Thus the Framers of the Constitution were quite capable of describing amendment proposal for the Constitution by state legislatures in plain and unequivocal language requiring no implication, speculation, rules of construction, interpolation or addition in order to "understand" their intention if that were their intention. It is reasonable therefore to state had the Founders intended state legislatures have authority to propose amendments by means of a convention which they controlled in regards to agenda and product, the language of the Constitution would clearly have reflected this intent. Similarly, if the Founders intended state legislatures possessed the authority to directly amend the Constitution, that language would be equally plain and unequivocal.

The Court stated, "If the framers of the instrument had any thought that amendments differing in purpose should be ratified in different ways, nothing would have been simpler that so to phrase article 5 as to exclude implication or speculation. The fact that an instrument drawn with such meticulous care and by men who so well understood now to make language fit their thought does not contain any such limiting phrase affecting the exercise of discretion by the Congress in choosing one or the other alternative mode of ratification is persuasive evidence that no qualification was intended."

Equally important to this discussion is the Court's comment in Hawke v Smith, 253 U.S. 221, 228 (1920) in which the Court said, "There can be no question that the framers of the Constitution clearly understood and carefully used the terms in which that instrument referred to the action of the Legislatures of the states. When they intended that direct action by the people should be had they were no less accurate in the use of apt phraseology to carry out such purpose." (See Page 17 G).

*****

As previously discussed Farrand published his seminal work, "The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 in a three volume set in 1911. In 1937 Farrand released a revised edition of his 1911 work with the publication of a fourth volume. As stated in the volume's preface, "The controlling purpose in preparing the original edition of The Records of the Federal Convention (New Haven, 1911) was to gather in convenient and reliable form every scrap of information accessible upon the drafting of the Constitution of the United States. Errors were inevitable in a work embodying numerous documents, of diverse character, derived from scattered sources. Mistakes whenever discovered, if they were of any significance, were correct in subsequent printings. The obvious course would have been to incorporate also in those reprintings new material as it came to light, but, owing to the plan adopted of grouping together all the different records of each day's sessions, the insertion of new items at their proper places would have involved the recasting of plates for many pages, and sometimes would have meant the repaging of entire volumes. Not a few lawyers and even members of the Federal Supreme Court have expressed the hope that the page numbering of the first printing might be retained for convenience in identifying references. ... Instead of attempting to incorporate the new items in their several places, it has been decided to issue a fourth, supplementary volume."

