With

its conclusion as the Committee of the whole on June 19 the

convention returned to its status as an original house. The first order

of

business was to accept the recommendations of the

Committee of the whole House. As it had in its committee form, the

convention addressed the

recommendations of the Committee of the whole House in order. It did

not discuss the amendment process described in Proposition 17 until

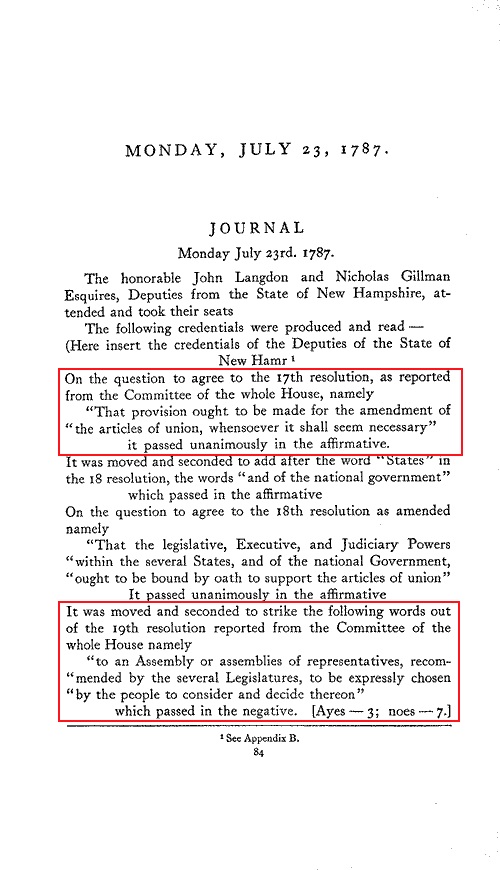

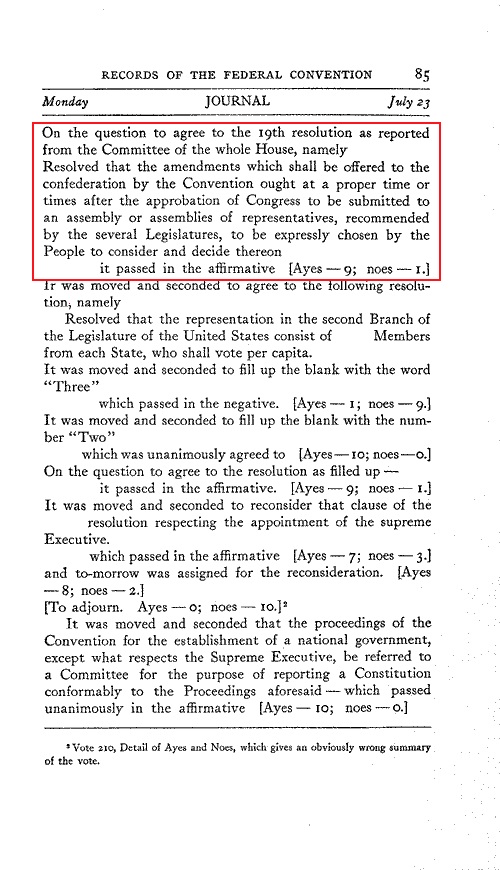

Monday, July 23 at which time, according to the

convention Journal, "On the question to agree to the 17th resolution,

as reported from the Committee of the whole House, namely "That

provision ought to be made for the amendment of the "the articles of

union, whensoever it shall seem necessary" it passed unanimously in the

affirmative." Similarly the 19th provision dealing with ratification of

the proposed Constitution was adopted after an effort was made to

strike the words affirming "popular ratification" from the proposal. Click

images left to enlarge.

With

its conclusion as the Committee of the whole on June 19 the

convention returned to its status as an original house. The first order

of

business was to accept the recommendations of the

Committee of the whole House. As it had in its committee form, the

convention addressed the

recommendations of the Committee of the whole House in order. It did

not discuss the amendment process described in Proposition 17 until

Monday, July 23 at which time, according to the

convention Journal, "On the question to agree to the 17th resolution,

as reported from the Committee of the whole House, namely "That

provision ought to be made for the amendment of the "the articles of

union, whensoever it shall seem necessary" it passed unanimously in the

affirmative." Similarly the 19th provision dealing with ratification of

the proposed Constitution was adopted after an effort was made to

strike the words affirming "popular ratification" from the proposal. Click

images left to enlarge.As noted in the convention Journal, "It was moved and seconded to strike the following words out of the 19th resolution reported from the Committee of the whole House namely "to an Assembly or assemblies of representatives, recom-" mended by the several Legislatures, to be expressly chosen "by the people to consider and decide thereon" which passed in the negative [Ayes--3, noes--7.] On the question to agree to the 19th resolution as reported from the Committee of the whole House, namely Resolved that the amendments which shall be offered to the confederation by the Convention ought at a proper time or times after the approbation of Congress to be submitted to an assembly or assemblies of representatives, recommended by the several Legislatures, to be expressly chosen by the People to consider and decide thereon it passed in the affirmative [Ayes--9; noes--1]"

During

the days following submission of the report of the Committee of the

whole House, convention delegates continued to amend the language of

the resolutions. While not expressly stated at any point in the

proceedings, it was clear by this time the recommendations of the

convention required to "render the federal constitution adequate to the

exigencies of Government & the preservation of the Union" were

far too extensive to simply be inserted as "alterations" in the current

text of the Articles of Confederation. Evidence of this is the fact the

convention made no

effort during its proceedings to examine the present language of

government contained in the Articles of Confederation and consider specific revisions to that already existing text.

