The

Federal

Convention of 1787

Committee of the whole House operated from May 30 until June

19 at which time the committee "rose" and sent its report of

recommendations to the

convention for its consideration. The committee had concluded its work on

June 13 and issued its report. However the report was delayed until

June 19 by the submission of another plan by William Paterson of New

Jersey [State Attorney General New Jersey 1776-83; United States

Senator (NJ) 1789-90; Governor of New Jersey 1790-93: Associate Justice

United States Supreme Court 1793-1806] (image right) commonly referred to as the New

Jersey

plan.

The

Federal

Convention of 1787

Committee of the whole House operated from May 30 until June

19 at which time the committee "rose" and sent its report of

recommendations to the

convention for its consideration. The committee had concluded its work on

June 13 and issued its report. However the report was delayed until

June 19 by the submission of another plan by William Paterson of New

Jersey [State Attorney General New Jersey 1776-83; United States

Senator (NJ) 1789-90; Governor of New Jersey 1790-93: Associate Justice

United States Supreme Court 1793-1806] (image right) commonly referred to as the New

Jersey

plan. After six days of deliberation, the Committee of the whole House rejected the New Jersey plan. As noted in the convention Journal on June 19, "Mr. Gorham reported from the Committee that the Committee, having spent some time in the consideration of the propositions submitted to the House by the honorable Mr. Paterson--and of the resolutions heretofore reported from a Committee of the whole House, both of which had been to them referred, were prepared to report thereon -- and had directed him to report to the House that the Committee do not agree to the propositions offered by the honorable Mr. Paterson -- and that they again submit the resolutions, formerly reported, to the consideration of the House."

Robert's Rules of Order (11th Edition, pp.529-30) describes a Committee of the Whole as, "devices that enable the full assembly to give detailed consideration to a matter under conditions of freedom approximating those of a committee. Under each of these three procedures, [committee of the whole, quasi committee of the whole and informal consideration] any member can speak in debate on the main question or any amendment--for the same length of time as allowed by the assembly's rules--as often as he is able to get the floor. As under the regular rules of debate, however, he cannot speak another time on the same question so long as a member who has not spoken on it is seeking the floor.

Robert's Rules of Order discusses the difficulties of debate in a committee of the whole. "Each of these three devices is best suited to assemblies of a particular range in size and provides a different degree of protection against disorderliness and its possible consequences--which are risked when each member is allowed to speak an unlimited number of times in debate, such risks increasing in proportion to the size of the assembly. With respect to this type of protection, the essential distinctions between the three procedures may be summarized as follows:

In a committee of the whole, which is suited to large assemblies, the results of votes taken are not final decisions of the assembly, but have the status of recommendations which the assembly is given the opportunity to consider further and which it votes on finally under its regular rules. Also, a chairman of the committee of the whole is appointed and the regular presiding officer leaves the chair, so that, by being disengaged from any difficulties that may arise in the committee, he may be in a better position to preside effectively during the final consideration by the assembly."

The Advantages of a Committee of the whole House

The purpose of the Committee of the whole House was to "consider the state of the American Union." For the Federal Convention of 1787 this meant examining the problems associated with the Articles of Confederation. The committee's goal was to first define these problems then produce a series of recommendations intended to correct those deficiencies. Starting with Randolph's Virginia Plan, the convention took nearly a month to discuss and define the problems of the Articles of Confederation before creating a solution in the form of a new Constitution.

While the Constitution prohibits an Article V Convention from proposing a new Constitution, nothing prevents an Article V Convention of today from using the same methods of solution as did the Federal Convention of 1787. While the issues may be different, the purpose for a convention in our form of government remains unaltered; "to render the federal Constitution adequate to the exigencies of Government and preservation of the Union." An Article V Convention Committee of the whole House tasked to "consider the state of the American Union" offers the American people the chance to discuss and define the problems of this nation today just as the 1787 convention discussed and defined the problems of our nation then. Unlike Congress whose two house structure, differing rules and obstructive politics make creating a Committee of the whole House of Congress nearly impossible, the convention, being a single house, can easily turn itself into a Committee of the whole House just as the Federal Convention of 1787 did. The Committee of the whole House is an advantage frequently overlooked by convention proponents and opponents alike.

In our system of government elections are neither designed or intended to resolve the systematic problems of the state of the American Union. We do not give political leaders authority to unilaterally alter our form of government without due process of amendment. Thus our elected officials remain subject to the form of government that currently exists and cannot, without the due process of consent described in Article V, alter that form of government. Many problems of the American Union exist because the system of government somehow requires revision. Primarily, clauses in the Constitution have, over the years, been distorted beyond their original intention. A revision is thus mandated in order to correct the language to restore the original, limited intent or to define and limit the distortion. Congress, in many cases, is part of the problem.