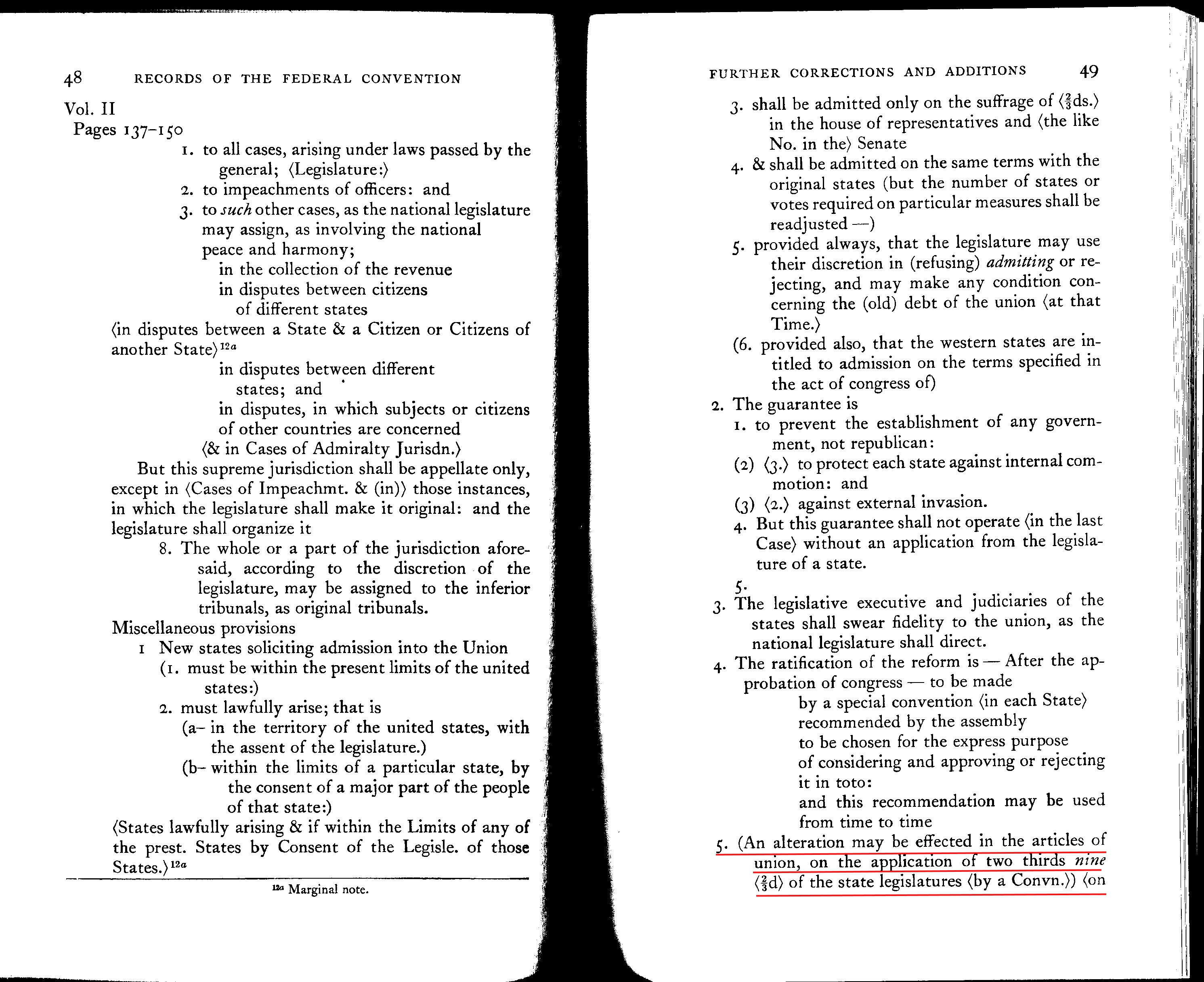

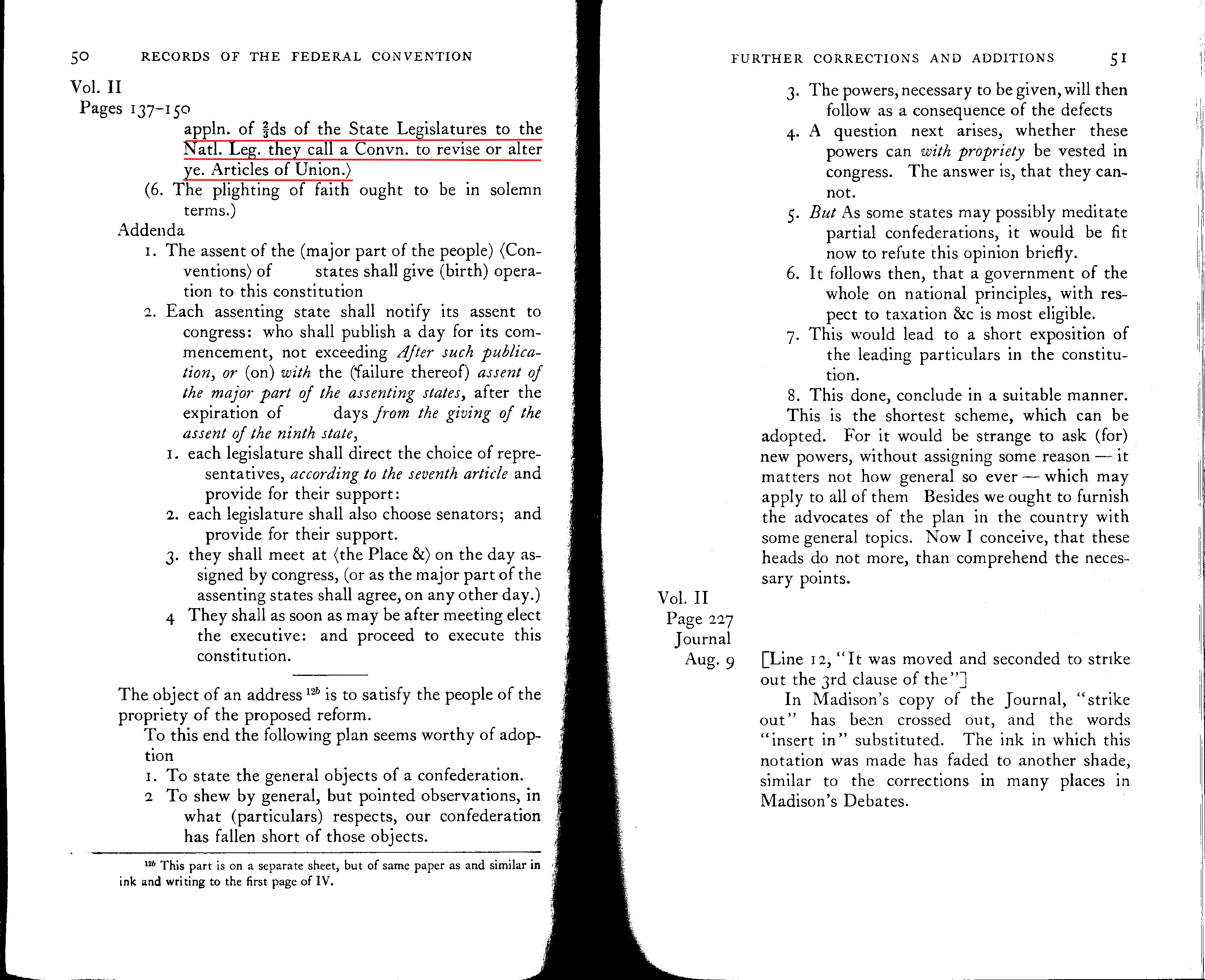

FOAVC therefore begins its presentation by presenting the supplemental material in Volume IV of Farrand related to Article V. All images of pages presented throughout this presentation may be clicked on to enlarge. Text is highlighted as required. There are only two supplements presented by Farrand related to Article V but which FOAVC are quite significant in the discussion of the intent of Article V. They are not corrections to previously published text but are incorporated with corrections of text to other parts of the 1911 publication. As stated Farrand chose not to insert these corrections into the original text. Therefore the corrections are simply listed by volume and page leaving the reader the task to "add" them.