During

the days following submission of the report of the Committee of the

whole House, convention delegates continued to amend the language of

the resolutions. While not expressly stated at any point in the

proceedings, it was clear by this time the recommendations of the

convention required to "render the federal constitution adequate to the

exigencies of Government & the preservation of the Union" were

far too extensive to simply be inserted as "alterations" in the current

text of the Articles of Confederation. Evidence of this is the fact the

convention made no

effort during its proceedings to examine the present language of

government contained in the Articles of Confederation and consider specific revisions to that already existing text.Instead the focus was entirely on creation of new text creating a new form of government which, of course, only a new document of government could explicate. The reason for this decision was the delegates generally considered the Articles of Confederation a failure. As succinctly described by James McHenry [member Maryland Senate 1781-86, 91-96; member Maryland state assembly 1789-91; member Continental Congress 1783-86; Secretary of War 1796-1800] (image right) on May 29 (quoting Randolph's speech explaining his Virginia Plan) "...the confederation fulfilled none of the objects for which it was framed." [Emphasis in original].

Realizing Randolph's proposals however extensively revised were still an outline of a governmental structure rather than an actual plan of government, the convention took the next step in the process of writing the Constitution on July 24. The convention created the Committee of Detail, which, as its name implies, was assigned to "fill in the details" regarding the recommendations of the Committee of the whole House. The committee was thus charged with writing the first draft of the Constitution.

|

|

|

|

|

The convention elected (shown in order above) John Rutledge [member Continental Congress 1776; Governor of South Carolina 1779-82; Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, 1789-91; Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, 1795], Oliver Ellsworth [member Continental Congress 1777-83; United States Senator (CT), 1789-96; Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, 1796-1800], Nathaniel Gorham, Edmund Randolph and James Wilson [member Continental Congress 1776; Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, 1789-98] to the Committee of Detail. Rutledge chaired the committee.

On July 26, the convention adjourned until August 6 in order to allow the Committee of Detail time to write the first draft of the Constitution (See Page 12, Table 6). During its work the committee wrote several drafts of language (See Page 12, Table 5). There is no record of committee minutes. Historians agree Rutledge in particular took great liberties by inserting provisions in the first draft of the proposed Constitution which were not based on any vote or resolution by the convention. Nevertheless many of theses provisions found their way into the final version of the Constitution. The first draft was heavily revamped from the date of its presentation on August 6 until September 10 when the revised draft was submitted to the Committee of Style and Arrangement for final drafting. As there was no record of the Committee of Detail report as it existed on September 10, Farrand reconstructed what the draft looked like (based on the record of changes made between August 6 and September 10) when it was submitted to the Committee of Style and Arrangement (See Page 12, Table 7).

