On

May 5, 1789,

after Congressman Theodorick Bland (VA) introduced the first state

application in U.S. history for an Article V Convention to Congress, he

moved to refer his state's application to the

Committee of the Whole on the state of the Union. The House then discussed how

Congress should deal all state applications specifically

whether the applications should be referred to any congressional

committee and if not, why not. Ultimately the House created a policy

for recording state applications for a convention call (later agreed to

in the Senate) which has remained unchanged

since 1789.

On

May 5, 1789,

after Congressman Theodorick Bland (VA) introduced the first state

application in U.S. history for an Article V Convention to Congress, he

moved to refer his state's application to the

Committee of the Whole on the state of the Union. The House then discussed how

Congress should deal all state applications specifically

whether the applications should be referred to any congressional

committee and if not, why not. Ultimately the House created a policy

for recording state applications for a convention call (later agreed to

in the Senate) which has remained unchanged

since 1789. During the discussion the terms and conditions for a convention call was discussed by the members of the House. This included James Madison, who wrote the text of Article V at the 1787 Convention and Elbridge Gerry whose motion at the 1787 Convention inserted the convention clause into Madison's text which ultimately became the final language of Article V. The images of the Virginia application and the subsequent discussion can be read at left by clicking the images. The discussion is reproduced below with images of the various participants and a brief biography of each.

*****

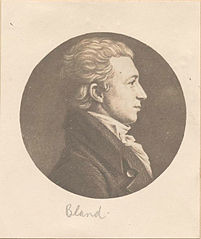

"After the reading of this application, Mr. BLAND [Theodorick Bland, member Confederation Congress 1780-83; member House of Representatives (VA) 1789-90] moved to refer it [the Virginia application] to the Committee of the whole on the state of the Union.

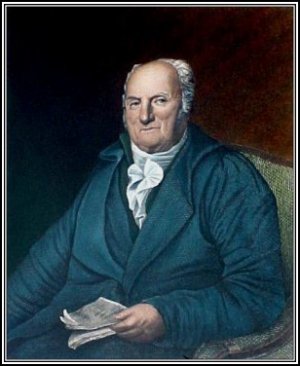

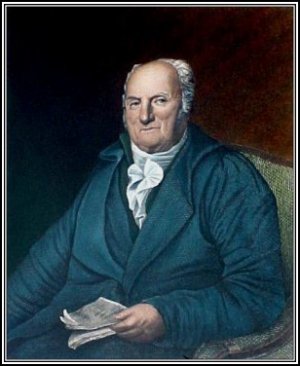

Mr. BOUDINOT: [Elias Boudinot, President Confederation Congress 1782-83; member House of Representatives (NJ) 1789-95; Director

United States Mint 1797-1805] According to the terms of the

Constitution, the business cannot be taken up until a certain number of

States have concurred in similar applications; certainly the House is

disposed to pay a proper attention to the application of so respectable

a State as Virginia, but if it is a business which we cannot interfere

with in a constitutional manner, we had better let it remain on the

files of the House until the proper number of applications come

forward."

Mr. BOUDINOT: [Elias Boudinot, President Confederation Congress 1782-83; member House of Representatives (NJ) 1789-95; Director

United States Mint 1797-1805] According to the terms of the

Constitution, the business cannot be taken up until a certain number of

States have concurred in similar applications; certainly the House is

disposed to pay a proper attention to the application of so respectable

a State as Virginia, but if it is a business which we cannot interfere

with in a constitutional manner, we had better let it remain on the

files of the House until the proper number of applications come

forward."

Mr. BLAND thought there could be no impropriety in referring any subject to a committee, but surely this deserved the serious and solemn consideration of Congress. He hoped no gentleman would oppose the compliment of referring it to a Committee of the whole; beside, it would be a guide to the deliberations of the committee on the subject of amendments, which would shortly come before the House."

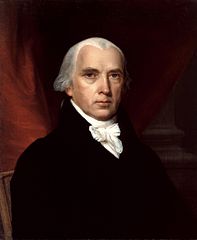

Mr.