Primarily for political reasons, Congress has failed to provide amendatory leadership either by proposing necessary amendments or obeying the Constitution and calling a convention when required thus allowing the amendment process to correct the problem created by actions in the government. The system of amendment is designed to be self correcting: some portion of the government distorts the constitutional plan; another part of the government corrects that distortion. Where permanent correction is required the amendment process is employed. Only by amendment can systematic problems of the government be permanently solved. In order to find what the American people believes need to be corrected in the American system of government requires the governmental body first ask the question then listen for the answer.

Thanks to the Internet the Committee of the whole House can, through direct public discourse with the American people, listen to what the American people believe are the problems of this nation and what they recommend as solutions to those issues. The convention can be even more effective today than the convention of 1787 was in repairing problems with the system of American government. For the most part the 1787 convention had to assume what the American people wanted in its new form of government because it was impossible to communicate with them directly during the convention. This is not true today. While the convention delegates most assuredly will be presenting views obtained during their recent elections, the committee has the added advantage of being able to obtain input from the American people in real time during the convention as well.

Normally the only time the "state of the American Union" is "discussed" is during an election cycle. That time however is not spent in thoughtful discourse however. Instead the "discussion" is framed in baseless accusations, attack ads and the like designed not to actually "consider the state of the American Union" but to convince the American voter if he votes for a particular candidate all problems of the American Union will be solved, which of course, they never are. The Committee of the whole House gives the American people an independent platform unfettered from the usual political battle associated with elections.

The committee provides a means whereby delegates listen while the American people speak without the usual filters of pundits, mass media, special interests and so forth "interpreting" that message. The American people are the source of all sovereignty in this nation. The committee offers the sovereign the opportunity to express its collective mind directly to its representatives as part of the convention process on recommendations it believes are necessary to correct the deficiencies in the American Union. The more the American public is allowed to participate in the decisions of the convention, the more that public will believe in the system of amendment created by the convention of 1787.

The committee can create formal Internet forums of different purposes designed to listen to the American people. These forums can be held (1) convention wide, (2) by state delegation or (3) by individual delegate during the period of the Committee of the whole House. The convention can establish a forum, for example, to solicit recommendations for proposed amendments directly from the people. For those who lacking Internet access, a simple mailing address (with appropriate rules for submission such as type font, length, content and so forth) coupled with scanning received letters resolves any issue of citizen access. Appropriate rules (such as mandating real names and addresses for participants rather than pseudonyms, allowing one comment per citizen and limiting the length of a comment to only the text of the proposed amendment) will keep the forums on track.

Congress has no such formal forums. It does not listen. Anyone attempting to contact a member of Congress knows unless they are a special interest they are always deflected by staff and rarely speak directly to their representative. Any response received from a member of Congress is generally a meaningless form letter thanking the person "for expressing his views" and saying the member of Congress will "take them into account." The primary focus of Congress is passage of legislation intended to advance political agenda or career.

Because the view of the Article V Convention long term however, it can (indeed must) take time to discuss the "state of the American Union" as the Federal Convention of 1787 did. Thus the convention can create the necessary and proper amendments needed to resolve the issues of today in the American Union. Long after the current political agendas have faded and current politicians died, the effect of an amendment remains. This fact mandates the convention "get it right" meaning having the support of the American people in the decisions made by the convention which the Committee of the whole House accomplishes.

This opportunity for discussing the "state of the American Union" however is only afforded to the American people in an "open" "numeric" convention. A "same subject" "closed" convention does not require consideration of the state of the American Union with the participation of the American people. The "state of the American Union" has been pre-determined in a "same subject" "closed" convention by the various state legislatures and special interests who have already reached their decision. There is no reason to consult the American people for their opinion as it has already been made for them.

The Events of the 1787 Committee of the whole House

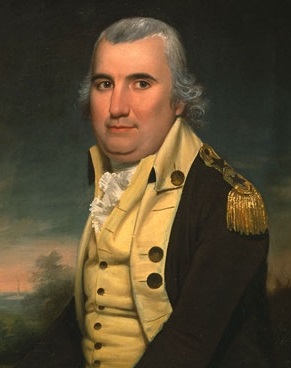

The

Committee of the whole House was chaired by

Nathaniel Gorham [Delegate Continental Congress 1782-83; 1785-87 (MA);

President of Continental Congress, 6 June 1786 to 5 November 1786,

delegate to Federal Convention of 1787] (image right). The committee examined each of

Randolph's proposals, discussed them and revised the wording. The committee created a report of recommendations

for needed changes to the national government. The report was then

referred back to the convention for its consideration. The report of

the Committee of the whole House was printed on June 13. The

committee then considered other plans submitted by other convention

delegates. These were rejected by the Committee of the whole House. The committee finally adjourned on June 19.