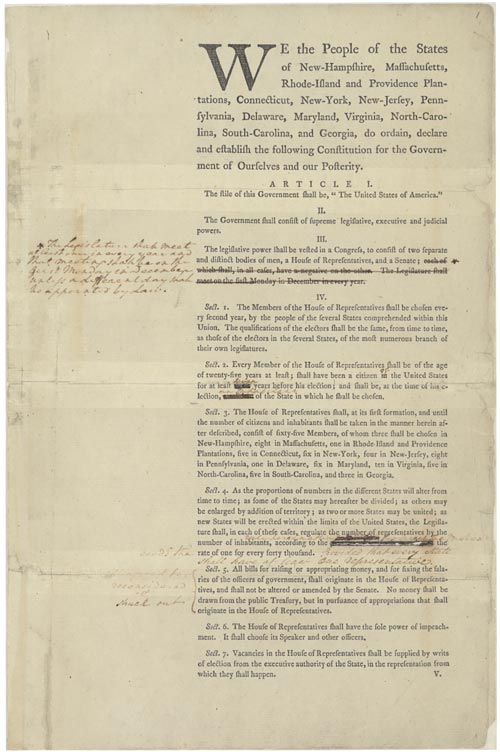

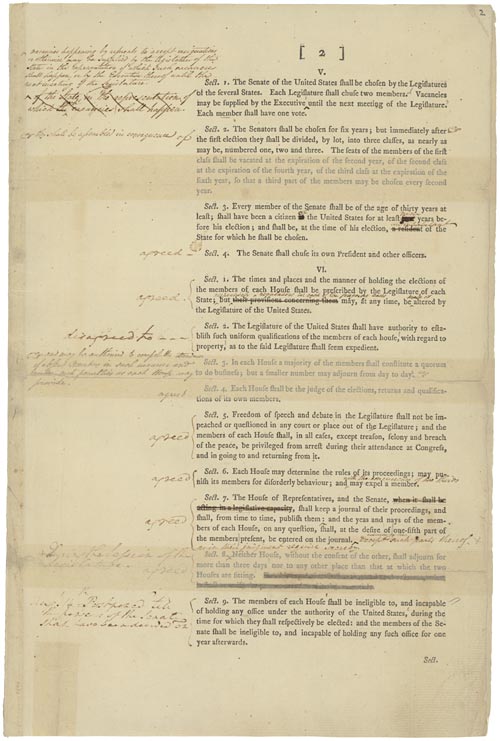

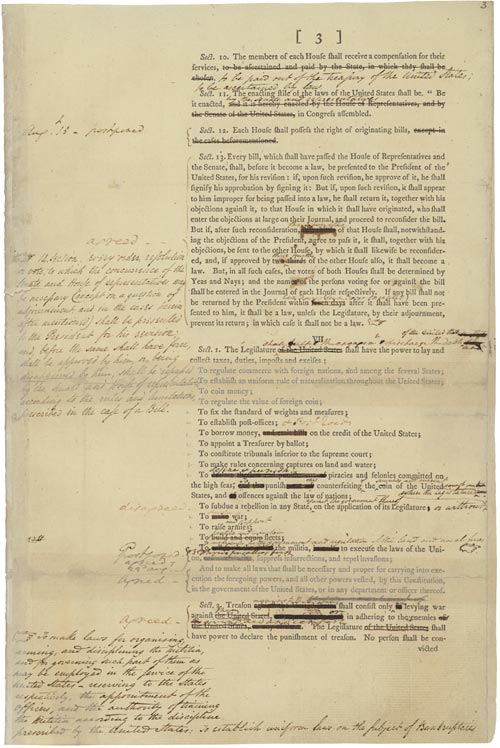

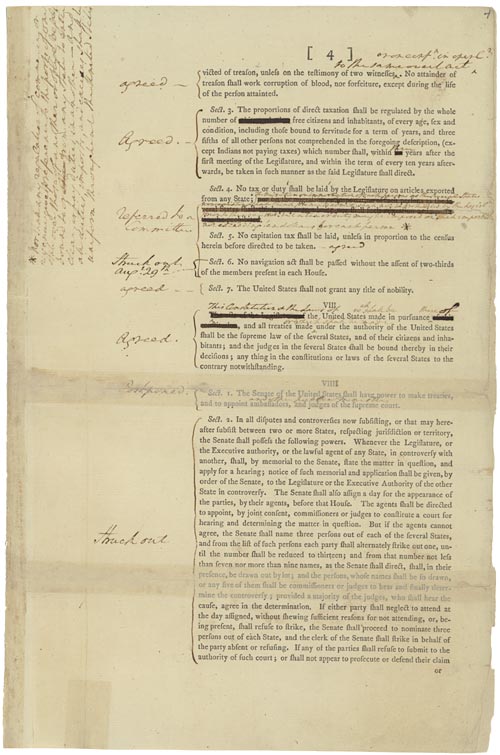

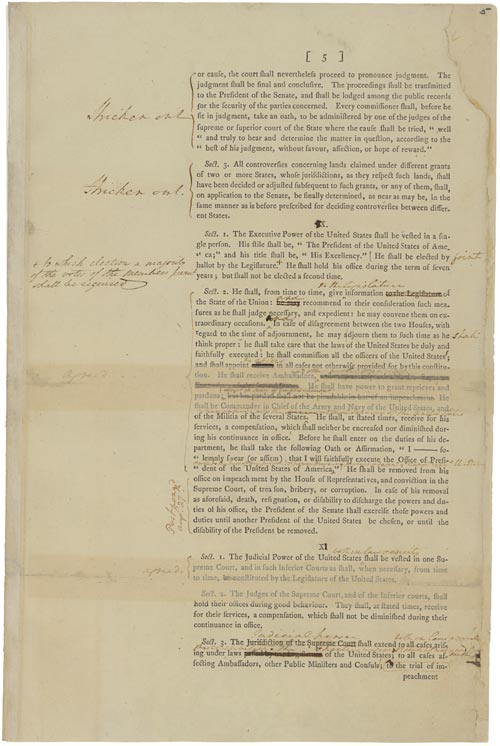

The

August 6 report by the Committee of Detail of the first draft of the

proposed Constitution was distributed to the convention on its release.

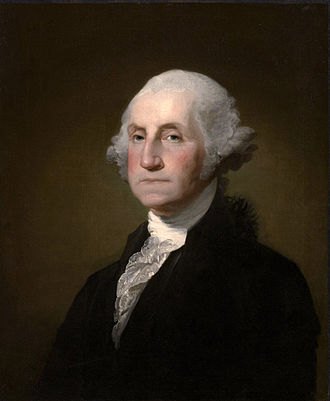

Many delegates including George Washington [First President of

the United States] used the report to write comments and other changes

to the proposed document. Washington's copy of the report together with

his notations can be read below. Click image to enlarge.

The

August 6 report by the Committee of Detail of the first draft of the

proposed Constitution was distributed to the convention on its release.

Many delegates including George Washington [First President of

the United States] used the report to write comments and other changes

to the proposed document. Washington's copy of the report together with

his notations can be read below. Click image to enlarge.  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

While there are no formal minutes of the Committee of Detail, several pages of notes apparently used by the committee in its two week process of drafting the proposed Constitution were discovered in the papers of James Wilson. Farrand replicated these pages in Volume 2 of his "Records of the Federal Convention of 1787" (See Page Twelve, Table 5). As noted by Farrand at the beginning of the section presenting the notes, "Among the Wilson Papers in the Library of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania are found a number of documents evidently relating to the work of the Committee of Detail. With a few additions from other sources, it is possible to present a nearly complete series of documents representing the various stages of the work of the Committee. All documents obtainable are here given." The documents were in sets which Farrand labeled with roman numerals. These numerals will be used as reference in the discussion below to examine the process of development of what was to become Article V of the Constitution. Apparently there are no dates associated with the documents. It is impossible therefore to determine when, during the two week session of the committee, the notes were transcribed except to assume they were written in the order presented. All images below may be clicked to enlarge.

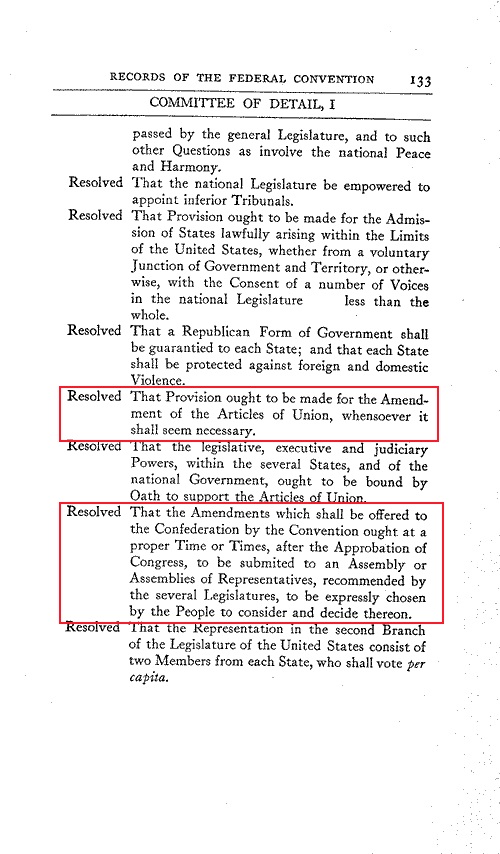

The

first document shown by Farrand regarding the amendment process is

Committee of Detail I, (See image left). Detail I is a

reprint of the Virginia Plan submitted to the Committee of

Detail by the Committee of the whole House. As discussed

the Committee of the whole House had already removed the provision, "and that assent of the National

Legislature ought not be required thereto" for further discussion. Also

immediately below Proposition 13 is Proposition 15 calling for "an

Assembly or Assemblies of Representatives... expressly chosen by the

People to consider and decide [Amendments which shall be offered to the

Confederation by the Convention] thereon."