MADISON [James Madison, delegate Federal Convention of 1787; member House

of Representatives (VA) 1789-97; Fourth President of the United

States (1809-17)] said, he had no doubt but the House was inclined to

treat the present application with respect, but he doubted the

propriety of committing it, because it would seem to imply that the

House had a right to deliberate upon the subject. This he believed was

not the case until two-thirds of the State legislatures concurred in

such application, and then it is out of the power of Congress to

decline complying, the words of the Constitution being express and

positive relative to the agency Congress may

have in case of applications of this nature. "The Congress, whenever

two-thirds of both Houses shall deem it necessary, shall propose

amendments to this Constitution; or, on the application of the

Legislatures of two-thirds of the several States,

shall call convention for proposing amendments." From hence it must

appear, that Congress have no deliberative power on this occasion. The

most respectful and constitutional mode of performing our duty will be,

to let it entered on the minutes, and remain upon the files of the

House until similar applications come to hand from two-thirds of the

States.

Mr.

MADISON [James Madison, delegate Federal Convention of 1787; member House

of Representatives (VA) 1789-97; Fourth President of the United

States (1809-17)] said, he had no doubt but the House was inclined to

treat the present application with respect, but he doubted the

propriety of committing it, because it would seem to imply that the

House had a right to deliberate upon the subject. This he believed was

not the case until two-thirds of the State legislatures concurred in

such application, and then it is out of the power of Congress to

decline complying, the words of the Constitution being express and

positive relative to the agency Congress may

have in case of applications of this nature. "The Congress, whenever

two-thirds of both Houses shall deem it necessary, shall propose

amendments to this Constitution; or, on the application of the

Legislatures of two-thirds of the several States,

shall call convention for proposing amendments." From hence it must

appear, that Congress have no deliberative power on this occasion. The

most respectful and constitutional mode of performing our duty will be,

to let it entered on the minutes, and remain upon the files of the

House until similar applications come to hand from two-thirds of the

States. Mr.

BOUDINOT hoped the gentleman who desired the commitment of the

application would not suppose him wanting in respect to the State of

Virginia. He entertained the most profound respect for her--but it was

on a principle of respect to order and propriety that he opposed the

commitment; enough had been said to convince gentlemen that it was

improper to commit--for what purpose can it be done? what can the

committee report? The application is to call a new convention. Now, in

this case, there is nothing left for us to do, but call one when

two-thirds of the State Legislatures apply for that purpose. He hoped

the gentleman would withdraw his motion for commitment.

Mr.

BOUDINOT hoped the gentleman who desired the commitment of the

application would not suppose him wanting in respect to the State of

Virginia. He entertained the most profound respect for her--but it was

on a principle of respect to order and propriety that he opposed the

commitment; enough had been said to convince gentlemen that it was

improper to commit--for what purpose can it be done? what can the

committee report? The application is to call a new convention. Now, in

this case, there is nothing left for us to do, but call one when

two-thirds of the State Legislatures apply for that purpose. He hoped

the gentleman would withdraw his motion for commitment.

Mr. BLAND.--The application now before the committee contains a number of reasons why it is necessary to call a convention. By the fifth article of the Constitution, Congress are obligated to order this convention when two-thirds of the Legislatures apply for it; but how can these reasons be properly weighed, unless it be done in committee? Therefore, I hope the House will agree to refer it.

Mr. HUNTINGTON [Benjamin Huntington, member House of Representatives (CT) 1789-91] thought it proper to let the application remain on the table, it can be called up with others when enough are presented to make two-thirds of the whole States. There would an evident impropriety in committing, because it would argue a right in the House to deliberate, and, consequently, a power to procrastinate the measure applied for.

Mr. TUCKER [Thomas Tudor Tucker, member House of Representatives (SC) 1789-93; Treasurer of the United States, 1801-28] thought it not right to disregard the application of any State, and inferred, that the House had a right to consider every application that was made; if two-thirds had not applied, the subject might be taken into consideration, but if two-thirds had applied, it precluded deliberation on the part of the House. He hoped the present application would be properly noticed.

Mr.

