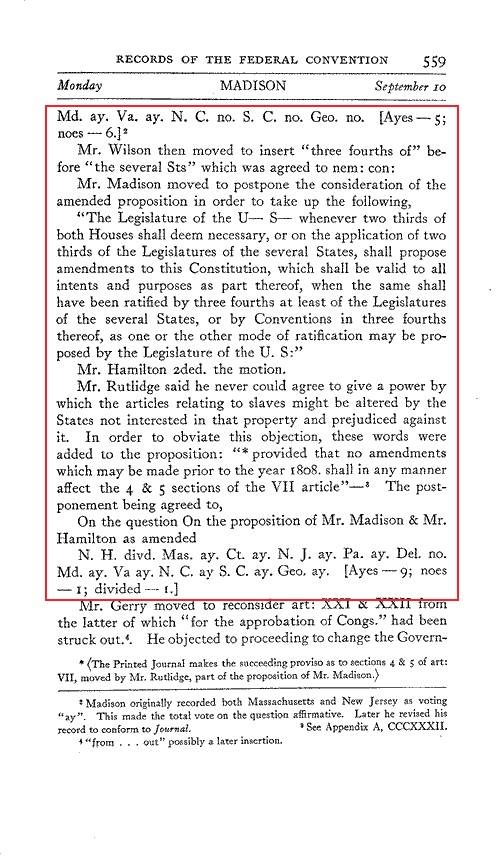

At this time Madison (image left) moved to "postpone the consideration of the

amended proposition in order to take up the following, "The Legislature

of the U-- S-- whenever two thirds of both Houses shall deem necessary,

or on the application of two thirds of the Legislatures of the several

States, shall propose amendments to this Constitution, which shall be

valid to all intents and purposes as part thereof, when the same shall

have been ratified by three fourths at least of the Legislatures of the

several States, or by Conventions in three fourths thereof, as one or

the other mode of ratification may be proposed by the Legislature of

the U.S:"

At this time Madison (image left) moved to "postpone the consideration of the

amended proposition in order to take up the following, "The Legislature

of the U-- S-- whenever two thirds of both Houses shall deem necessary,

or on the application of two thirds of the Legislatures of the several

States, shall propose amendments to this Constitution, which shall be

valid to all intents and purposes as part thereof, when the same shall

have been ratified by three fourths at least of the Legislatures of the

several States, or by Conventions in three fourths thereof, as one or

the other mode of ratification may be proposed by the Legislature of

the U.S:"

The

motion to postpone consideration of the amended proposition

(Article XIX) in favor of Madison's substitute language

was seconded by Alexander Hamilton (image right). However before the

convention voted to postpone and "take up" the substitute language, John

Rutledge (image left) objected saying, "he could never agree to give a power by which the

articles relating to slaves might be altered by the States not

interested in the property and prejudiced against it."

The

motion to postpone consideration of the amended proposition

(Article XIX) in favor of Madison's substitute language

was seconded by Alexander Hamilton (image right). However before the

convention voted to postpone and "take up" the substitute language, John

Rutledge (image left) objected saying, "he could never agree to give a power by which the

articles relating to slaves might be altered by the States not

interested in the property and prejudiced against it." Madison writes, "In order to obviate this objection, these words [moved by Rutledge] were added to the proposition: "provided that no amendments which may be made prior to the year 1808. shall in any manner affect the 4 & 5 sections of the VII article." Madison notes "the postponement being agreed to...the proposition of Mr. Madison & Mr. Hamilton as amended," was passed nine states in favor, one state opposed, one state divided. Thus the convention set aside the language of Article XIX (and all language preceding it) to begin discussion of Madison's new language.

At the end of the day the full text of Article XIX (as substituted and amended) read, "The Legislature of the U-- S-- whenever two thirds of both Houses shall deem necessary, or on the application of two thirds of the Legislatures of the several States, shall propose amendments to this Constitution, which shall be valid to all intents and purposes as part thereof, when the same shall have been ratified by three fourths at least of the Legislatures of the several States, or by Conventions in three fourths thereof, as one or the other mode of ratification may be proposed by the Legislature of the U.S; provided that no amendments which may be made prior to the year 1808. shall in any manner affect the 4 & 5 sections of the VII article." At this point the convention concluded it discussion of Article XIX and began discussion of Articles XXI and XXII dealing with ratification of the Constitution as a whole by "popular ratification" convention.