The

first document shown by Farrand regarding the amendment process is

Committee of Detail I, (See image left). Detail I is a

reprint of the Virginia Plan submitted to the Committee of

Detail by the Committee of the whole House. As discussed

the Committee of the whole House had already removed the provision, "and that assent of the National

Legislature ought not be required thereto" for further discussion. Also

immediately below Proposition 13 is Proposition 15 calling for "an

Assembly or Assemblies of Representatives... expressly chosen by the

People to consider and decide [Amendments which shall be offered to the

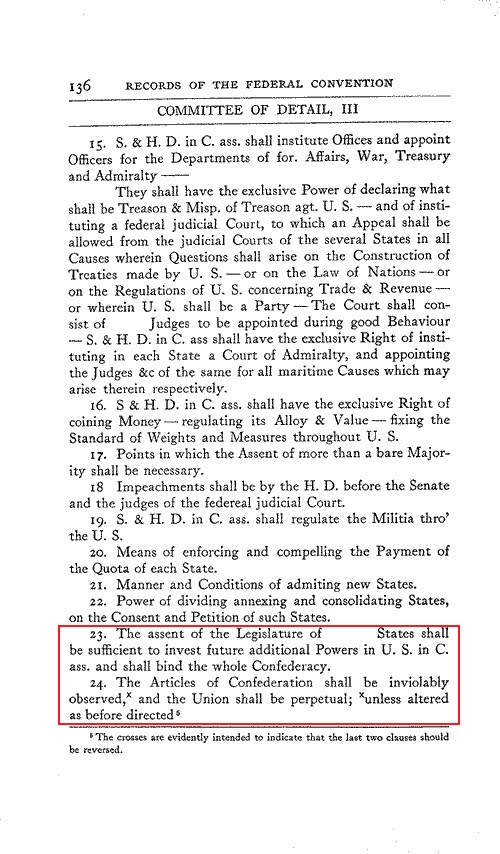

Confederation by the Convention] thereon."  The amendment process is again mentioned in Committee of Detail III, (see image right). The process reads, "The assent of the Legislature of [blank] States shall be

sufficient to invest future additional Powers in U.S. in C. ass. and

shall bind the whole Confederacy" and "The Articles of Confederation

shall be inviolably observed, unless altered as before directed, and

the Union shall be perpetual" According to Farrand, Committee of Detail III "is evidently an outline of the Pinckney Plan" (See Page Eleven K).

Farrand notes the New Jersey Plan was also referred to the Committee of

Detail. That particular plan however contains no reference to amendment or

convention and therefore is not presented. As noted by Farrand

there is some question as to exactly what provisions the Pinckney Plan

contained as there is no copy of the plan in existence dating from the

time of the 1787 convention.

The amendment process is again mentioned in Committee of Detail III, (see image right). The process reads, "The assent of the Legislature of [blank] States shall be

sufficient to invest future additional Powers in U.S. in C. ass. and

shall bind the whole Confederacy" and "The Articles of Confederation

shall be inviolably observed, unless altered as before directed, and

the Union shall be perpetual" According to Farrand, Committee of Detail III "is evidently an outline of the Pinckney Plan" (See Page Eleven K).

Farrand notes the New Jersey Plan was also referred to the Committee of

Detail. That particular plan however contains no reference to amendment or

convention and therefore is not presented. As noted by Farrand

there is some question as to exactly what provisions the Pinckney Plan

contained as there is no copy of the plan in existence dating from the

time of the 1787 convention. Whatever the source Committee of Detail III demonstrates beyond question if the Founders intended direct amendment authority by state legislatures they were quite capable of writing language expressing this process in unequivocal terms . The text makes it clear the "assent" of the state legislatures was all that was required in order to "alter" the Constitution (still referred to at this time as the Articles of Confederation). "Alteration" of the Constitution required no convention whatsoever thus excluding the people entirely from the amendment process providing them no means to exercise their sovereignty (See discussion Page Eleven F).

The sentences prove direct amendment by state legislature rendered a convention needless and redundant if direct amendment by state legislature were the object. The text of Committee of Detail III demonstrates such control is not required for the purposes of direct amendment by state legislature. Thus introducing a convention in the "alteration" process had to be deliberate act clearly not one regulated by the state legislatures as there was no need in direct amendment for this process. A convention in the amendment process therefore cannot be construed as intended to be controlled by the state legislature.

While the Committee of the whole House had voted to delay considering the question of amendment without the "consent of the National Legislature" the Committee of Detail ignored this and focused entirely on amendment without the "consent of the Nat'l Legislature" as the only mode of amendment for the Constitution. In none of its drafts does the Committee of Detail present a plan whereby the "Nat'l Legislature" was given any authority to propose amendments to the Constitution. That provision would be inserted later during the debates on the amendment process.

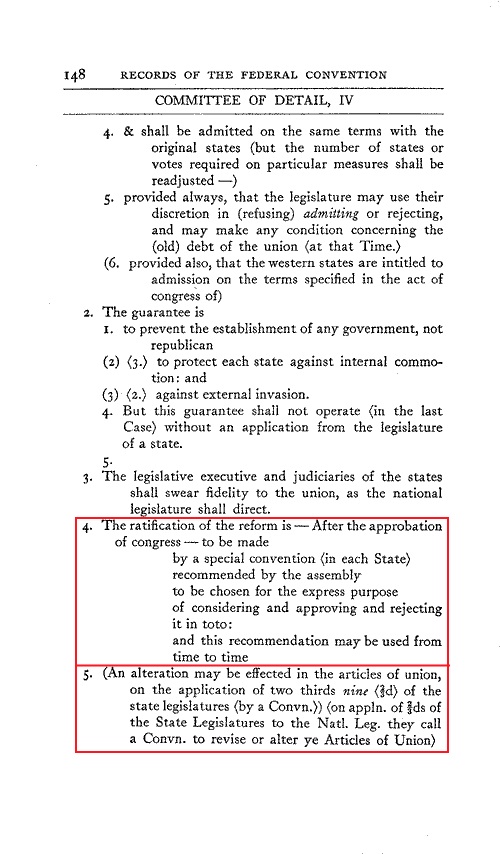

The amendment process is again addressed in

Committee of Detail IV, by which time the convention

process was described in both the ratification of the whole Constitution and the

subsequent amendment of the Constitution after ratification (see image left). As IV obviously came after III it follows the

language of Committee of Detail IV clearly revises the thinking expressed in Committee

of Detail III. Therefore it is

reasonable to assume the Committee of Detail had, by this time, rejected

the premise of direct amendment of the Constitution by the state legislatures expressed in

Committee of Detail III.