The

Committee of the whole House was chaired by

Nathaniel Gorham [Delegate Continental Congress 1782-83; 1785-87 (MA);

President of Continental Congress, 6 June 1786 to 5 November 1786,

delegate to Federal Convention of 1787] (image right). The committee examined each of

Randolph's proposals, discussed them and revised the wording. The committee created a report of recommendations

for needed changes to the national government. The report was then

referred back to the convention for its consideration. The report of

the Committee of the whole House was printed on June 13. The

committee then considered other plans submitted by other convention

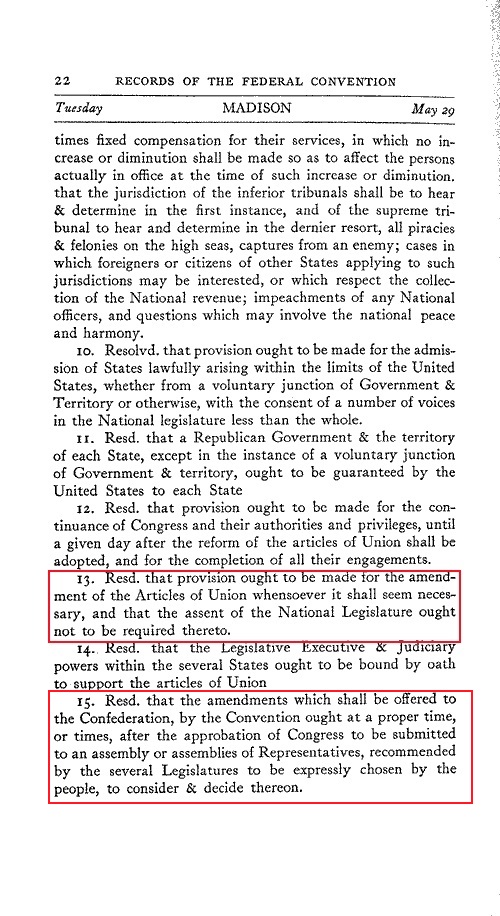

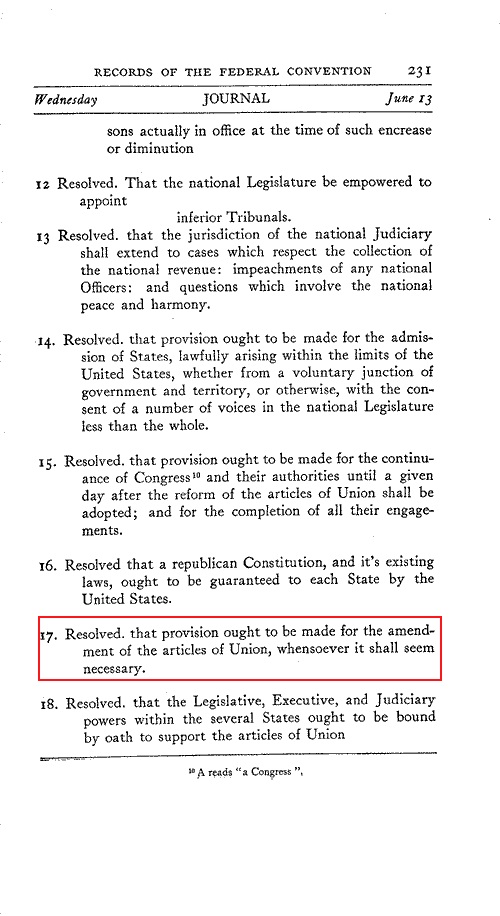

delegates. These were rejected by the Committee of the whole House. The committee finally adjourned on June 19. Even thought not initially mentioned in his thirteenth proposal, ("Resd. that provision ought to be made for the amendment of the

Articles of Union whensoever it shall seem necessary, and that the

assent of the National Legislature ought not to be required thereto.") Randolph's proposal ultimately created to two

conventions in the Constitution, the convention for proposing

amendments and the state ratification convention. This, in addition to

a third convention created by his fifteenth proposal ("Resd. that the amendment which shall be

offered to the Confederation, by the Convention ought at a proper time,

or times, after the approbation of Congress to be submitted to an

assembly or assemblies of Representatives, recommended by the several

Legislatures to be expressly chosen by the people, to consider &

decide thereon.").