As recorded by Farrand the record of events of September 10 may be read below by clicking the images to enlarge.

|

|

|

|

|

The Effect of Madison's Substitution Motion on Article V

The effect of Madison's substitute motion replacing the language Article XIX created by the Committee of Detail in its report, five days before the convention concluded, meant the convention chose to throw out all previous versions of the amendment process for the Constitution and begin anew. Thus it rejected the recommendation of the Committee of Detail which essentially allowed for direct amendment of the Constitution only by the state legislatures. As the new text of Article XIX came late in the convention was only reviewed by the Committee of Style and Arrangement (on which Madison and Hamilton were members). The task of the committee was to polish the text of the Constitution rather than addressing the substance of any of its provisions. This meant any changes in text relating to substance of the amendment process originated on the convention floor following the submission of the committee's report on September 12 effectively transforming the convention into a Committee of the whole House for the purpose of drafting the final language of Article V.

By "postponing" discussion on the original text of Article XIX and substituting new language, the convention entirely abandoned that version of the amendment process meaning direct amendment of the Constitution by state legislature. The convention never again "took up" discussion of the original text of Article XIX. Any interpretation of the intent of the convention as to amendment of the Constitution based on the rejected versions of Article XIX made prior to Madison's substitution motion is therefore incorrect and irrelevant.

This said, however, the understanding of the elements making up the amendment process (state legislatures, "popular ratification" convention and national legislature) by the 1787 convention delegates remained unaltered. There is no language in the record of the convention indicating as a result of Madison's substitution motion, any convention delegate revised his understanding of the meaning of the word "convention;" a representative body elected by the people independent of both state and national legislative control, held for the purpose of reflecting the sovereign intent of the people as to a portion of the amendment process of the Constitution as described by the language of the amendatory article. The record of the 1787 convention makes it clear the convention rejected the definition advocated by the "close" "same subject" groups: a body unrepresentative of the people entirely controlled by the state legislatures and special interests.

Madison's motion transformed the state legislatures' ability of direct amendment to the Constitution into an indirect ability of application for amendments to the Constitution subject to approval of the national legislature. Had the convention intended to preserve the right of state legislatures to directly amend the Constitution, it would have simply retained the original language of Article XIX either by voting down Madison's motion or offering amendment to it such as was done by Sherman and Rutledge in order to restore that language to Article XIX. The effect was emphatic: while the state legislatures still retained the right of application, the purpose of the application was forever changed. No longer did the text of the amendment process expressly state the purpose of the application was "for an amendment of this Constitution." Instead the purpose of the application was altered so as to request another element of the application process (in this case the national legislature) textually assigned the task of amendment proposal consider whether to amend the Constitution as requested by the applications.

The effect of the word "amendments" in the motion and the continuing use of the singular form of the word "application" as well as the continued use of the grammatical phrase "on the application" from Article XIX on the application authority of the state legislatures cannot be disregarded. All "same subject" advocates believe the word "application" means "applications" from the state legislatures must be on the same amendment subject (or topic) before Congress is obligated to call a convention or in the case of Madison's September 10 motion, propose an amendment or amendments. This understanding is misplaced.

These advocates substitute the plural form of the word "application" (and its consequential grammatical intent) from that which is stated in the Constitution, which is the singular form of the word "application." Moreover they disregard the grammatical effect of the phrase in which the word "application" is placed. Under Madison's motion state legislatures no longer possessed authority to propose anything in the amendment process as the expressed purpose of the "application" had been altered from that of directly amending the Constitution to that of requesting another political body propose an amendment or amendments. Thus the singular "application" used in Madison's motion referred, not the unified subject matter of the "applications" by the various legislatures, but the process of the request as reflected in the phrase "on the application."