The amendment process is again addressed in

Committee of Detail IV, by which time the convention

process was described in both the ratification of the whole Constitution and the

subsequent amendment of the Constitution after ratification (see image left). As IV obviously came after III it follows the

language of Committee of Detail IV clearly revises the thinking expressed in Committee

of Detail III. Therefore it is

reasonable to assume the Committee of Detail had, by this time, rejected

the premise of direct amendment of the Constitution by the state legislatures expressed in

Committee of Detail III.In Committee of Detail IV the text of the ratification of the Constitution (numbered 4 in what appears to be an outline of points to be included in the text of the Constitution reads, "The ratification of the reform is--After the approbation of Congress--is to be made by a special convention <in each State> recommended by the assembly to be chosen for the express purpose of considering and approving and rejecting it in toto: and this recommendation may be used from time to time." [Emphasis added]. Immediately below is Number 5 in the outline describing the amendment process for the Constitution, "(An alteration may be effected in the articles of union, on the application of two thirds nine <2/3ds> of the state legislatures<by a Convn.>)(on appln. of 2/3ds of the State Legislatures to the Natl. Leg. they call a Convn. to revise or alter ye Articles of Union)."

The phrase "recommendation may be used from time to time" referring to a ratification convention intended to ratify the "reform" cannot mean repeated ratification of the Constitution as the new form of government. The Committee of Detail was fully aware of the difficulties of creating a new form of government. It was aware of the tenuous position of the present form of government (which satisfied "none of the objects for which it was framed"). To suggest it would place a term limit on the "reform" proposed by the 1787 convention is ludicrous. Therefore ratification of the "reform" was obviously intended to be a single event not requiring periodic affirmation.

The language of "recommendation may be used from time to time" therefore had refer to some other purpose for the convention described in Number 4 other than repeated ratification of the whole document. That purpose is obvious from the text of Number 5 which refers to a "convn." twice in two sentences. The text recognizes parts of the "reform" may require further revision or alteration and a convention is "used from time to time" to accomplish the task. The convention shall "revise or alter ye Articles of Union." An "alteration may be effected in the articles of union...by a conv." Thus in this draft of the amendment process the Committee of Detail first expresses what would become the convention process described in Article V, that a convention shall "revise or alter ye Articles of Union." The language does not express the state legislatures "shall revise or alter ye Articles of Union" but that a "Convn." shall "revise or alter ye Articles of Union." Thus the people by "popular ratification" shall "revise or alter ye Articles of Union" "from time to time" describing perfectly the convention amendment process ultimately placed in the Constitution.

Significantly, for the first time, a numeric ratio appears in the process. The numeric ratio clearly refers to the number of states needed to apply in order to cause Congress to call a convention which in turn would "revise or alter ye Articles of Union." Thus the Committee of Detail determined any need for "alteration" would be based on a numeric ratio of applying state legislatures but it would be the convention which would actually "revise" the Articles of Union.

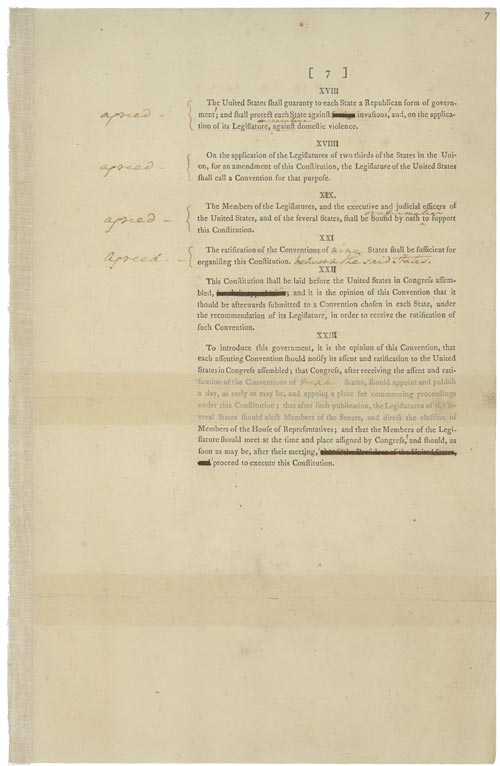

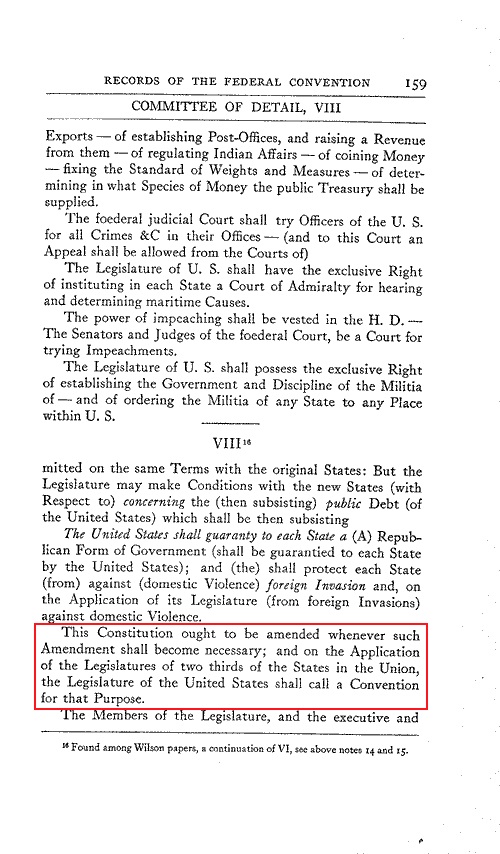

Committee

of Detail VIII again refers to the amendment process (see

image right). By this time

the language had been refined stating, "This Constitution ought to be

amended whenever such Amendment shall become necessary; and on the

Application of the Legislatures of two thirds of the States in the

Union, the Legislature of the United States shall call a Convention for

that Purpose."