GERRY,--[Elbridge Gerry, delegate Federal Convention of 1787; member House of Representatives (MA) 1789-93; Governor of

Massachusetts 1810-12; Vice President of the United States (1813-14)]

The gentleman from Virginia (Mr. Madison) told us yesterday, that he

meant to move the consideration of amendments on the fourth Monday of

this month [May 25, 1789]; he did not make such motion then, and may be

prevented by accident, or some other cause, from carrying his intention

into execution when the time he mentioned shall arrive. I think the

subject however is introduced to the House, and, perhaps, it may

consist with order to let the present application lie on the table until

the business is taken up generally.

Mr.

GERRY,--[Elbridge Gerry, delegate Federal Convention of 1787; member House of Representatives (MA) 1789-93; Governor of

Massachusetts 1810-12; Vice President of the United States (1813-14)]

The gentleman from Virginia (Mr. Madison) told us yesterday, that he

meant to move the consideration of amendments on the fourth Monday of

this month [May 25, 1789]; he did not make such motion then, and may be

prevented by accident, or some other cause, from carrying his intention

into execution when the time he mentioned shall arrive. I think the

subject however is introduced to the House, and, perhaps, it may

consist with order to let the present application lie on the table until

the business is taken up generally.

Mr. PAGE [John Page, member House of Representatives (VA) 1789-97; Governor of Virginia 1802-05] thought it the best way to enter the application at large upon the Journals, and do the same by all that came in, until sufficient were made to obtain their object, and let the original be deposited in the archives of Congress. He deemed this the proper mode of disposing of it, and what is in itself proper can never be construed into disrespect.

Mr. BLAND acquiesced in this disposal of the application. Whereupon, it was ordered to be entered at length on the Journals, and the original to be placed on the files of Congress."

*****

Summation

The May 5, 1789 discussion reveals several key points about Congress' understanding of the application/call process of Article V:

- A convention call is based on a numeric count of applying states rather than the subject matter of the application.

- The object of the application is to cause a convention call. States apply for a convention not an amendment.

- Congress has no authority to deliberate on a convention call meaning no committee, debate or vote is permitted.

- No congressional committee may "consider" application contents and decide whether to call a convention on the basis of that content.

- Applications "lie on the table...until sufficient were made to obtain their object."

The House (and later the Senate) rejected Bland's motion. The House decided no application should be submitted to a committee for its "consideration." This would imply Congress had authority "deliberate" on the matter and thus Congress could refuse to call a convention ("procrastinate the measure applied for"). Instead under the rules of the House (later adopted by the Senate) all applications for an Article V Convention "lie on the table" meaning the application remains in force "until sufficient were made to obtain their object" [a convention call]. When this occurs Congress must call a convention. Thus there is no committee, debate or vote on whether Congress will call a convention.

The phrase "lie on the table until sufficient were made to obtain their object" is recognition of the fact a convention call is a continuing obligation of Congress transcending the usual parliamentary procedure of matters placed before Congress which "lie on the table." Under parliamentary rules of Congress if something "lies on the table" it remains in effect until acted upon but dies on adjournment of Congress at the end of its session. The matter must be then resubmitted to a new session of Congress. Some convention opponents have argued the term of effect for an application is only for the session of Congress in which the application is submitted. Therefore, unless the states submit the necessary two thirds applications within a single session of Congress, the applications no longer have effect when Congress adjourns. The comments of May 5, 1787 however make it clear Article V applications ("applications of this nature") are an exception to this parliamentary rule on which Congress has no deliberative power.

The Founders were fully aware Congress would meet in sessions. They specified in the Constitution members of Congress have terms of office. They specified a date each year when Congress would meet. From their own experience in state legislatures they knew it was common practice for each meeting of a legislature in a new year to be called a new session or term of the legislature. However the obligation to call a convention is a continuing obligation on all sessions of Congress and therefore transcends any particular session of Congress. If this were not the case, the call would not be "peremptory" as described by Hamilton. Congress would simply let its session expire and thus terminate the obligation to call a convention even if the states somehow met this standard by simply adjourning before issuing a call. Moreover adjournment in Congress requires consent by both houses meaning a vote. This vote is a form of "deliberation" on whether to call a convention and as described in May, 1787, not permitted. Thus regardless of whatever session applications are submitted, Congress is bound to call a convention when the applications show two thirds of the states applied.