The

first supplement referring to the amendment process recorded by Farrand

is found on pages 49-50 of Volume IV (left panels) and refers to notes

of the Committee of Detail found in Volume II. The second supplement

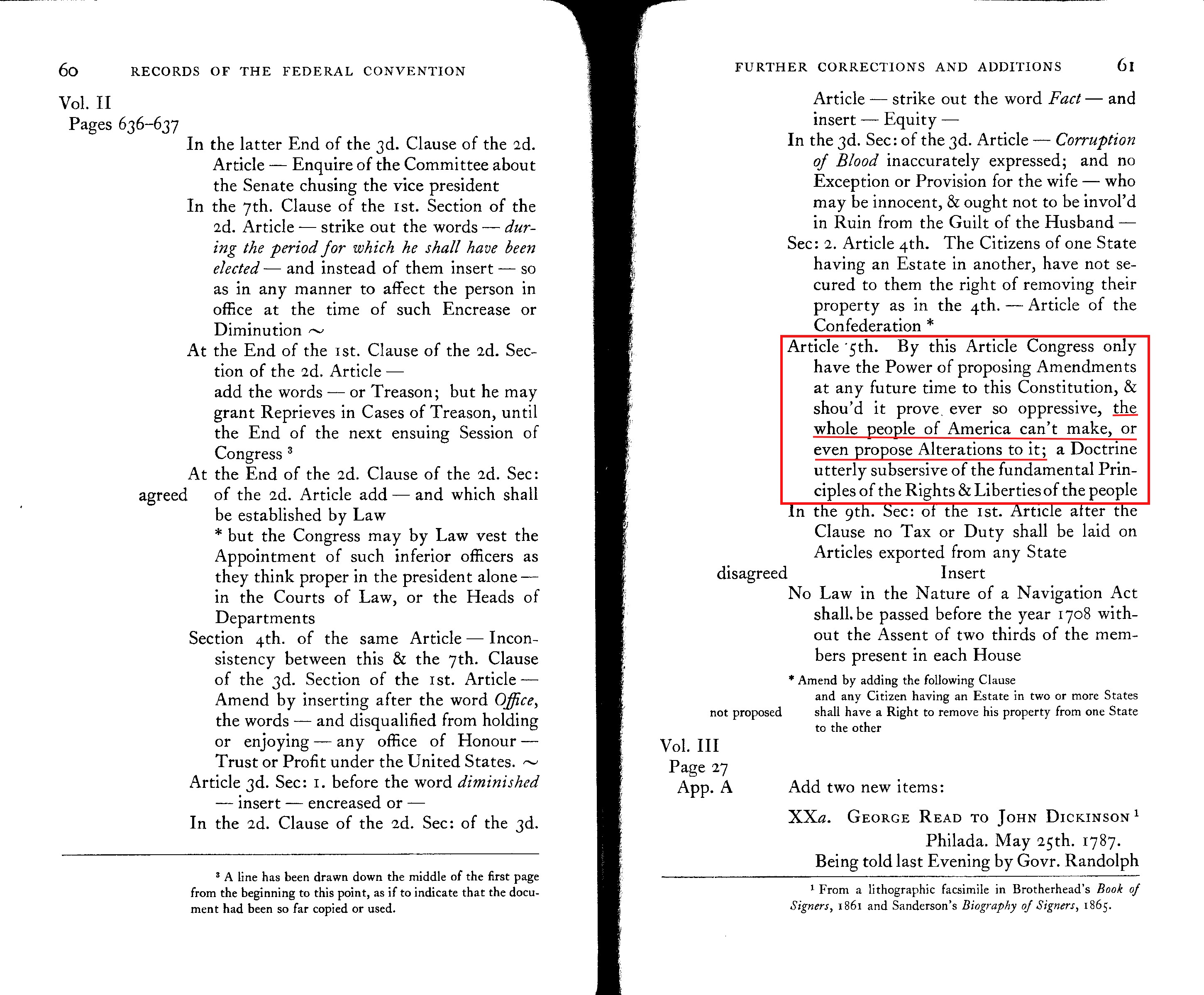

page 61, (right panel) again referring to Volume II, pages 636-37, adds

written notes made by George Mason on his copy of the September 12th

draft of the Constitution. The significance of statement between the two

supplements is clear. In the earlier Committee of Detail report, it is

clear the state legislatures could amend the Constitution, "(An alteration may be effecting in the articles of the union, on the application of two thirds nine

<2/3d> of the state legislatures <by a Convn.>) <on

appln. of 2/3ds of the State Legislatures to the Natl. Leg. they call a

Convn. to revise or alter ye. Articles of Union.>"

The

first supplement referring to the amendment process recorded by Farrand

is found on pages 49-50 of Volume IV (left panels) and refers to notes

of the Committee of Detail found in Volume II. The second supplement

page 61, (right panel) again referring to Volume II, pages 636-37, adds

written notes made by George Mason on his copy of the September 12th

draft of the Constitution. The significance of statement between the two

supplements is clear. In the earlier Committee of Detail report, it is

clear the state legislatures could amend the Constitution, "(An alteration may be effecting in the articles of the union, on the application of two thirds nine

<2/3d> of the state legislatures <by a Convn.>) <on

appln. of 2/3ds of the State Legislatures to the Natl. Leg. they call a

Convn. to revise or alter ye. Articles of Union.>" However by the time of Mason's comments of September 12, it is clearly the people who are empowered to amend the Constitution. Mason makes no mention of the state legislatures being deprived of the right to "revise or alter" the Constitution. "Article 5th. By the Article Congress only have the Power of proposing Amendments at any future time to this Constitution, & shou'd it prove ever so oppressive, the whole people of America can't make, or even propose Alterations to it; a Doctrine utterly subsersive of the fundamental Principles of the Rights & Liberties of the people." [Emphasis added]. This change in language cannot be dismissed. If Mason had intended to mean the state legislatures could not propose alterations, he certainly would have stated that in his notes rather than language referring to depriving the people of their right to "revise or alter" the Constitution.