Committee

of Detail VIII again refers to the amendment process (see

image right). By this time

the language had been refined stating, "This Constitution ought to be

amended whenever such Amendment shall become necessary; and on the

Application of the Legislatures of two thirds of the States in the

Union, the Legislature of the United States shall call a Convention for

that Purpose." The text introduces several elements. First, it refers to "Amendment" replacing the term "revise or alter." "Revise or alter" can refer to an entire document; "amend" is more limited. Second, Committee of Detail VIII uses the term "for that Purpose." Third, the text refers to "the Application" of the Legislatures of two thirds of the States in the Union." Finally, the term "Articles of Confederation" and "Articles of Union" have been replaced by the word "Constitution" thus reflecting the fact the Committee of Detail had, by this time, determined it was now writing a new document of government rather than "altering" the old document.

The singular use of the word "amendment," "application," and "purpose" make it clear, at this time in their thought process, the Committee of Detail intended the state legislatures have authority to offer a single "amendment" "whenever...necessary," by means of an "application" from two thirds of their number (the application obviously referring to the single "amendment" allowed by the proposed clause and thus becoming a "single subject" application) resulting in a convention called by the Legislature of the United States expressly "for that purpose."

The Committee of Detail VIII version of the amendment process appears, at first glance, to support the premise of Rogers. However two facts must be immediately remembered: this was not the final version of Article V nor even the final version of the thinking of the Committee of Detail. Second, as expressed on May 5, 1789, something was subsequently changed by the 1787 convention causing Congress to reject "same subject" as the basis for a convention call. Otherwise Bland's motion to refer the first state application to committee for "consideration" would have been accepted by the House and all subsequent applications from the state legislatures tabulated by Congress based on amendment subject which they are not.

Moreover, no mention is made in the text of Committee of Detail VIII expressing the convention called by Congress, while limited, was to be called for the purpose of proposing the amendment. Rather the use of the singular word "amendment" leads to the conclusion the language of the amendment was already proposed in the "application" received by Congress. No other possibility is plausible as the process of amendment called for in Committee of Detail VIII clearly requires mutual consent by two thirds of the state legislatures on a single amendment. To arrive at such consent requires (obviously) the application in question contain the exact language of the proposed single amendment being consented to by the state legislatures. However if the proposed amendment, upon consent of the requisite number of legislatures, becomes part of the Constitution, what purpose is served by the remainder of the provision?

The same logic of needless duplication expressed in Committee of Detail III applies here. Why call a convention "for that purpose" if the "purpose" is to propose an amendment the language of which has already been agreed to by those empowered to propose it? The only logical answer is the "popular ratification" convention was intended to ratify the proposed single amendment. The convention described in Committee of Detail VIII was not describing a proposing convention but rather a ratification convention autonomous of state legislative control. Such autonomy is obvious. There was no need for a "popular ratification" convention if that "popular ratification" were pre-determined by state legislatures by their already consented to "single subject" application. Therefore the convention had to have the authority of choice--whether to accept or reject the proposed amendment--as part of the Constitution with that decision binding on all. Significantly the Committee of Detail determined a convention could be expressly limited to a specific purpose, in this case, to considering ratification of a proposed amendment. This line of thinking was clearly the genesis of the state ratification conventions and the convention for proposing amendments provisions now in Article V.

However the Committee of Detail reworked its provisions, one thing is clear. The Committee of Detail understood they were describing an exact process of amendment analogous to using a recipe to bake a cake. Unless an ingredient is listed in the recipe it is not used to bake the cake. Unless a provision is expressly stated in the amendment process, it is cannot amend the Constitution. If absolute adherence to the exact amendment process described are varied (or ignored) in order to amend the Constitution, then the validity of the supremacy of the Constitution comes into question. As the Constitution is Supreme Law nothing can be supreme to it. If the Constitution is amended by a process other than described by the Constitution, that process must be supreme of the Constitution's process thus negating it. The Supreme Court determined in United States v Sprague this cannot be ruling only the expressed process described in the Constitution can amend the Constitution (See Page 17 K).

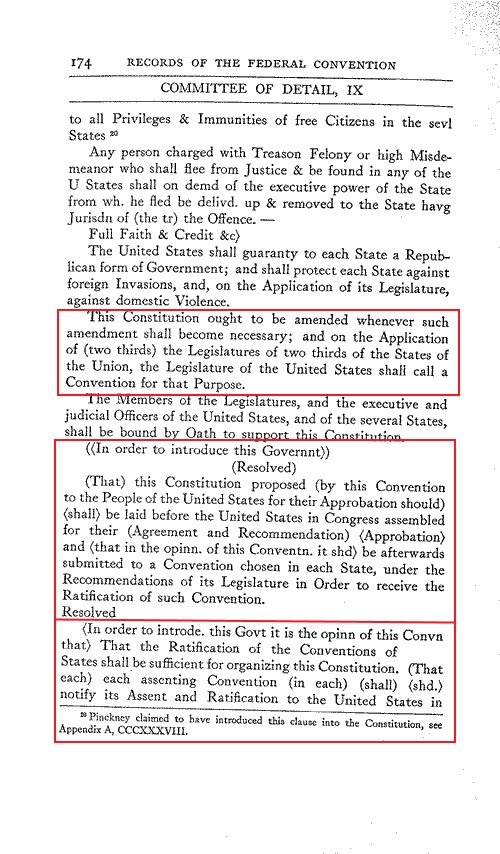

The final set of Committee of Detail notes in Farrand's collection is

Committee of Detail IX (see images left). The notes discuss two

conventions. The first is an amendment convention, the second a

ratification convention for ratifying the entire Constitution. The amendment

convention provision reads, "This Constitution ought to be amended

whenever such amendment shall become necessary; and on the Application

of (two thirds) the Legislatures of two thirds of the States of the

Union, the Legislature of the United States shall call a Convention for

that Purpose."