Even thought not initially mentioned in his thirteenth proposal, ("Resd. that provision ought to be made for the amendment of the

Articles of Union whensoever it shall seem necessary, and that the

assent of the National Legislature ought not to be required thereto.") Randolph's proposal ultimately created to two

conventions in the Constitution, the convention for proposing

amendments and the state ratification convention. This, in addition to

a third convention created by his fifteenth proposal ("Resd. that the amendment which shall be

offered to the Confederation, by the Convention ought at a proper time,

or times, after the approbation of Congress to be submitted to an

assembly or assemblies of Representatives, recommended by the several

Legislatures to be expressly chosen by the people, to consider &

decide thereon."). Thus the convention as part of the constitutional system of government was recognized from the very start of the process used to create the Constitution. This is unsurprising given the Constitution was created by a convention. The number of times the framers of the Constitution placed the convention into the Constitution leads to one conclusion; the framers not only believed in the value of the convention as part of the constitutional system of government but its need as providing a means whereby the people affirmatively exercised their sovereignty. The text of the resolutions (image left) as published in Farrand may be clicked to enlarge.

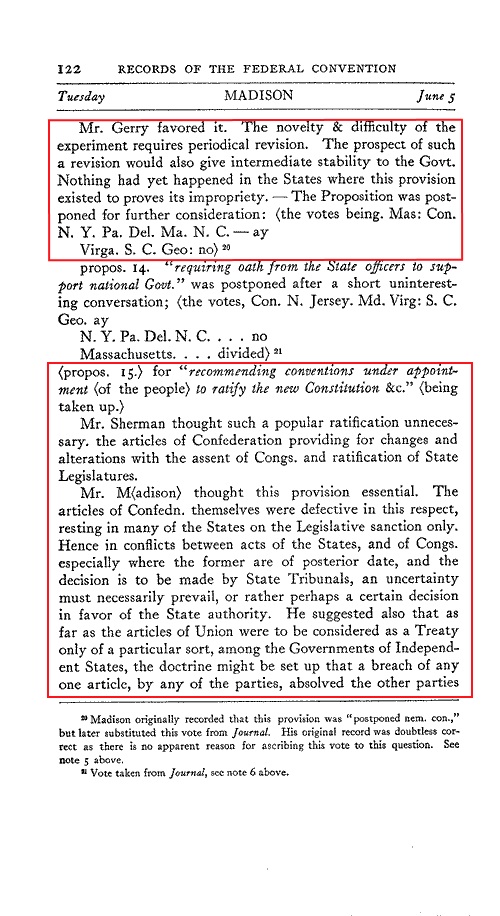

The convention generally discussed Randolph's proposals in order of proposition. The amendment proposal, (the thirteenth) was not discussed until Tuesday, June 5. The proposal called for a process of amendment independent of Congress but specified no means to accomplish this. On the same day the convention also discussed the fifteenth proposal, ratification of the convention's proposals by elected conventions in the various states. As events later proved the reasoning applied to that discussion paralleled the reasoning applied to the amendment process called for in the thirteenth proposal.

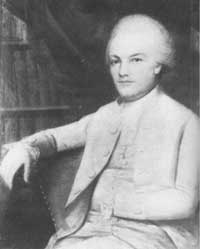

Two related delegates (first cousins), both representing South Carolina attended the convention. These were Charles Pinckney (often

misspelled in Madison's notes as "Pinkney") and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, [United States

Minister to France 1796-97] (image left). Charles

Pinckney [member South Carolina House of

Representatives 1792-96, 1810-14; member South Carolina Senate 1779-82;

President of South Carolina Senate 1779-82; Member Confederation

Congress 1784-87; United States Senator (SC) 1798-1801; United States

Minister to Spain 1802-04; member House of Representatives (SC)

1819-21; Governor of South Carolina 1789-92, 1796-98, 1806-08] spoke on the amendment issue of Proposition 13 on June 5 (image right). In order to distinguish the two cousins Charles Cotesworth was referred to as

"C.C." Pinckney in the convention Journal. FOAVC will follow the same notation as that of the convention Journal.

Two related delegates (first cousins), both representing South Carolina attended the convention. These were Charles Pinckney (often

misspelled in Madison's notes as "Pinkney") and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, [United States

Minister to France 1796-97] (image left). Charles

Pinckney [member South Carolina House of

Representatives 1792-96, 1810-14; member South Carolina Senate 1779-82;

President of South Carolina Senate 1779-82; Member Confederation

Congress 1784-87; United States Senator (SC) 1798-1801; United States

Minister to Spain 1802-04; member House of Representatives (SC)

1819-21; Governor of South Carolina 1789-92, 1796-98, 1806-08] spoke on the amendment issue of Proposition 13 on June 5 (image right). In order to distinguish the two cousins Charles Cotesworth was referred to as

"C.C." Pinckney in the convention Journal. FOAVC will follow the same notation as that of the convention Journal.