The word "application" was retained in its singular form so as reflect the fact each state was only required to submit a singleapplication in order to bring the matter of amendment to the attention of the national legislature. The use of the word "applications" within the phrase thus making it "on the applications" of the state legislatures would have indicated the legislatures were required to request multiple times (with no assurance of national legislature response) to bring the matter to the attention of the national legislature, a needless redundancy. The rules of English grammar allow for no other conclusion; the subject of a phrase cannot be separated from the intent of that phrase and the intent of the phrase must be surmised from all words within that phrase. The singular word, "application" as used in the phrase "on the application" thus referred to the action of application, that is, what should occur when the event described by the phrase takes place, rather than the subject matter within the application.

Further, as the states no longer could propose amendment or amendments, there was no longer any language (as existed in Article XIX) mandating the language of the application be identical either as to form or content. Thus it was no longer a requirement state legislatures agree on the subject matter of an application circulated amongst them but only on the need for an amendment(s)which they were able to arrive at independently for various reasons, rather than a singular reason. Thus state legislative applications no longer needed to contain the identical language or the same subject in order to "count" toward the two thirds requirement specified in Madison's motion. Madison's motion (and the subsequent discussion at the convention) make it clear the subject matter of the application had no bearing whatsoever on the amendment process.

The singular word "application" as used in the phrase "on the application" referred only to the aggregate conclusion by two thirds of the state legislatures requesting (at the time of Madison's motion) the national legislature consider proposing an amendment or amendments which might be on any the subject matters (or new subject matter if the national legislature so chose) of the various "applications" by the state legislatures. In short Madison's motion established the action of the application to cause consideration and the subject matter of the application were separate; the former causing the national legislature to consider proposing amendment(s), the latter considered by the national legislature when it did so.

Madison's motion assigned exclusive proposal power of amendments to the national legislature. The national legislature had, within its power, the ability to refuse the application by the state legislatures for a particular amendment or amendments regardless of the content or intent of state applications or the desire of the people to amend the Constitution. This fact would be the basis of further discussion of the amendment process by the convention on September 15. Thus the direct relationship established in the original text of Article XIX between state legislature application and direct amendment to the Constitution was severed. Madison's text firmly established whatever body (state legislature, national legislature or convention) which was textually assigned the power of amendment proposal operated independently of the state applications. Moreover given the already acknowledged authority of the people, it was clear the convention, like Congress, was entirely independent of the state legislatures and their applications and was therefore to propose amendments of their own design. Whether such action would be ratified by the state legislatures or the people acting through their ratification conventions, remained an open question but of course has been answered 27 times.

However instead the purpose of the state legislature application being for the calling a "popular ratification" convention to consider whether to amend the Constitution as had been the case in Article XIX, Madison ignored the convention mode entirely by creating an indirect convention, the national legislature, while elected in one house (the other chosen by state legislatures), was not directly elected by the people for the expressed purpose of proposal of amendments. Thus, at this point in the creation process of Article V, the people had no direct part whatsoever in the proposal of amendments and neither did the state legislatures. Madison's motion removed any possibility of the "popular ratification" convention proposing amendments as described in Article XIX (assuming the nebulous "purpose" was proposal rather than more logical ratification) leaving that authority entirely in the hands of the national legislature.

There is absolutely no question had Madison's original language remained unaltered amendment of the Constitution could only have occurred as a result of an application by the state legislatures to the national legislature for it to consider amending the Constitution or on national legislature's own initiative thus permitting the national legislature to entirely circumvent the American people by choosing the alternative mode of ratification, the state legislatures. Madison's motion however retained the "popular ratification" convention as a mode of ratification. It did not provide language asserting control of that convention by either the state legislatures or the National Legislature (other than authority by the national legislature to chose whether that mode of amendment ratification would be employed to ratify a particular amendment).

Finally, for all intents and purposes James Madison wrote the text of Article V. There is no record indicating that at any time following the convention did Madison repudiate his support for the text he himself wrote at the Federal Convention of 1787 including any alterations of that text following its submission by him to the convention on September 10. Indeed the public record of May 5, 1789 shows clearly Madison supported that text unequivocally. Any suggestion therefore that Madison "opposed" an Article V Convention is ludicrous.