The final set of Committee of Detail notes in Farrand's collection is

Committee of Detail IX (see images left). The notes discuss two

conventions. The first is an amendment convention, the second a

ratification convention for ratifying the entire Constitution. The amendment

convention provision reads, "This Constitution ought to be amended

whenever such amendment shall become necessary; and on the Application

of (two thirds) the Legislatures of two thirds of the States of the

Union, the Legislature of the United States shall call a Convention for

that Purpose." The ratification convention provision states, "(That) this Constitution proposed (by this Convention to the People of the United States for their Approbation should)<shall> be laid before the United States in Congress assembled for their (Agreement and Recommendation) <Approbation> and <that in the opinn. of this Conventn. it shd> be afterwards submitted to a Convention Chosen in each State, under the Recommendations of its Legislature in Order to receive the Ratification of such Convention." The Committee of Detail obviously linked approbation (agreement) by "the People of the United States" to a convention. There is no text in the amendment convention provision indicating the Committee of Detail intended that convention to be anything other than the kind of convention described immediately below in its text describing the ratification convention, as an "approbation" by the people, not the state legislatures.

The text of Committee of Detail IX is exactly the same as Committee of Detail VIII. Thus state legislatures still proposed amendments directly while the convention served in its ratification capacity. To construe otherwise invites the needless redundancy already discussed in previous versions of the Committee of Detail notes.

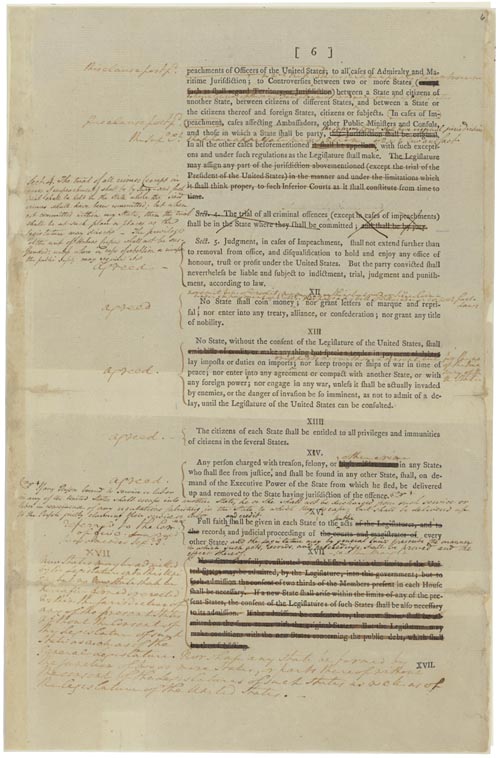

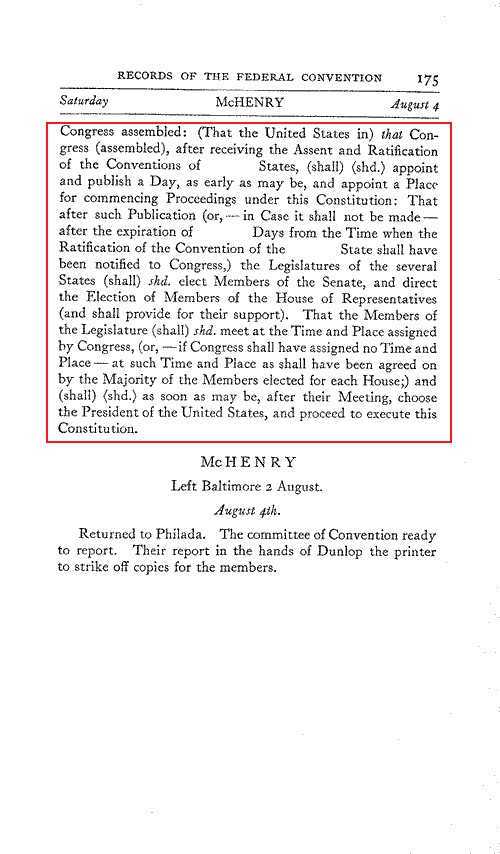

The final version of the Committee of Detail Report (See Page 12, Table 5) released to the convention on August 6, supports Rogers'

premise of direct amendment proposal by the state legislatures in clear

and unequivocal terms. Notably, the 2nd year law student failed to

mention this fact in his article. This proves however if

the Framers of

the Constitution intended

state legislatures have authority to propose amendment directly to the

Constitution, they were quite capable of stating this intent in

unmistakable language (see image right). Their revised text (labeled

Article XIX) reads, "On the application of the legislatures of two

thirds of the

States in the Union, for an amendment of this Constitution, the Legislature of the United States shall call a Convention for that purpose." [Emphasis added].

The final version of the Committee of Detail Report (See Page 12, Table 5) released to the convention on August 6, supports Rogers'

premise of direct amendment proposal by the state legislatures in clear

and unequivocal terms. Notably, the 2nd year law student failed to

mention this fact in his article. This proves however if

the Framers of

the Constitution intended

state legislatures have authority to propose amendment directly to the

Constitution, they were quite capable of stating this intent in

unmistakable language (see image right). Their revised text (labeled

Article XIX) reads, "On the application of the legislatures of two

thirds of the

States in the Union, for an amendment of this Constitution, the Legislature of the United States shall call a Convention for that purpose." [Emphasis added]. As with Committee of Detail III and VIII, however the language of the final report raises the question of redundancy once again. What "purpose" is served by calling a convention when the text of the article clearly states it is the state legislatures which propose the amendment? Again the answer can only be the Committee of Detail intended the "popular ratification" convention to be a ratification convention independent of the state legislatures and thus able to make final determination of whether the proposed amendment became part of the Constitution.