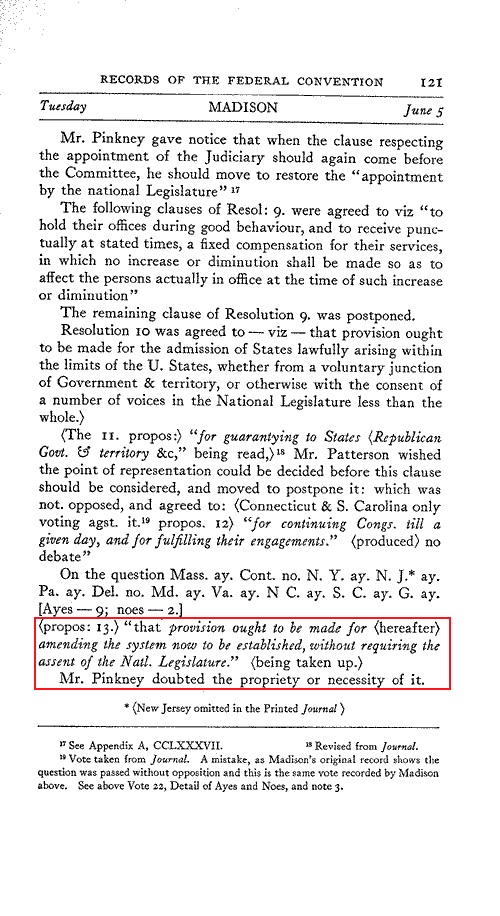

The June 5 discussion of Proposition 13 was brief.

(Click images left to enlarge). Charles

Pinckney stated he "doubted the

propriety or necessity of it" meaning Pinckney believed an amendment

process unnecessary. Elbridge Gerry,[member of Congress (MA) 1789-93;

Governor of Massachusetts, 1810-12; Vice President of the United

States, 1813-14]

(image right) "favored it" saying, "The novelty & difficulty of the

experiment requires periodical revision. The prospect of such a

revision would also give intermediate stability to the Govt. Nothing

had yet happened in the States where this provision existed to proves

its impropriety."

The June 5 discussion of Proposition 13 was brief.

(Click images left to enlarge). Charles

Pinckney stated he "doubted the

propriety or necessity of it" meaning Pinckney believed an amendment

process unnecessary. Elbridge Gerry,[member of Congress (MA) 1789-93;

Governor of Massachusetts, 1810-12; Vice President of the United

States, 1813-14]

(image right) "favored it" saying, "The novelty & difficulty of the

experiment requires periodical revision. The prospect of such a

revision would also give intermediate stability to the Govt. Nothing

had yet happened in the States where this provision existed to proves

its impropriety." Following these comments, the proposition passed its first hurdle. It was postponed for further discussion by a vote of seven states to three. Thus the convention accepted the concept the future Constitution must have a system of amendment to provide for "periodical revision." Had the convention agreed with Pinckney's sentiment of no necessity for amendment of the Constitution and removed Randolph's provision the entire history of the United States would be different. Had the unanimous consent required in the Articles of Confederation remained in place thus allowing a single state to control the destiny of this nation, it is almost certain the states would have eventually gone their separate ways.

Following

a "short uninteresting conversation" regarding Proposition 14 (also

postponed for further discussion) the convention began discussion of

Proposition 15, "recommending conventions under appointment <of the

people> to ratify the new Constitution &c." The full comments by

the various delegates can be read in the panels above. The comments of

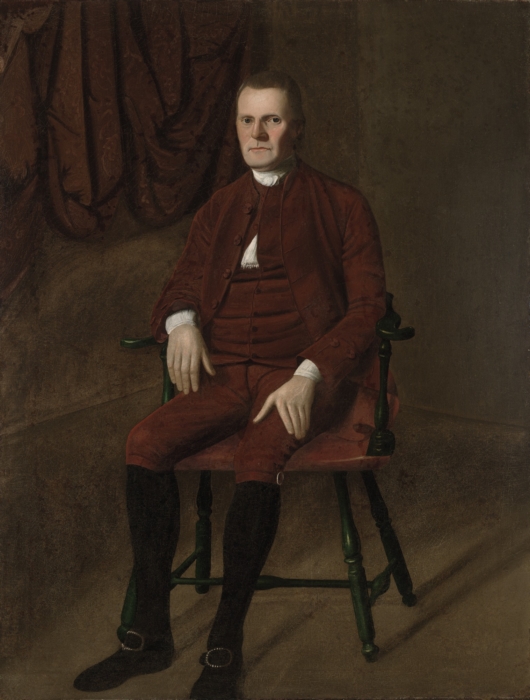

Roger Sherman [only person to have signed the Continental Association

(1774), Declaration of Independence (1776), Articles of Confederation

(1781), Constitution (1787), authored the "Great Compromise"

creating bicameral Congress resolving the greatest obstacle to

the creation of the Constitution, delegate to Continental Congress,

1774-81, 1784-84; member House of Representatives (CT) 1789-91; United

States Senator (CT) 1791-93] (image right) make it clear he and

the other delegates understood the difference between "popular

ratification" (ratification by representatives of the people) in a

convention and ratification by the state legislatures.