All applications therefore have full effect regardless of date of submission. All applications share the same constitutional "subject" or "object": to cause a convention call. "On the application of ...two thirds...Congress shall call" thus refers to the applications by two thirds of the state legislatures becoming a single application for a convention call ("until two-thirds of the State legislatures concurred in such application"). Once this composite application accomplishes its constitutional object it is considered discharged. The composite application cannot be used by Congress again to cause a convention call because of the terms of Article V ("shall call a convention for proposing amendments" not conventions).

Thus Congress is required to call a convention each time a set of applications ("on the application) constitutes applications by two thirds of the several state legislatures. As the basis of determination is numeric count rather than amendment subject the composite can be comprised of any number of amendment subjects provided each set has only one application from each state creating that particular composite. Only when all composite sets of applications which create two thirds application by the states are discharged (presently 11 sets) is Congress is no longer obligated to call a convention based on that composite set until the states submit a new set of applications creating a new composite.

This explains why Congress, until 2015, used the only unconstitutional option open to them to not call a convention. They simply refused to count the applications by burying them in the congressional archives. Despite this it was a well known fact the states had submitted "hundreds of applications" for a convention call. Politically Congress opposed obeying the Constitution as demonstrated by its continual opposition in federal court to lawsuits mandating it do so. Therefore Congress made no effort to correct the public perception (aided by the efforts of JBS/Eagle Forum and an inept misinformed mass media) that the applications on record were insufficient to cause a convention call. However all this fell apart when FOAVC, starting in 2007, began publishing the actual public record of the applications and other associated public record (such as the discussion of May 5, 1787) on the Internet for all to examine. By 2015 the effect of this published public record was so strong even Congress could no longer ignore it.

Congress provided no means of retrieval or notification by the congressional archives to notify it when the states had applied in sufficient number to warrant the convention call. In other words, no mechanism was provided to take the applications "off the table" when required. The fault for this lies with those in Congress in May, 1787 who should have, but did not, establish such a mechanism for taking applications "off the table" when required by the terms of Article V. A simple rule in the House (and later the Senate) phrased such that it became a permanent rule of Congress by noting in the rule it was mandated by constitutional provision and thus was a continual permanent rule just like the applications themselves would have sufficed. However Madison and the others failed to do this probably because it never occurred to them Congress would deliberately violate the Constitution in order to further their own political power. However Congress is now counting the applications in its first serious attempt to rectify what has to be the most serious constitutional violation by the Government in United States history.

Madison's comments (and others) make it is clear Congress has no "deliberative" power on a convention call. Thus, Congress can neither debate nor vote on a convention call eliminating most of the usual processes of passage through Congress. The exception is "unanimous consent." In unanimous consent, Congress creates a call with the foregone conclusion, because the Constitution demands it, that all membership agrees with the call thus eliminating any debate or vote. A convention call sets a time and location for the convention. This issue of time and place could be debated in Congress. However if convention opponents in Congress attempted to use this tiny window of discretion to prevent a convention call by endlessly arguing the time and place the states would have every right to hold a convention without a congressional call as they did in September, 2016.

While not called "same subject" (the term later popularized by JBS/Eagle Forum in their anti-convention campaign) the principle of "same subject" was considered by Congress at the earliest possible moment (submission of the first state application to Congress in 1789) and rejected. As stated by Congressman Huntington, "because it would argue a right in the House to deliberate, and, consequently, a power to procrastinate the measure applied for." Thus the public record proves emphatically a convention call is based on a numeric count of applying states rather than by amendment subject within an application. The public record proves no application may be "considered" by a congressional committee.

The public record proves Congress has no power of deliberation or vote on a convention call. The public record proves applications transcend congressional sessions and remain an ongoing obligation of Congress meaning all applications regardless of date of submission remain in full effect until they accomplish "the object" of causing a convention call. The public record proves applications are arranged in sets of two thirds applications by the state legislatures and the composite set becomes a single application on which Congress must call a convention. The public record proves a composite set of applications can only be used once to cause a convention call.

Page Last Updated: 9-APRIL 2017