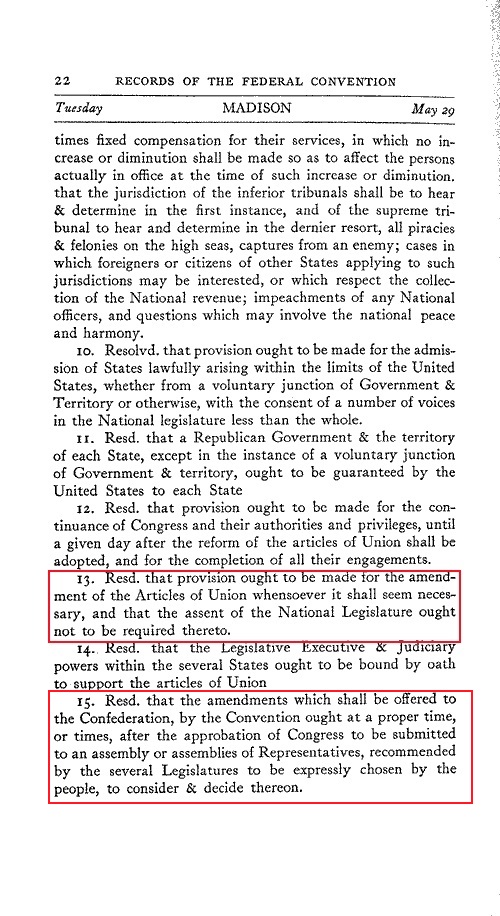

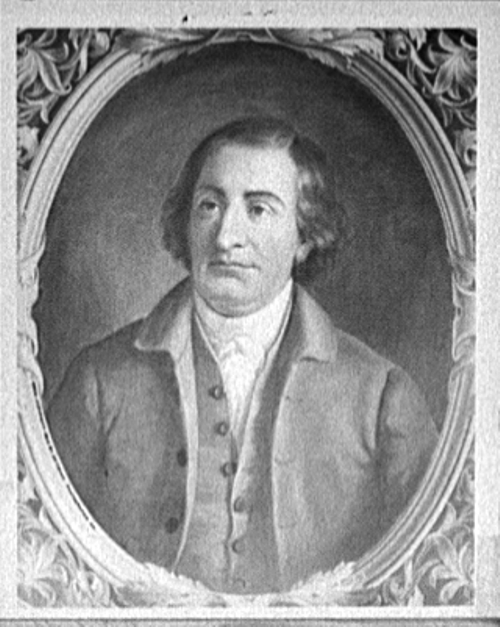

As

with much of the Constitution Article V had its beginnings as one of

the provisions in what is generally referred to as the Virginia Plan.

Of all the various plans of government presented by various delegates

to the convention, the Virginia Plan is probably the most

comprehensive. The Virginia Plan was presented to the convention on May

29 by Edmund

Randolph of Virginia [member Continental Congress

1779-82; Governor of Virginia, 1786-88; delegate to Federal Convention

of 1787, member of Committee of Detail; delegate to Virginia

Ratification Convention 1788; United States Attorney General 1789-94;

United States Secretary of State 1794-95].

As

with much of the Constitution Article V had its beginnings as one of

the provisions in what is generally referred to as the Virginia Plan.

Of all the various plans of government presented by various delegates

to the convention, the Virginia Plan is probably the most

comprehensive. The Virginia Plan was presented to the convention on May

29 by Edmund

Randolph of Virginia [member Continental Congress

1779-82; Governor of Virginia, 1786-88; delegate to Federal Convention

of 1787, member of Committee of Detail; delegate to Virginia

Ratification Convention 1788; United States Attorney General 1789-94;

United States Secretary of State 1794-95].