Following

a "short uninteresting conversation" regarding Proposition 14 (also

postponed for further discussion) the convention began discussion of

Proposition 15, "recommending conventions under appointment <of the

people> to ratify the new Constitution &c." The full comments by

the various delegates can be read in the panels above. The comments of

Roger Sherman [only person to have signed the Continental Association

(1774), Declaration of Independence (1776), Articles of Confederation

(1781), Constitution (1787), authored the "Great Compromise"

creating bicameral Congress resolving the greatest obstacle to

the creation of the Constitution, delegate to Continental Congress,

1774-81, 1784-84; member House of Representatives (CT) 1789-91; United

States Senator (CT) 1791-93] (image right) make it clear he and

the other delegates understood the difference between "popular

ratification" (ratification by representatives of the people) in a

convention and ratification by the state legislatures. While the thinking of the delegates on the question of ratification was clearly divided one point was evident: the delegates understood ratification by convention meant ratification by the people. Ratification by state legislature meant ratification by state legislature. Each mode was accepted as conclusive to accomplish the purpose. Nothing indicates the delegates believed a convention was to be controlled by the state legislature thus allow the legislature to control both methods of ratification or proposal. Proposition 15 was postponed for further discussion.

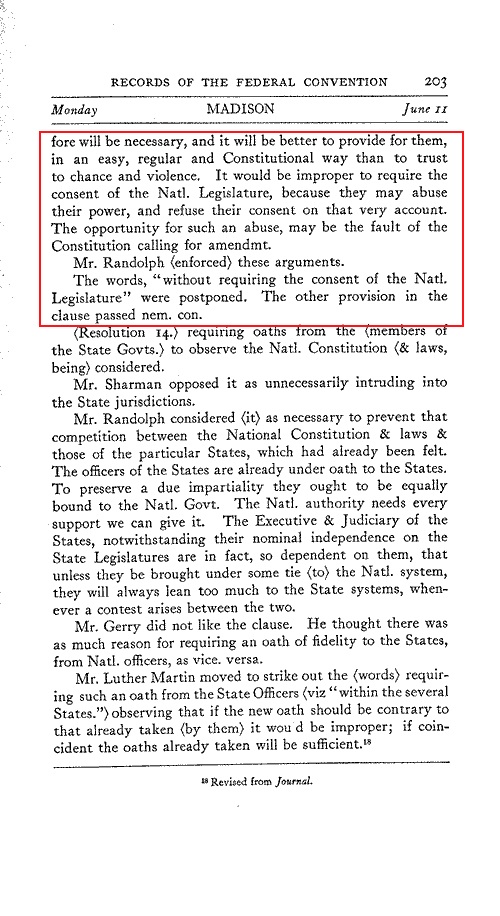

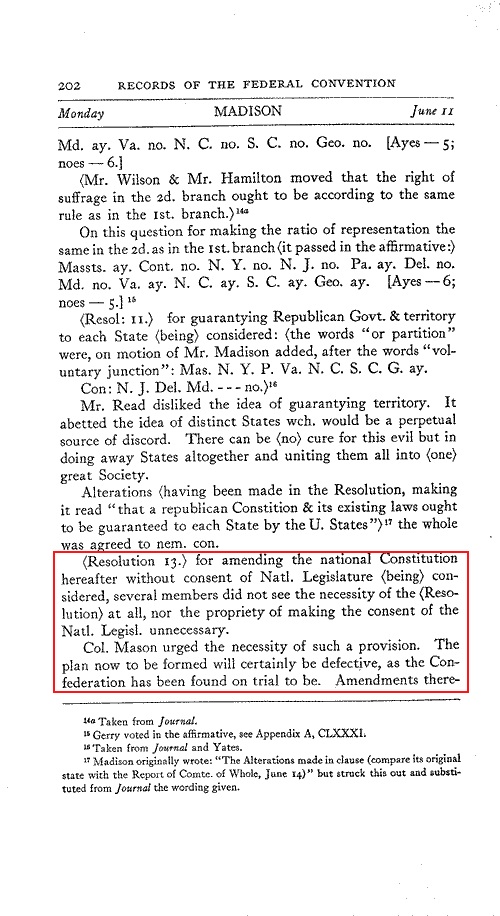

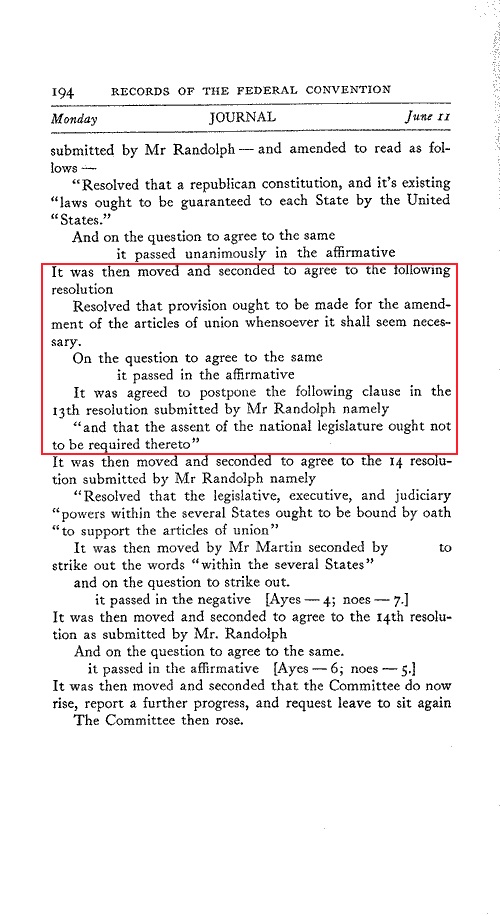

The

matter of the amendment described in Proposition 13 was again taken up

by the committee on June 11. At this time, the convention voted to

accept the first portion of Randolph's proposal, "Resolved that

provision ought to be made for the amendment of the articles of union

whensoever it shall seem necessary..." but then voted to "postpone the

following clause in the 13th resolution submitted by Mr. Randolph

namely "and that the assent of the national legislature ought not to be

required thereto." At this time George Mason (referred to as Col. Mason

in the convention Journal) [Mason held no national office in his

lifetime but was a member of the Virginia state legislature on several

occasions and helped write the Virginia Constitution of 1776] (image left) first

spoke on the matter of amendment.

The

matter of the amendment described in Proposition 13 was again taken up

by the committee on June 11. At this time, the convention voted to

accept the first portion of Randolph's proposal, "Resolved that

provision ought to be made for the amendment of the articles of union

whensoever it shall seem necessary..." but then voted to "postpone the

following clause in the 13th resolution submitted by Mr. Randolph

namely "and that the assent of the national legislature ought not to be

required thereto." At this time George Mason (referred to as Col. Mason

in the convention Journal) [Mason held no national office in his

lifetime but was a member of the Virginia state legislature on several