The phrase "for an amendment of this Constitution" defines both the purpose and authority of the application by the state legislatures. The purpose of the application, to create "an amendment of this Constitution," is clearly assigned to the state legislatures. Had this version of the amendment process proposed by the Committee of Detail remained unaltered Rogers would be correct in the premise of his article. Indeed there would be no need for his article as the process presumably would have already amended the Constitution numerous times. However, as various Supreme Court rulings describing the amendment process of Article V have never expressed state legislatures have the authority to directly propose amendment as described in the final report of the Committee of Detail, obviously this was not the final text nor final intent of Article V.

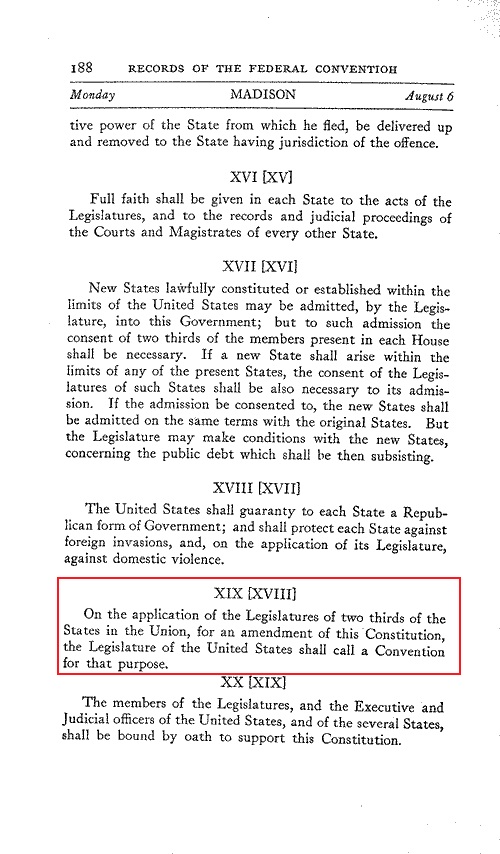

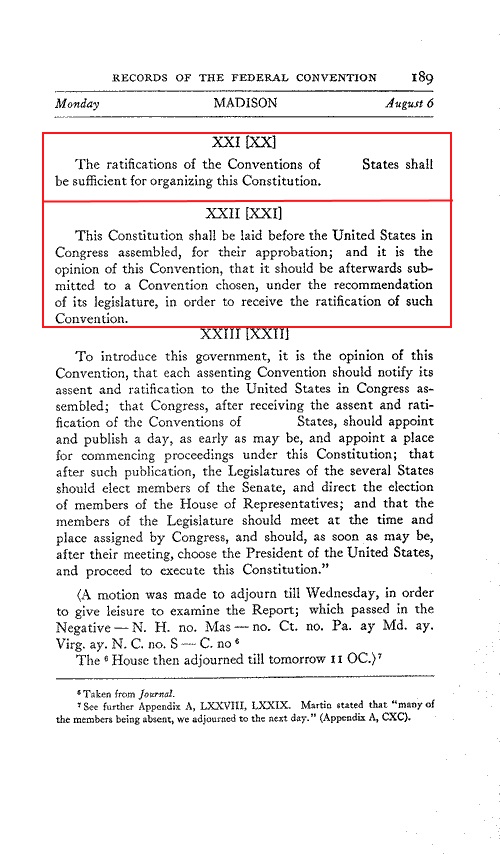

The

Committee of Detail proposals XXI [XX] and XXII [XXI] made it clear

elected conventions were to play a part in the ratification of the

Constitution as a whole

(see image left). As

before the Committee of Detail made no effort to distinguish between

the use of the word "convention" in the amendment proposal of XIX and

the use of the word "convention" in XXI leading to the conclusion they

were identical in all aspects only varying as to purpose, the former

limited to amendment of the Constitution, the latter limited to

ratification of the Constitution as a whole.

The

Committee of Detail proposals XXI [XX] and XXII [XXI] made it clear

elected conventions were to play a part in the ratification of the

Constitution as a whole

(see image left). As

before the Committee of Detail made no effort to distinguish between

the use of the word "convention" in the amendment proposal of XIX and

the use of the word "convention" in XXI leading to the conclusion they

were identical in all aspects only varying as to purpose, the former

limited to amendment of the Constitution, the latter limited to

ratification of the Constitution as a whole. The committee, by this time, had dropped any reference describing the fact conventions were representative bodies elected for the purpose of expressing "popular ratification" by the people (see image left). The committee's frequent revisions of their use in the amendment process indicates "popular ratification" conventions could either ratify an amendment proposal proposed by another political body (the state legislatures) or originate an amendment proposal without ratification by any other political body. The Committee of Detail's versions focused entirely on amendment "without the assent of the Nat'l Legislature" meaning Congress was a non-factor. None of the versions of amendment by the Committee of Detail even discussed Congress having any part in the amendment process other than calling the convention. The amendment process was thus left in the hands of two political groups: state legislatures and "popular ratification" conventions.

What part the convention and state legislatures played in the amendment process therefore was dependent on two factors: (1) the language describing the purpose and authority of the applications by the state legislatures and (2) the language describing the purpose and authority of the convention. In essence this language assigned one group the ability to amend the Constitution while simultaneously excluding the other group from this power. In all cases a convention was dependent on application by state legislature to cause it to be called by Congress. In no case did state legislatures have authority to call the convention themselves. This fact contradicts the belief of at least one convention advocacy group.

In the case of the committee's final report the purpose and authority of its application language permitted state legislatures to directly apply "for an amendment of this Constitution." In the final report the language describing the convention presumably defined the purpose of the convention to ratify the amendment already proposed by the state legislatures. Any other postulation makes the convention a needless redundancy.

Regardless of the mode of amendment proposal described by the Committee of Detail therefore, three criteria were established which would carry into the Constitution: (1) in all cases Congress calls the convention based on a numeric ratio of applications submitted by the state legislatures (thus the state legislatures, not Congress, determined whether a convention was mandated); (2) the purpose and authority of the application by the state legislatures is defined by the exact language within the amendment process: (3) the purpose and authority of the "popular ratification" convention is defined by the exact language within the amendment process.