occasions and helped write the Virginia Constitution of 1776] (image left) first

spoke on the matter of amendment. Mason was to make similar comments which ultimately led to the Gerry amendment inserting the convention clause in the final version of Article V. Mason "urged the necessity of such a provision." Mason said, "The plan now to be formed will certainly be defective, as the Confederation has been found on trial to be. Amendments therefore will be necessary, and it will be better to provide for them, in an easy, regular and Constitutional way than to trust to chance and violence. It would be improper to require the consent of the Natl. Legislature, because they may abuse their power, and refuse their consent on that very account. [Emphasis added]. The opportunity for such an abuse, may be the fault of the Constitution calling for amendmt." Click images right to enlarge.

The Committee of the whole House released its final report of recommendations to the convention on June 13. While the recommendations would undergo numerous further changes they served as the framework for what would become the Constitution. In just under a month the delegates had defined the problems of the "American Union" in concrete terms and described solutions for those problems. In most instances Randolph's original language had been heavily reworked and expanded to include a more comprehensive description than had originally been submitted. The original 15 proposals, now numbering 19 designated the amendment proposal as Proposition 17.

The need for amendment was firmly established and accepted by the convention. While the clause allowing for amendment without consent of the National Legislature had been removed, these were simply recommendations and thus subject to further discussion. The committee had already determined on June 11 (recommending postponing discussion on the clause) that it would return to the question of amendment without national legislative consent. The final report of the Committee of the whole House may be read below by clicking the images to enlarge them.

|

|

|

|

|

Proof the delegates of the 1787 convention understood a convention and state legislature were autonomous of each other is shown by the fact that in the end three separate conventions were created in the Constitution. The first was the ratification conventions described in Article VII used to ratify the Constitution as a whole. The second are the state ratification conventions described in Article V used to ratify a proposed amendment. The third is the convention for proposing amendments described in Article V.

Neither the language of the Article VII or Article V stipulate conventions are regulated by state legislatures. This is particularly significant in discussing a convention for proposing amendments. The meaning of the word as understood by the Founders in their discussion of a convention proves that wherever inserted in the Constitution the word "convention" meant election of delegates representing the people who, in turn, then determined the question or questions before them as defined by the purpose described in the Constitution. The Founders used the words "popular ratification" to describe the process of a convention.

Had the Founders intended for the convention to propose amendments to operate differently than by "popular ratification" then it was incumbent on them to describe this difference in their language in order to distinguish that form of convention (one controlled by state legislature) from the other two "popular ratification" conventions (not controlled by state legislature) described in the Constitution. This is particularly true given one of the two "popular ratification" conventions was described in the same sentence as the convention for proposing amendments. The rules of English grammar (not to mention common sense) demand if two different meanings are attached to the same word used twice in the same sentence, then the words of that sentence must reflect this fact. Otherwise it is assumed the two identical words are to be interpreted as being identical in meaning and intent.

History records show in all instances where the conventions described in the Constitution have been used, those conventions operated by means of "popular ratification" rather than by control of the state legislatures. It appears the convention delegates of 1787 so associated the word "convention" with "popular ratification" they saw no reason to include a description of that fact in the Constitution. The fact was simply understood by all at the time including the state legislatures who created the laws creating the elected ratification conventions between 1788-90.

The relation of "convention" and "popular ratification" being autonomous of the state legislature was obviously was understood again when, 200 years later, Congress designated the state ratification convention as the mode of ratification for the 21st Amendment. In response, state legislatures created laws establishing elected conventions to execute the task of ratification. The state legislatures did not attempt to regulate these conventions and thus determine the outcome of the ratification votes. The 21st Amendment was thus ratified by "popular ratification."

From the beginning of the 1787 convention it was understood a convention was not controlled by legislature but by the people. If this were not true, the convention delegates of 1787 created language establishing two modes of ratification which, in fact, are a single mode controlled by state legislature. Such is not the case. The fact the word "convention" as used in the Constitution refers to "popular ratification" (which was executed by state legislatures and Congress in events 200 years apart without any attempt at control) is conclusive evidence the 1787 convention delegates, who were quite capable of describing amendment proposal by state legislature without a convention, intended the third convention, a convention for proposing amendments (now popularly referred to as an Article V Convention), to be a form of "popular ratification." There is no record of the delegates even discussing the possibility that any of the conventions described in the Constitution were to be a "convention of the states." That term no only does not exist in the Constitution, but was never even contemplated by the 1787 Convention.

In the various plans of amendment discussed during the convention the purpose of the convention, if it did not propose, was to ratify. This was done in order to prevent amendment of the Constitution by the legislatures without consent of the people. If an Article V Convention is controlled by legislature then, under the structure of our Constitution, it is possible for proposal of an amendment by legislatures without the proposal ever being reviewed by the people or Congress. Such an event occurred in September, 2016. This form of government is advocated by at least one "same subject" "closed" convention group. With the convention as a form of "popular ratification" however the functional sovereignty of the people is assured.

This fact of functional sovereignty of the people is ignored by those favoring a "same subject" "closed" convention. In the amendment versions of the 1787 convention, one fact stands out: unless it is assumed the convention is controlled by the people as a form of "popular ratification" the convention serves no constitutional purpose whatsoever and therefore is redundant. The early drafts of Article V (for the most part) required a ratification convention with state legislatures proposing the amendment. The final draft of Article V assigned the power of amendment proposal to the convention instead of the state legislatures. Thus in our form of government, the convention, not the state legislatures, propose amendments.

If the 1787 convention intended a convention be controlled by state legislature, holding the convention to "propose" the amendment makes no sense. Under the structure of amendment described in the various amendment plans discussed in 1787, the proposed amendment, having already been agreed to by the legislatures, did not require a convention to execute the proposed amendment. The only logical purpose for convention then was to express "popular ratification" for the amendment by the people. Were this not true the amendment proposal containing the precise language of the amendment could simply have been circulated among the various legislature until the necessary consent was obtained then forwarded to Congress for final enrollment without ever involving a convention.Thus inserting a convention into the amendment process meant, at that moment in the process whether it be proposal or ratification, "popular ratification" by the people was to occur independent of the state legislatures.

This form of "popular ratification" ensures the fundamental principle of this nation: sovereignty resides with the people. Often overlooked today by many Americans is the fact when the Founders said the American people were sovereign they meant it in the literal, not symbolic, sense. The people were therefore given a means to exercise that sovereignty directly. The people can therefore propose amendments directly through "popular ratification" or ratify proposals created by other political bodies by means of "popular ratification."

Not only did the Founders create a system whereby amendments to the Constitution can be proposed and ratified by Congress and state legislature but also independently of Congress and legislature as well. Through the use of an Article V Convention and state ratification conventions the people can revise the Constitution without consent of either Congress or state legislature. Yet their power is not unlimited; it still requires application by state legislature and designation by Congress to accomplish this sovereign decision. The sovereign power is therefore limited by the separation of powers concept running throughout the Constitution.